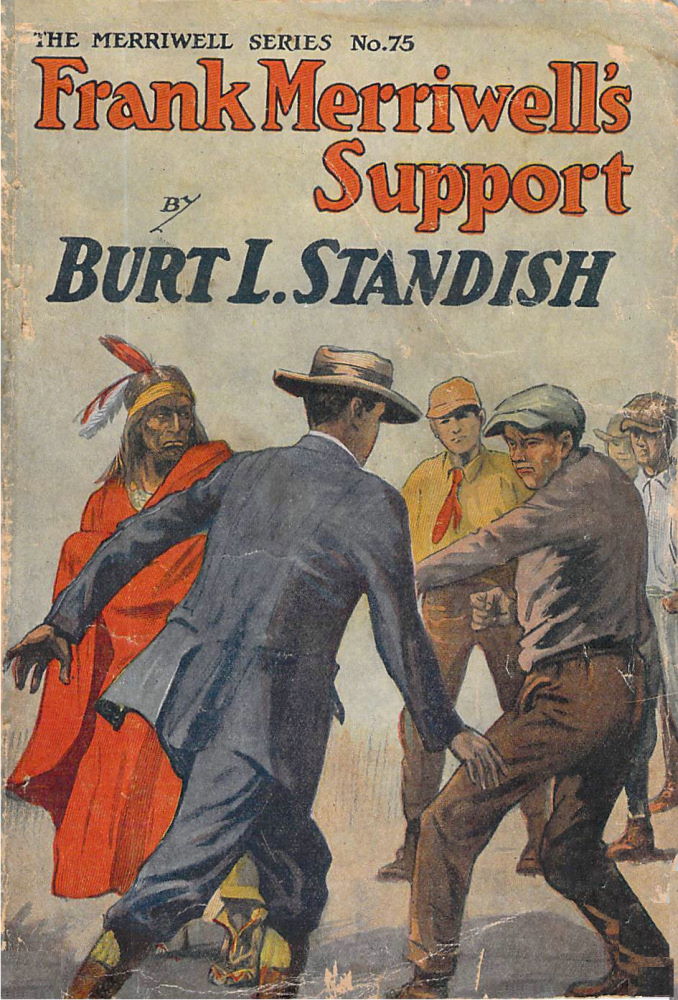

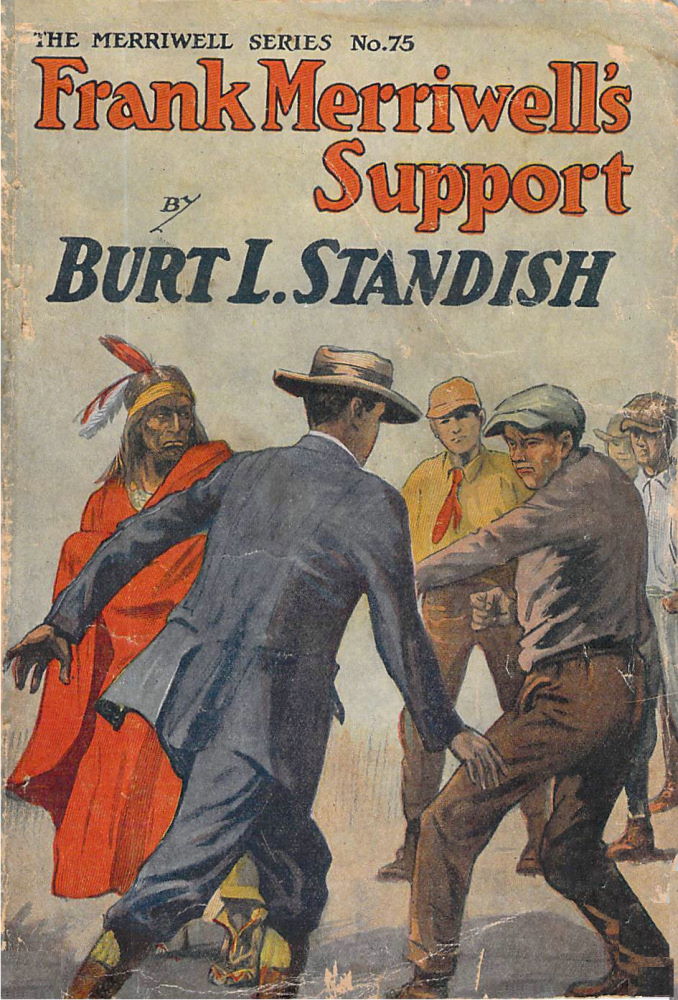

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Frank Merriwell's Support, by Burt L. Standish

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Frank Merriwell's Support

A Triple Play

Author: Burt L. Standish

Release Date: July 21, 2020 [EBook #62719]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FRANK MERRIWELL'S SUPPORT ***

Produced by David Edwards, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

BY

BURT L. STANDISH

Author of the famous Merriwell Stories.

STREET & SMITH CORPORATION

PUBLISHERS

79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York

Copyright, 1901

By STREET & SMITH

Frank Merriwell’s Support

(Printed in the United States of America)

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages, including the Scandinavian.

It was the seventh inning, Frank Merriwell’s team had not scored, while the Omaha Stars, who had been putting up a hard game against the boys from the East, had made two runs, one in the first inning and one in the fifth.

Frank had been pitching a fine game, although his wrist, sprained some time before, had not permitted him to use the double-shoot. In the seventh inning, with the very first ball he pitched, he gave his wrist a twist that sent a shooting pain all the way to his shoulder.

The ball went wide of the plate, and the batter did not strike at it. When Bart Hodge returned the ball, he knew something had happened, by the expression on Frank’s face. Merry caught the ball with his left hand and stood still, holding it.

“Play ball!” roared the excited crowd. “Make him pitch!”

Still Frank seemed in no hurry. He took the ball[6] in his hand, while Bart gave the signal for a drop. Merry shook his head, and Bart signed for an out. Again Frank shook his head, assuming a position that told the entire team he intended to use a high, straight ball. But he did not pitch.

Dorrity, the captain and first-baseman of the Stars, demanded of the umpire that Merriwell be compelled to deliver the ball.

“Pitch the ball!” roared the crowd.

Even that did not seem to incite Frank to put it over.

“Two balls!” called the umpire, although Frank had not again delivered the sphere to the bat.

“Ha!” shouted the crowd. “That’s the stuff!”

The second ball had been called on Merry as a penalty for delaying the game for no good reason.

A grim look came into the face of the greatest pitcher ever graduated from Yale. He did not kick at the decision of the umpire, nor did he show great haste in pitching after this.

“Call another!” cried several of the spectators. “He’s in a hole, and he knows it!”

Frank settled himself firmly on the ground, just as Bart was ready to start down to ask what was the matter. Then he sent over a high, straight one that would have been a ball had the batter let it alone.

But the batter hit it. The man with the stick happened to be Hanson, the heavy hitter of the Stars, and he tapped the ball a terrible crack.

Away sailed the sphere, going out on a line over the infield, and Hanson’s legs took him flying down to first.

Both Swiftwing and Gamp went after the ball, but Frank saw at once that neither of them could catch it.

Swiftwing was a great runner, and he sped to cut the ball off after it struck the ground.

Hanson crossed first and tore along to second, urged by the roaring crowd.

Bart Hodge groaned as he saw the ball strike the ground and go bounding away into left field, with Swiftwing tearing after it.

“Home run! home run!” yelled the spectators, while one of the home team raced down to third, to be on hand there and send Hanson home as he came along.

Away out in the far extreme of left field Swiftwing finally ran down the ball. But Hanson was almost to third, and the spectators in the grand stand and on the bleachers were certain he could reach home before the ball could be sent in.

“Come home! come home!” they screamed.

Hanson crossed third, and the coacher sent him right along.

In the meantime Swiftwing had picked up the ball and given it a quick snap to Gamp, the long New Hampshire youth, who was within two rods of him. Joe turned with the ball in his hand, and saw Hanson crossing third.

Then Joe set his teeth and swung back the hand that held the ball. The crowd expected he would throw to Rattleton, on second. At first it seemed that he had thrown to second, but had failed to get the range correctly.

Then it was seen that Gamp had tried the seemingly impossible task of throwing to the plate to cut the runner off.

“Run, Hanson—run!” shouted the spectators.

Hanson was doing his best to beat the ball to the plate, but that ball came on with amazing speed. It was almost a “line throw” from the far outfield, and the crowd was amazed by the manner in which the ball hung up in the air instead of dropping to the ground. It showed what wonderful force had been put into the throw.

Hodge settled himself in position to take the ball, and suddenly, as Hanson neared the plate, the coachers shrieked for him to slide.

Hanson slid headlong, but Bart caught the ball and “bored” it into his back, actually pinning him to the ground while his hand was yet a foot from the plate. He tried to squirm forward and reach the plate, but the voice of the umpire called:

“Out!”

A hush fell on the witnesses of this amazing piece of work. Only a moment before they had been roar[9]ing loudly, but, of a sudden, they were silent. Then somebody with a hoarse voice roared:

“Well, what do you think of that for a throw! Talk about a wing—that fellow’s got it!”

Somebody clapped his hands, and a general volley of applause followed.

Hanson was filled with chagrin, for he had felt confident of making a home run. He turned and quarreled with the coacher who sent him home from third, and would not believe the ball had been thrown all the distance from the farthest outfield to the plate.

Jack, the second-baseman of the Stars, now took his place to strike.

Merriwell had been rubbing his wrist as he walked down into the box, after backing Hodge up on the catch of Gamp’s throw, and the expression on his face, had any one studied it, seemed to indicate a troubled mind.

“If Dick were here,” he muttered, thinking of his young brother, “we’d be all right.”

But Dick Merriwell was not there, having been left behind in Wyoming, to remain at the side of Old Joe Crowfoot, who had been shot and severely wounded.

Despite his youth, Frank’s brother had shown himself a perfect little wizard as a pitcher, being able to hold down heavy hitters. Just now he would be handy to step into the box in Frank’s place, but he was far away.

And there was no other pitcher on the team able to hold down the heavy hitters of the Stars. So Frank set his teeth and resolved to pitch the game through to the best of his ability.

Jack was a good hitter, but, up to this time, he had been unable to touch Merriwell for a safe one. Frank tried a high one, which the latter let pass. An out followed, and another ball was called.

Then Merry tried a drop, but again he felt that shooting pain, and the ball went wide.

Now Frank was forced to put the ball over, in order to prevent the batter from walking to first. He used speed, and kept it shoulder high, with a slight in shoot.

Jack stepped forward and met the ball fairly, driving it out on a line.

Carson jumped for the ball, touched it with his fingers, but did not stop it. Jack reached first and started for second, but Rattleton got the ball, and Carson covered second in time to drive the runner back to first.

Maloney, the next hitter, was tall, red-headed, and freckle-faced. He rapped the very first ball that Frank pitched, sending it down to Rattleton so hotly that Harry fumbled, and the hitter was able to reach first ahead of the throw.

“Everybody hits!” cried Dorrity, who was near[11] third. “Get against it, Corrigan, old man! Drive it out hard!”

Corrigan looked confident, but Frank caused him to fan at the first ball delivered. Then Merry tried to work the corners, but found himself rather wild, and three balls were called.

“Now he’s got to put ’em over!” cried Dorrity. “Wait it out!”

Frank took a chance and sent a straight one over.

Corrigan did not wait, but nailed the ball hard. It went to Ready with the speed of a bullet. Ready put his body in front of the ball, which took a nasty bound and struck him fairly between the eyes, knocking him over.

Ready was dazed, and by the time he had recovered and got the ball, Jack was on third and Maloney on second. Ready caught up the ball and swung his arm to throw to first.

Frank saw that the throw would be useless, as Corrigan was already too near the bag, and he shouted for Ready to hold the ball.

Ready could not stop the swing of his arm, but he held on to the ball long enough to throw it down at his feet, and it bounded merrily away.

“Score!” yelled a coacher, and Jack made a jump off third to go home.

The spectators rose up and whooped madly once more.

Frank made a leap and got in front of the ball, which he succeeded in stopping. Fortunately for him, Jack saw this soon enough to dive back to third.

Merry recovered and drew back his hand to throw to third, but instantly decided that it would be useless, knowing that a team often goes to pieces and loses a game in a single inning by getting to throwing the ball round in a hasty and reckless manner, so he held the sphere.

But the bases were full and but one man was out. Something told Frank that he was in a bad box. Still, he set his teeth and resolved to “pull out” if it were possible.

The coachers were talking from both sides of the diamond, and the excited crowd had not stopped its roaring.

Hodge was pale, and there was a fierce gleam in his eyes.

“Now we’ll hold ’em! Now we’ll hold ’em!” cried Rattleton, from second.

“Talk about your stars!” exclaimed Ready. “I saw a few that time!”

“They won’t get another hit, Merry,” assured Carson, who was playing short.

“Put ’em right over,” advised Browning.

“All a dud-dud-dinged accident!” asserted Gamp, from distant center garden.

Swiftwing and Carker were the only silent ones[13] behind Merry, for even Hodge grimly asserted that it was all right.

Then Merriwell resolved to use the double-shoot, if it broke his wrist. Bart called for an out curve as Dorrity stepped up to the plate; but Merry assumed a position that told everybody on the team he meant to use the famous reverse curve, which he alone could command and control.

Bart knew Merry was desperate, for Frank had told him he would not resort to that extreme in the game.

Dorrity was cool enough, but the first ball seemed just what he desired, and he bit at it. The reverse curve fooled him nicely, and he did not touch the ball.

“One strike!” declared the umpire.

Bart smiled grimly and nodded for another. Frank used exactly the same sort of a curve, and again Dorrity went after it and failed to connect.

“Why, it’s easy! it’s easy!” said Bart.

“A perfect snap,” assured Carson.

“Couldn’t hit one of them in fourteen million years,” said Ready.

“He’ll think he’s got the jam-jims—I mean the jim-jams,” came from Rattleton.

“Please let him hit it,” urged Browning. “I want another put-out in this inning. He can’t hit it out of the diamond.”

But Merry did not let up in the least. The very next one was a speed ball, but Frank caused the curves to reverse the other way, and Dorrity let it pass.

“Batter is out!” announced the umpire.

Dorrity threw down his bat and started into the diamond, yelling:

“What’s that? That ball didn’t come within a foot of the plate!”

“Sit down!” commanded the umpire grimly.

Dorrity insisted on kicking, and the umpire warned him again in a manner that meant business.

“Robbery!” muttered the captain of the Stars, as he walked back to the bench.

Two were out, and Batch, the pitcher of the home team, was the next hitter. It happened that Merry had discovered Batch’s weak point, and he did not fear him, for which reason he did not again use the double-shoot in that inning.

A sharp drop caught Batch the first time. Then followed one close to the batter’s hands, and he hit it on the handle of the bat. The ball rolled out to Frank, who threw Batch out at first while Jack was racing home.

The home team had not scored in that inning, but they were still two ahead of the visitors, who had failed to make a single tally.

Hodge met Frank as he came in.

“How is the wrist?” asked Bart anxiously.

“Bad,” confessed Merry; “but don’t you say a word about it.”

“What made you use the double?”

“Had to do something to get out of that hole.”

“But——”

“It’s all right. We’re going to win this game—if we can.”

“It will take some scores to do it, and the weak end comes up this time. We’ve got only one more chance after this.”

Swiftwing was the first batter. As a rule, the Indian hit well, but had not secured a safe one thus far in the game. The former Carlisle man now seized a bat and advanced to the plate, his manner betraying determination to do something. Frank spoke to him, saying:

“Don’t try to kill the ball, John. A single is good enough, if you can’t get a bag on balls. But wait—wait.”

Merry had found the Indian a poor waiter, and this case was no exception. John was so eager to get a hit that he fell an easy victim to the artifices of Batch, finally popping up a little fly, which was taken by the third-baseman of the Stars.

Rattleton’s heart was in his boots when he advanced to the plate, but he pretended to brace up. Batch worked the corners, and Harry bit at two bad[16] ones. Then, in sheer despair, Rattleton slashed at a high one that was over his head, and hit it!

The ball was driven on a line between short and second, and Harry raced down to first. If he had been contented with that, all would have been well; but he tried to stretch a single into a two-bagger, and O’Grady, the left-fielder, who had secured the ball, threw to second.

When it was too late, Harry saw he could not reach second, and he tried to turn back. Then he was caught between bases.

“That’s what loses the game!” groaned Hodge, as he saw the opposing players get on the base-line to run Rattleton down.

Rattleton did his best to escape, while the players skilfully forced him back toward first, and then pinned him so that he could not dodge them. He was tagged with the ball, and the second man was out.

The crowd was delighted. They had expected a hot game, and they were getting their money’s worth.

Frank’s team had been well advertised in Omaha, the papers telling of its successful career through the Rocky Mountain region. Thus far not a single defeat had been chalked against the Merries; but now it began to seem that the long string of victories would be broken.

“La! la!” sighed Jack Ready. “How foolish it is for a man to try to do more than he is capable of accomplishing!”

Then he pretended to wipe a tear from his eye as Rattleton, looking very cheap and disgusted, came in to the bench.

“Somebody please kick me!” mumbled Harry.

“With great satisfaction!” exclaimed Jack, and he proceeded to do so.

“Thanks!” murmured Rattleton, as he sat down.

Frank said nothing to Harry, for he knew the unlucky chap felt bad enough about what he had done, and Merry had learned by experience that it did little good with a young team to “call down” the players or “chew the rag” with them on the field.

Old stagers will take a call-down, but it takes the spirit out of youngsters, sometimes making them sullen and sulky. A young ball-player needs encouragement at all times, criticism often, but public call-downs never. The captain or manager who is continually yelling at his players on the field and telling them how bad they are doing, causes them to lose five games where he drives them to win one.

Carker was the next man up, and Frank admonished him to wait for the good ones. Greg was beaten already, and his appearance showed it. Batch was full of confidence, and he put the balls right over.

Some batters have a faculty of working a pitcher,[18] often getting first base on balls; but the fellow who does this is usually a good hitter, or he stands up to the plate, as if he was anxious to “line it out.” When a pitcher is satisfied that the batter is longing to hit he gets wary and declines to put the ball over. On the other hand, let the pitcher suspect the batter is trying to get a base on balls, and he does his best to “cut the plate.”

The first two balls pitched were strikes, yet Carker swung at neither of them.

“It’s all off!” growled Hodge. “He’s the third victim.”

Then Batch sent in a wide one, and, knowing there were two strikes on him, Greg reached for it.

Somehow Carker caught that ball on the end of his bat and sent it skipping down past the first-baseman, who made an ineffectual effort to block it.

“Run!” yelled Ready, suddenly rousing up. “Dig, you duffer! It’s a hit!”

Carker had been amazed by his own success, but he came out of his “trance” in a moment and hustled down to first. Gamp was there, and he made Carker stick to the bag.

Merriwell grasped a bat and stepped up to the plate. Batch was afraid of Merry, for he knew Frank was a good hitter, and he started in to try to “pull” the batter.

Apparently Frank was ready and anxious to “lace”[19] the first good one, but his judgment seemed good, as he let the first two pass, and both were called balls.

Batch was holding Carker close to first. As Hanson, the catcher of the Stars, was a good thrower, there seemed little chance for Greg to steal second.

The third ball was pretty high, and Merry took a chance on it by failing to swing. A strike was called. Frank simply shook his head, thus expressing his belief that the decision was not correct.

The next ball was a drop, and it seemed too low, so Merry let that pass. Another ball was called.

“Got him!” chirped Ready. “Oh, ye Grecian gods! smile upon us now. Be quiet, my good people, and watch us turn the trick. We are due to do it.”

Batch settled himself for business, and whistled a speedy one to go straight over the rubber. It didn’t get over, however, for Frank met it “on the nose.”

At the crack of the bat, as it seemed, Merry started to run. The ball went out on a line toward right field, and Carker dashed for second. The right-fielder made a jump to get in front of the ball, but it went past him and struck the ground ten feet beyond.

Away into right field bounded the ball, while Carker and Merry tore round the bases. As Carker approached third, he saw Carson wildly motioning for him to go home.

Greg did not look round, but, had he done so, he would have seen Merry coming after him with the speed of the wind. Frank was overhauling Greg in a most amazing manner.

Under ordinary circumstances, the hit into right field would have been a fair three-bagger; but Merry covered ground so fast that Carson took a chance in sending him home.

As Carker approached the plate, Frank Merriwell was not twenty feet behind him. The fielder had secured the ball and thrown it to the first-baseman, who ran out to take it.

Then the baseman whirled and lined the ball to the plate.

Carker did not slide, but he barely went over the plate ahead of the ball. Frank, however, threw himself forward in a long headlong slide.

Hanson took the ball and touched Merry, but Frank was lying with his hand on the plate.

“Safe!” declared the umpire.

Frank had stretched a three-bagger into a home run, and the score was tied.

Of a sudden, a great change had come over the game.

“It’s all over, boys!” laughed Ready. “We can’t help winning now! It’s another scalp for us!”

“That’s Frank Merriwell!” cried an excited boy on the bleachers. “You can’t beat him! The whole world can’t beat him!”

Batch was sore. A short time before he had been smiling, but now there was no smile on his face. He looked serious enough as Ready came up. Jack was determined to “keep the ball rolling,” and he got a nice hit off the second ball pitched.

Among the spectators were two men who were watching the game with deep interest. One man was stout and red-faced, with a stubby mustache, while the other was slender and dark, wearing a suit of blue. The stout man choked and gurgled when the umpire declared Merry safe at the plate.

“Rotten!” he snarled. “He was out by a foot!”

“I don’t think so, Hazen,” said the other man.

“Why, what ails you?” gurgled the portly man. “Do you want to see us lose this game, Wescott?”

“Not much,” answered Wescott. “It means something to me. I have over two hundred dollars bet on the Stars.”

“Two hundred!” exploded Hazen. “I have almost a thousand! I spent half of last night hunting bets, and I took everything I could get at any odds.”

“Well,” said the man in blue, “I’m afraid we’re in a bad box. This fellow Merriwell is lucky. He has a way of winning at anything and everything.”

“But those kids can’t beat our boys!”

“They may. The score is tied.”

“How in blazes can you take it so easy?”

“What’s the use to fret? It won’t win the game.”

“Fret! fret! If you had staked as much as I have, you’d not be so cool.”

“You can afford to lose a thousand as well as I can two hundred. You made three thousand on the Ryan-Cummings fight.”

“That was a sure thing. I was tipped off the way that mill was going.”

“And you thought this a sure thing to-day?”

“Yes. Why not? Those chaps are a lot of boys. The Stars are veterans.”

“But that lot of boys have the best man for a cap[23]tain who stands in shoe-leather to-day. He makes them win games—when he can’t win them alone.”

“He can’t make them win all the time.”

“He does. He hasn’t been pitching at his usual standard to-day. He had to open up in the last inning, and he will in the next. See if he doesn’t shut the Stars out.”

Carson was in position to strike. Batch tried all the tricks he knew, but Berlin waited till three balls had been called.

Then a sign passed between Jack and Berlin for the former to go down on the next ball pitched.

The ball was right over, and Carson swung at it, missing intentionally. At the same time he seemed to lose his footing and fall back against the catcher. The trick was done so well that Carson’s own friends did not know it was intentional, and he bothered the catcher long enough for Ready to reach second safely ahead of the throw to catch him.

Carson did not lose his head, but he was patient, which resulted in a base on balls.

Bart Hodge advanced to the plate.

“It’s all over!” cried Ready, as he danced about close to second. “He’ll hit it a mile!”

Batch caught Bart on a drop at the very start, Hodge missing the ball by several inches.

“Get under it!” called Ready. “If you let him strike you out, I’ll drop dead right here.”

The next one was a ball, but Bart hit the third one, making a clean single, on which Ready scored from second. Merriwell’s team had the lead for the first time during the game.

“You’ve lost your money, Hazen,” said Wescott.

But Hazen had suddenly started from the bleachers, jumped over the rail, and was moving toward the bench occupied by the visitors.

“What the dickens is he up to?” muttered Wescott, in surprise.

Frank felt a hand touch his arm, and, looking round, found the red-faced man at his elbow.

“Fifty dollars if you let them hit you in the next inning!” breathed Hazen huskily. “Throw the game and the money is yours!”

Merry felt his face turn red.

“What are you doing here?” he demanded.

“Will you do it?” panted Hazen.

“Where is an officer?” demanded Frank. “I want this man put out.”

“A hundred dollars!” came from the gambler.

“Get out!” Frank sternly commanded. “You can’t buy me!”

“Two hundred!” bid Hazen. “Don’t be a fool! I am good for it! Here! Shake hands with me!”

He suddenly grasped Frank’s hand, into which he pressed something. When Merry looked, he was as[25]tonished to see the man had left a wad of bills in his hand.

Instantly Frank flung the money in the man’s face, speaking in a low, hard tone:

“You’ve made a big mistake! Take your dirty money and get out of this lively!”

Hazen’s face became redder than ever. Seeing he was exposed, he immediately said:

“I want you to stand by your word! You said you’d sell the game for two hundred dollars if you got ahead; now you can’t back out, for I hold you to the agreement.”

Merry saw through the trick, and he turned pale, while a strange laugh broke from his lips.

“You’re a big bluffer, but I don’t think you’ll fool anybody. It will take more than two hundred dollars to buy me.”

The man had picked up his money.

“Then you’re a liar!” he said; “for you made a fair and square agreement with me.”

“You are the one who lies!” Merry asserted. “I never saw you before.”

“You’re a cheap chap to go back on your word.”

This was something more than Frank could stand, and he had the stout man by the collar in a moment.

“Swallow your words!” he said, as he gave the man a shake. “Take them back!”

“Never! It’s true!”

Then Frank Merriwell gave that corpulent party such a shaking that it took the wind out of Hazen and made him limp as a rag.

“Sus-sus-stop it!” he spluttered. “How dare you lay hands on me?”

“How dare you offer me money to throw this game!” exclaimed Merry indignantly. “What you need is a first-class thrashing!”

“That’s the stuff!” roared the crowd. “Give it to him, Merriwell!”

An officer appeared, and Hazen was ordered back to the bleachers. He retired, his face purple with anger, while he muttered beneath his breath.

This little incident seemed to turn the sympathy of a great portion of the audience toward Merriwell. Somebody shouted:

“What’s the matter with Frank Merriwell?”

The crowd thundered:

“He’s all right!”

“Play ball!” called the umpire impatiently.

Hazen resumed his seat beside Wescott, who said:

“Well, you made an exhibition of yourself! What good did it do you?”

“That fellow is a fool!” growled the stout man.

“You might have known you could not buy him.”

“Every man has his price.”

“Not Frank Merriwell.”

“Oh, I don’t believe he is an exception.”

“You found him so.”

“I didn’t offer him enough.”

“Why didn’t you?”

“Because there is another way to get this game.”

“How?”

“I know Derring, the umpire.”

“Well?”

“He has seen me.”

“What of that?”

“He’s looking this way now.”

Then Hazen suddenly held up his hand and made a peculiar sign. It was impossible to tell whether Derring saw and understood or not.

“What are you doing?” asked Wescott.

“Making my last bid for this game,” declared the corpulent man.

“Well, you must have nerve!” exclaimed Wescott. “That fellow can’t throw the game now.”

“Perhaps not; but we’ll see. Look at that. Ha!”

Gamp was the batter, and at this juncture the umpire called a strike on him that was over his head.

“Do you think he did that intentionally?” whispered Wescott, as the crowd roared in derision.

“Wait,” was the only thing Hazen would say.

The next ball was wide of the plate, but again a strike was called by the umpire.

“Sus-sus-sus-say!” stuttered Joe, “dud-dud-dud-don’t[28] you want me to lend ye a pup-pup-pup-pair of glasses?”

The next ball was so low that the catcher almost picked it up off the ground, but the umpire loudly announced:

“Batter is out!”

“Rank!” howled a voice.

“Bum!” yelled another.

“Awful! awful!” shrieked a shrill-voiced man.

Then the crowd took it up and jeered at the umpire.

“By George!” exclaimed Wescott, laughing, “I believe the fellow has taken you at your offer, Hazen!”

The corpulent gambler drew a breath of relief.

“I hope he has,” he said. “There’s a bare show that the Stars will win out.”

Gamp made the third one out, and the home team came in from the field.

Merry went out and protested to the umpire, but his protest did no good.

“We’ll have to hold them down, fellows,” said Frank. “It’s the only way to win out.”

His arm, however, was feeling bad, and he was fearful that he might find great trouble in remaining in the box to the end.

Teller headed the list for the home team, and he was the first man up. Frank gave him the first one right over the heart of the plate.

“One ball!” said the umpire.

Frank looked at the man.

“Did I understand you?” he asked. “Did you call that a ball?”

“Don’t get fresh, young man!” growled the umpire. “You know it was a ball!”

“Didn’t it go straight over the heart of the plate?”

“It was a ball! I called it that, and it has to stand.”

The crowd showed its disgust by uttering cries of derision, and shouting scornfully at the umpire. Merry put another over, but this time he used a drop.

“Two balls!”

“Outrage!” snarled Hodge. “Hit him, Merry!”

Teller realized that something had happened, and he refused to strike at either of the next two pitched, though both were on the outside corner. The umpire sent him to first.

Then came Skew, who swung at the ball as Teller went down to second for a steal.

For once, Hodge threw a bit wild, but Rattleton got the ball and jumped for the man, who slid. Teller was tagged while two feet off the base.

“Safe at second!” said the umpire.

“What is this?” yelled a man on the bleachers. “We came here to see a game of ball. This is a regular roast!”

The work of the umpire was turning the crowd against the home team.

Skew hit the next ball pitched. It went straight at Ready, who gathered it up and saw it would be an easy thing to catch the runner with a good throw. Jack sent the ball whistling across the diamond, and Browning had it three seconds before the runner passed over first.

“Safe!” cried the umpire.

Frank tried to convince the umpire that the decision was wrong, but found he was wasting his breath in talk.

O’Grady came up. Thinking he might wait to get his base on balls, Merry ventured one on the corner.

O’Grady hit it hard.

“That ties the score!” cried many.

The ball went out to Swiftwing, who was compelled to run hard, coming straight in. It seemed that the ball would strike the ground before the redskin could get his hands on it, but John sprinted hard and made a forward dive as he ran.

The ball struck in the hands of the fielder when it was not over six inches from the ground. Swiftwing held it.

Teller and Skew were racing round the bases, having been coached to go along. Teller had reached third and was going home, while Skew had passed over to second.

Instead of trying to head off Skew by throwing to third, Swiftwing threw to second. Rattleton took the throw, while Skew reached third. Then Rattleton threw to first.

Frank called the umpire and asked him to announce the batter and two runners ahead of him out.

“What’s the matter with you?” demanded the umpire, as if greatly amazed. “There is nobody out.”

“What?” exclaimed Merry, astounded. “Why, the three men are out, and you know it!”

“Tell me how?”

“O’Grady is out on Swiftwing’s catch of his long drive, and the other men are out for having been caught off their bases on a ball that was caught before it touched the ground.”

“Look here!” cried the umpire, “whom do you take me for? I know something about this game, and I have a good pair of eyes. Your Indian didn’t catch that ball.”

“He didn’t?”

“No!”

“Why not?”

“Because he picked it up just after it struck the ground. I saw him do it.”

The words of the umpire caused great excitement on Merriwell’s team; but the players kept away and let Frank settle the matter, having been taught to do so.

The crowd had quieted down enough to hear something of what was being said, and great surprise was manifested by the decision.

“It’s an outrage!” exclaimed more than one.

The spectators were angry. A short time before they had been roaring and “rooting” for the home team, but the rank work of the umpire had turned all their sympathy to Merriwell’s team.

“That man is out on first!” shouted an excited spectator, as he stood up and made furious gestures.

“He’s out! he’s out!”

“Both of those runners are out!” yelled another man. “They ran on a fly ball that was caught. Come in, Merriwell!”

Then the crowd began to yell:

“Out! out! out!”

“Play ball!” snarled the umpire. “I have given my decision!”

“But you’ll have to change it,” asserted Frank.

“Never!”

“You know you are wrong, and everybody in that crowd knows it. You have turned the crowd against you by your work.”

“You shut up and play ball!” came savagely from the umpire. “If you don’t, I’ll declare the game forfeited.”

“Go ahead and declare it,” said Merry. “You cannot drive us that way.”

“Will you play ball, or not?”

“Put that umpire out!” roared the crowd. “He’s robbing you, Merriwell!”

“Hear that,” said Frank. “You can see what is thought of your work.”

“I don’t care!”

“Then your decision stands?”

“It does.”

“Come in, boys!” cried Merry. “We go to bat or leave the field.”

He made a gesture, and every man came trotting in from the field.

“Hooray!” cried the crowd. “That’s the talk! That’s right! that’s right!”

Then they cheered loudly.

The captain of the Stars ran out to the umpire, but Frank gave that individual no further attention. When the shouting lulled, the umpire loudly cried:

“I will give Merriwell just one minute to put his men back on the field. If he does not do it in that time I shall declare the game in favor of the Omaha Stars.”

“You’re a thundering big stiff!” bellowed a man on the bleachers.

“He’s a robber—that’s what he is!” cried another man shrilly.

“Robber! robber! robber!” shrilled a lot of small boys.

“I propose we give him what he deserves!” came from the man with the hoarse voice. “Come on!”

Over the rail he leaped, and then there was an upheaval of the angry multitude, men following the leader like a flock of sheep. On to the diamond rushed a mad mob that quickly surrounded the umpire.

Now, that umpire had not expected anything of the sort and he was frightened, for he saw he was[35] in danger of rough treatment. He could not get away, and heavy hands were placed upon him.

“Thump him!”

“Kick him!”

“Tar and feather him!”

“Black his eyes!”

“Soak him!”

The man was in danger of being treated roughly.

Into that angry mob plunged Frank Merriwell, flung men aside, and forced his way to the side of the cheating umpire.

“Stop!” rang out Frank’s clear voice, as he faced the furious mob. “This is what kills baseball!”

“An umpire like that kills it!”

“Kill the umpire!”

“He ought to be lynched!”

“Perhaps he ought to be lynched,” said Merry; “but we didn’t come here to take part in this kind of a game, and I don’t believe Mr. Dorrity, captain of the Stars, wants to steal this game from us. We play honest baseball, or not at all. All we ask of anybody is what we deserve.”

“You’re not getting it from this whelp!”

“I know we are not, but I don’t want this game to end in a riot, and you shall not mob the umpire.”

“Let’s do it, anyhow! He deserves it!” came from one man.

Frank’s team had been forcing its way to Merry’s[36] side, and now, at a sign, they closed round him and infolded the treacherous umpire.

“We are not anxious enough for this game to have it go out that the umpire was mobbed,” said Merry. “We shall protect him.”

“Well, what do you think of that?” exclaimed the hoarse-voiced man.

“This Merriwell takes the cake!” said another man. “Instead of protecting that cheat, I’d hit him over the head with a club, if I were Merriwell!”

“The roaster ought to be soaked with a bat!”

“Are you going to let him rob you of the game, Merriwell?”

“I don’t think Mr. Dorrity will do that,” said Frank.

Dorrity had been trying to reach the umpire, and he finally succeeded.

“You’ll have to change that decision, Derring,” he said. “The crowd won’t stand for it.”

“I gave it just as I saw it,” said Derring. “I can’t change it.”

“Then we’ll have to put in another umpire.”

“You have no right to put me out. An umpire is in for a game.”

“Not if he’s a barefaced robber!” cried somebody. “Put him out!”

“Put him out! put him out!” roared the crowd.

“Where is Chop Morrisy?” cried the captain of the Stars.

“Here,” answered a voice.

“Morrisy, we’ll have to ask you to finish umpiring this game. Won’t you do it for us?”

“I’d rather not.”

“But you will?”

Morrisy hesitated, but finally consented.

“Get out, Derring!” cried the crowd. “Go off and die! Go bag your head!”

Derring was fierce, and he snarled:

“I declare the game forfeited to the Omaha Stars by a score of nine to nothing!”

“And we refuse to accept the forfeit,” said Dorrity promptly. “You are no longer umpire, so you cannot declare it.”

“Off the field with him, boys,” said Frank.

Packed close about Derring, Merry’s men pushed through the mob and hustled the cheating rascal off to the bleachers. As he climbed over the rail the mob howled in derision at him.

Then the field was cleared, and Dorrity announced that the game would go on.

“How are we going to settle Derring’s last decision?” asked Frank. “All three men were out on the play, as you know, Dorrity.”

“I don’t know,” said the captain of the Stars. “In fact, I did not see the catch, as I was urging the man to run. I thought the Indian could not catch the ball.”

“But the crowd saw him do it.”

“Some of my men say it looked like a pick-up.”

“It wasn’t.”

“Well, we’ll put Teller and Skew back on second and first and let O’Grady bat over. That’s fair.”

“Do you think so?”

“Don’t you?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Because they are out.”

“But I’ve given in a point and changed the umpire.”

“I have permitted you to put in anybody you chose as umpire.”

“Oh, come, Merriwell, meet me half-way in this.”

“And give you all the advantage? I am not playing ball that way to-day, Mr. Dorrity. As I have be[39]fore stated, all I want is my due; but that is what I will have if there is any way to get it.”

“Do you mean to refuse to play if those three men are not called out?”

“That’s just what I mean.”

“Why, the umpire will forfeit the game to us.”

“All right.”

“Don’t you ever yield a point?”

“Not in this kind of a game, if I know I am right.”

Dorrity found he could not budge Merriwell, and he reluctantly ordered his men back on the field. The score stood three to two in favor of Frank’s team. But the home team came last to bat.

It was the beginning of the ninth. Browning was the first man up for Merry’s team, and the big fellow advanced heavily to the plate, resolved to start things moving once more. Batch had sized up Browning, and he kept the balls high and close.

Two strikes and two balls were called. Then Bruce popped up an easy one, which was smothered in the first-baseman’s big mitt.

It was a bad start on the ninth. Swiftwing remembered his last turn at bat, and he now did his best to get a hit. He was fortunate enough to meet the ball and drop it over the infield for a safety.

But Rattleton fanned, and two were out. Carker had braced up wonderfully since Merriwell was in the[40] lead, and he went after the ball in very pretty style, picking out the good ones and fouling several.

Two strikes were called on him, and then he met the ball fairly, sending it flying into the outfield. Maloney, the right-fielder, ran for the ball, although it was really in center-field territory.

“Teller! Teller!” cried Dorrity loudly.

But it seemed that Maloney did not hear, for he kept after the ball. The fielders collided and both went down. The ball had struck in the hands of Teller, but Maloney sprang up at once and held it aloft.

“Batter out!” announced the umpire.

“Robber! robber!” cried many. “Teller dropped the ball and Maloney picked it up!”

Frank “kicked” against the decision, but Morrisy stuck to it. Merry had seen the ball strike in Teller’s hands, and he had not seen it pass to the hands of Maloney. The affair was rather singular, yet he could not say he had seen Teller drop the ball. Such being the case, he was compelled to abide by the decision of the umpire. That retired the side, with the score unchanged.

“We must get together and hold the enemy prostrate,” said Ready. “It’s the way to win this game.”

Frank went into the box. Hodge knew Merry would start with the double-shoot, meaning to strike out the first batter up.

Hanson, of the home team, stepped up to the plate. Frank gave him a dazzler, and Hanson fanned.

But again that pain shot the whole length of Frank’s arm, and it felt as if something had broken.

“Guess some of the glass cracked,” thought Frank.

When Bart returned the ball, Merry took plenty of time in delivering it again. Then he tried the double-shoot once more, but threw the sphere high over Bart’s head.

“What’s the matter?” asked Hodge, instantly comprehending that all was not right.

Frank shook his head, but he threw no more double curves. He passed a high one up to Hanson, who hit it into the diamond. Browning tried to field the ball, but it got through him, and Hanson reached the bag.

“Rotten!” cried the crowd.

The coacher warned Hanson to play safe, and Jack, the second-baseman of the Stars, advanced to the plate. Using such skill as he could command with his bad arm, Merry struck Jack out. Hanson had been forced to cling to first.

Maloney followed as a batter. On the first ball pitched Hanson started for second. Maloney slashed at the ball with a wide swing that was intended to baffle Hodge in his throw to second.

Bart put the ball down like a bullet. Hanson was coming fast, and he slid feet first.

It is possible that Rattleton thought of Hanson’s spikes, for he changed his position and muffed the ball. Hanson slid under and was safe.

“Hard luck, Harry!” exclaimed Frank. “You had him if you’d held it!”

“Somebody ought to shoot me!” muttered Rattleton, his face red as a beet.

Frank gave Maloney one close to his hands, and the batter hit it down to Ready. Jack picked the ball up and turned to see where Hanson was. Hanson was about three yards off second, so Ready sent the ball across the diamond to first. The instant Ready threw, Hanson streaked it for third.

Maloney could run like a deer, and he beat the throw to first.

Browning did not wait for a decision, but sent the ball back to Ready, who, seeing Hanson coming, had leaped to cover third. The throw was not accurate, and Jack was pulled off third about two feet, which was enough to save Hanson, who slid round behind him and was safe.

The Stars were fighting for the game. It looked rather dangerous now, but Frank did not let that worry him. Had his wrist been in good condition, he would have found a way to stop the run-getting in short order. But he could not use the double-shoot, and so was compelled to rely on his support when the opposing batters hit him hard. And his support[43] had not been of the first class, except during the first of the game.

Corrigan was a good waiter, but Merry started in to compel him to hit. Maloney went down to second on the first ball pitched.

Hodge threw like a bullet for second. Carson cut in as if intending to take the throw, and this kept Hanson from trying to score.

Seeing Hanson did not try to go home, Carson let the ball pass, and Rattleton caught it, putting it on to Maloney.

“Out at second!” declared the umpire.

This was team-work. Had Hanson started for home, Carson would have caught the ball and driven it straight to the plate to cut him off there. The opposing team had fancied Carson meant to take the ball, anyhow, which is an old trick. In this they had been fooled completely.

Two men were out. Another out without a score would give the game to Merriwell.

Corrigan looked anxious, and Frank tried to work him for a strike-out. Merry got himself into a bad hole, and was compelled to put the ball over. Corrigan hit it fairly and drove it out.

As two men were out already, Hanson did not pause at third, but came home immediately. Swiftwing was forced to make a hard run, and then, as if[44] to offset his former brilliant catch, he muffed the ball.

The score was tied. Corrigan was on first. Dorrity ran in from the coaching-lines and got a bat.

“Score on my hit!” he cried.

Frank gave him a drop, and he let it pass. Then Merry tried a high one, and Dorrity drove it along the ground. The ball went to Carson, struck Berlin’s feet, and flew away off to one side. Ready raced for it, got it, and, in spite of Frank’s warning cry, overthrew to first.

Corrigan came on to third while Browning was after the ball. Bruce got it, and fancied he could nail Corrigan before the runner could make third. In his great haste he threw wild, also, which let Corrigan come home with the winning run.

Merriwell was defeated. And the defeat was due mainly to the ragged support given him by his team.

“My poor heart is broken!” sighed Jack Ready, as Merriwell’s team gathered in Frank’s room at one of the leading hotels in the city. “Alas and alack!”

“It was ‘alack’ of something, else we’d won,” said Merry.

“A lack of ball-playing,” growled Hodge. “We played like a lot of wood-choppers.”

“Oh, Bart, how can you say so?” exclaimed Ready. “We didn’t make more than fifteen or twenty errors and bad plays.”

“Wasn’t my throw to third a bird?” grunted Browning, who was stretched on a comfortable couch.

“It was a match to my throw to first,” said Jack. “They made a beautiful pair of birds.”

“And to think we have met defeat at last!” moaned Greg Carker. “But it is ever thus. Now we can see how others feel when we beat them. This strife for the mastery in this world is a monstrous evil. We see it every day, and it makes brutes and monsters of mankind. The time will come when such strife will cease and perfect harmony will exist; but never can this harmony be known until there has been a great social upheaval—never until——”

“Here comes the earthquake!” cried several of the party.

Greg looked pained.

“Some day the earthquake will come,” he said, “and you, like thousands of others, will be entirely unprepared for it.”

“It was a gug-gug-gol-ding shame to lose that game!” stuttered Gamp. “We had it all nun-nun-nailed down once.”

“I was in poor condition to pitch to-day,” said Frank.

“Nay, nay!” disputed Ready. “It was not that, gentle captain. The team was in poor condition to support any kind of a pitcher. It was one of our ragged days.”

“But I could not use the double-shoot as much as I ought.”

“You can’t play the whole game alone,” muttered Hodge.

“Methinks he has more than once,” said Ready.

“I helped lose the game,” sighed Rattleton. “I feel like hagging my bed—I mean bagging my head!”

“These people will crow over us here,” growled Browning.

“I fancy some spondulicks changed hands on the result of that game,” observed Ready. “The wicked gamester is abroad in the land, and he——”

“Tried to buy Merry off,” finished Hodge. “The whelp did buy the umpire.”

“But we cast that umpire forth, and his influence was felt no longer upon us,” put in Ready. “We can’t lay the blame on the umpire.”

“I won’t get over this in a month!” muttered Hodge bitterly. “It was a hard game to lose.”

“Lul-lul-let’s challenge them to another gug-game!” cried Gamp. “We can dud-dud-do ’em next time!”

“Fellows,” said Frank, “we lost the mascot of the nine, and that’s what ailed us to-day. We played a bad game, but it might have been different if Dick had been with us.”

“Dick was a mascot,” agreed Browning. “Why, that little wizard can pitch ball like a veteran.”

“And Old Joe Crowfoot,” said Frank; “he was not with us. If he had been on hand to powwow round the home plate before the game, he might have put something into the team that seemed lacking.”

“I don’t suppose we’ll ever see that old varmint again?” said Jack questioningly.

“I think we shall,” nodded Merry. “He’s recovering from the wound he received, and I do not believe he will leave Dick when he gets well.”

“Are you going to bother with that soiled old scarecrow?” asked Jack.

“For Dick’s sake, I shall.”

“He’s made you no end of trouble,” declared Hodge. “It was he who induced Dick to rebel.”

“But he has learned his lesson. I saw that he was placed where he could have the very best care and nursing, and I left Dick with him.”

“Don’t expect gratitude from an onery redskin,” said Bart.

Then he looked round quickly and gave a breath of relief on discovering that Swiftwing was not in the room.

“I confess,” said Frank, “that Old Joe’s skin seemed chock full of peskiness, but he has taught Dick many things that no white man could. If I can get the false notions out of the boy’s head, he will be a perfect wonder in time.”

It was only after the death of Frank Merriwell’s father in the West that Merry had learned that he had a half-brother. In his will Mr. Merriwell imposed upon Frank the care of Dick, who had been brought up in the wilds of the West, in the care of Juan Delores, a Spanish refugee. The boy’s constant companion and mentor had been an old Indian, known as Joe Crowfoot. It had been with great difficulty that Frank had forced his young brother to accept him as his guardian, and the boy’s rebellion against Frank’s plans to remove him from his wild life had been encouraged by the old Indian, who loved the wild boy as he would have loved a son. Merry’s powerful[49] will, however, had finally won both the boy and the Indian to him.

“What do you intend to do with Dick?” questioned Carson. “Will you send him to Yale?”

“I hope to; but first he will have to put in some years at school.”

“Where will you send him to school?”

“At Fardale.”

“That’s the place!” nodded Hodge. “He’ll get some of the kinks taken out of him there.”

“One thing fills me with extreme sadness,” said Ready. “That is that the first umpire did not receive his medicine from the crowd to-day.”

“That crowd was rooting for us before the game finished,” laughed Frank.

“And they seemed to feel bad because we lost,” said Rattleton. “We made some friends.”

“For the love of goodness, Merry!” exploded Ready; “is there no way we can get square? Can’t we tackle those fellows again and wipe up the earth with them?”

“If Dick were here——”

“We won games before we knew anything about Dick.”

But, strange to say, Frank seemed to feel that the presence of his young brother was needed in order for them to win.

“I’m not going to talk about it any more,” said[50] Carson. “I am going to get out of this hotel and take a walk.”

The others seemed to feel like doing something of the sort, and they left the room in a body, descending to the office of the hotel, where Frank called for their mail. There happened to be letters for several of the party. Merry received one, which he opened and began to read at once.

As Frank was reading his letter he heard two men talking near at hand. One of them was saying:

“It would draw a big crowd, and there would be money in it. Why don’t you get Merriwell’s team for another game, Wilson?”

“What’s the use?” said a voice that Frank recognized as that of the manager of the Stars. “Those fellows put up the best game they are capable of to-day, and we’d simply beat them to death next time. I don’t want to play any poor games, as that will spoil baseball in this town. The Stars are drawing well now.”

“I know a man who says he’ll bet five hundred even that you can’t beat Merriwell again.”

“He’s crazy!”

“No. It’s Livingstone.”

“Why, Hazen will give him two to one.”

“But Hazen has queered himself to-day. The crowd is onto him. It’s current to-night that he tried[51] to bribe Merriwell, and that, failing in this, he bought Derring.”

“How could he buy Derring?”

“He made signs to him.”

“Bah! How did Derring know what his signs meant?”

“I have heard it said that Derring has been bought before.”

“Don’t believe that rot!”

“Well, I know that he made some terrible decisions, and he would have been mobbed if Merriwell hadn’t protected him.”

“He’s stubborn, and he would not give in—that’s all. I don’t think he really meant to rob the other team.”

“The crowd thought so.”

“Oh, well, I doubt if Merriwell would dare play us again, even if we offered him a game.”

“That is where you make a mistake, Mr. Wilson.”

Frank Merriwell was the speaker, and he stepped forward, having crushed in his hand the letter he had been reading.

“Merriwell!” exclaimed Wilson.

“Yes,” nodded Merry. “I happened to hear some of your conversation just now. I trust you will pardon me, but I was curious when you spoke my name. You have said that I would fear to meet your team again. You are wrong. Not only am I not afraid,[52] but I now challenge you to play us another game day after to-morrow, the winners to take the entire gate-money. I shall publish my challenge in the morning papers.”

“Then,” said Wilson warmly, “we’ll play you, and we won’t give you a run. You are due for a shutout, Mr. Merriwell.”

Several of Merry’s friends had heard him make the challenge, and they were eager to know why he had done so. As they left the hotel, Frank said:

“I have received a letter from Dick.”

“Your brother? What does he say?”

“He’s on his way. He will reach Omaha in the morning.”

“Ah, ha!” cried Ready. “Now I understand why you flung the gauntlet in the teeth of Manager Wilson. You believe we can do his team, with the aid of Richard.”

“Exactly. Dick is bringing Old Crowfoot along, and we’ll get into the Stars in great shape.”

“Will you pitch him against these heavy-hitters?”

“I have not decided on that. If my wrist were right, I’d not think of it.”

“Don’t think of it, anyway!” begged Hodge. “Pitch the game yourself, Merry, and we’ll support you next time.”

“That’s what we will, most mighty one!” declared Ready. “We’ll back you up like a stone wall.”

Within a short distance of the hotel they came face to face with Derring, the treacherous umpire. He was accompanied by Hazen, the gambler.

The moment he saw Merriwell, Derring’s face flamed, and he uttered an exclamation of anger. He had been drinking, and he made straight for Frank.

“I want to see you!” he exclaimed. “T believe you gave the crowd the impression that I was trying to do something crooked to-day. I have a score to settle with you.”

Frank looked at the rascal in surprise and contempt.

“You have more nerve than any man I ever saw,” he declared. “Your work on the field to-day spoke for itself. I did not have to give the impression.”

“But you did it, just the same. You got the crowd down on me.”

“How?”

“By kicking against my decision.”

“I kicked because I was not willing to be robbed.”

“Then you say I was robbing you?”

“Yes!”

“You are a——”

“Stop!” rang out Frank’s voice. “Don’t say it! I protected you from the mob to-day after you did me a dirty turn, but I’ll not hold my hand in case you call me a liar!”

“If you lifted a hand on me,” said Derring, his[54] eyes glaring and his hand moving toward his hip, “I’d shoot you like a dog!”

“If you were quick enough you might, but I doubt if you would.”

Bart Hodge was ready to spring at Derring.

“You had better get out of this town!” grated the umpire. “I give you warning that it isn’t safe for you to stay here!”

“I do not mind your warnings. I shall stay here until after the next game with the Stars.”

“The next game?”

“Yes. We play again day after to-morrow.”

“Well, you’ll be pie. Say, Hazen, that will be your chance to make a stake. Bet all your money on the Stars. The next game will be a walkover.”

“All of that,” nodded Hazen.

“You thought so to-day, sir,” said Frank; “but at one time you were so worried that you tried to bribe me to throw the game. When you failed, you did bribe Derring.”

“It’s false!”

“It’s true! But we’ll win the next game, for all of your crooked work and for all of the umpiring.”

“Just so,” chirped Ready. “We’ll win in a walk, and nothing can stop us. The Stars shall fall, and great will be the fall thereof.”

“Come,” said Frank, to the others; “let’s move on. I do not care to be seen talking to these men.”

That cut both Derring and Hazen.

“Go on!” growled the latter. “I’ll bet my last dollar you lose.”

“Then you’ll be a subject for public charity directly after the game,” assured Ready.

Frank was about to move along when Derring insolently blocked his way and shoved against him. Quick as a flash Merry whirled and grasped the man. Then he gave the rascal a shake that yanked him from beneath his hat.

Derring snarled and struck at Merry. Frank’s patience was exhausted, and he could not hold back the return blow. His fist caught the man under the ear, and down to the sidewalk dropped Mr. Derring.

“Police!” cried Hazen; but he reached for his hip pocket.

“Don’t draw!” warned Merry.

Hazen did not heed. Out came his hand, and it held a revolver.

Instantly Merry’s foot flew out, and the toe of his boot struck the hand of the man, sending the revolver flying into the air.

As the weapon came down Merry caught it, snapped it open, casting out the cartridges, and politely returned it to its owner.

“I beg your pardon,” he said. “Here is your gun. But I believe it is a dangerous thing for you to have round. You might shoot somebody with it.”

Hazen was frothing. Derring struggled up and reached for his hip.

“Look out!” cried Hodge.

Frank was on the alert. He leaped on Derring, twisted his hand from his hip, jerked out the revolver himself, and sent the weapon flying across the street.

“Some of you Western people are extremely careless with your shooting-irons,” he observed. “Come on, fellows.”

Then, accompanied by his friends, he walked away.

Dick Merriwell did arrive in Omaha the following morning, and he brought Old Joe Crowfoot with him. The old redskin was looking thin and weak, and the expression of his wrinkled face was as inscrutable as ever.

“How!” he exclaimed, holding out his hand to Merriwell, as Frank met them at the station.

“How are you, Crowfoot?” exclaimed Merry.

“Heap better,” was the answer.

“That is good. Has the wound healed?”

“Some.”

“Are you strong?”

“Not yet; get so heap soon.”

“Well, I’m glad to see you. I took pains to have everything done for your comfort and to aid in bringing you round as soon as possible.”

“Heap much good!” said the old fellow. “Joe him not forget.”

“Joe will never forget,” assured Dick. “He has told me so many times. He thought at first you were the one who shot him, but now he knows better. We have talked it all over while he has been getting[58] stronger, and he has decided that it is best for me to go with you and do just what you say.”

“Heap so,” nodded Old Joe. “Injun Heart your brother, Steady Hand. You take him now and make him your way. Old Joe him done all he can.”

“And Dick owes you much for what you have done. But where are you going, Joe?”

“Back to mountains—Joe go by himself.”

“That’s it!” cried Dick. “He won’t promise to stay with me.”

Frank placed a hand on the arm of the old Indian.

“Crowfoot,” he said earnestly, “I wish you to stay with Dick. I will take you along, and it shall cost you nothing.”

“White man’s way not Injun’s way.”

“That is true, but you may do as you please.”

“No good.”

“Why not? I will let no one bother you. I give you my word, and my word is good. Isn’t it?”

“Crowfoot him believe Steady Hand.”

“That is all I want. You are old, Joe, and I will see that you are cared for. I feel it a duty. You shall have such clothes as you need, a shelter, and plenty of tobacco.”

“Much good!”

“And you shall see Dick every day. You may be able to teach him many things more. It is your duty to him. You are to see that I do not spoil him by[59] making him too much like a white man. I am his brother, but you shall be his father. Will you do it?”

Old Joe hesitated, looked Frank keenly in the face, as if seeking to ascertain his sincerity, then said:

“Joe him do it!”

“Then that is settled!” exclaimed Frank, in satisfaction.

“When Joe he want to go him go.”

“You shall go whenever you like.”

Dick was delighted by this arrangement.

“Thank you, Frank!” he exclaimed. “Thank you! thank you! Now, if I could only have Felicia——”

“Perhaps you may.”

Dick’s eyes sparkled.

“How can that be possible?” he asked. “She is far away.”

“But her father must understand that the time has come when she should attend school somewhere. Her mother is dead, and can teach her no longer. Mr. Delores may instruct her in Spanish, but she should have a different tutor. I hope to induce her father to bring her East and put her into school.”

“Ugh!” grunted Crowfoot. “Him no do it. Him have heap many enemy. Him stay where him be.”

“We shall see,” said Merry. “I am glad you are here, Dick, for we have missed you on the nine.”

“Missed me?” said the boy, his eyes dancing. “Why,[60] you do not really need me on the nine. You simply played me in order that I might get experience and practise.”

“Who told you so?”

“I don’t know. Anyhow, I thought so.”

“Well, we have played a game without you and lost it. The Stars, of this city, trimmed us yesterday.”

“Oh!” cried Dick, in amazement. “How could they do it?”

“They did it very handsomely.”

“I don’t believe it was square! I don’t believe they could beat you!”

“They did, Dick.”

“And you pitched?”

“With that.”

Frank held up his wrist, about which there was a bandage.

“If you had been here, Dick,” he said, “they could not have won the game.”

This was praise, indeed, and the heart of the boy glowed. It was fine to know that Frank had so much confidence in him.

“I am here now,” he said.

“And we play them again to-morrow.”

“Good! good! We’ll win! You really want me to play, Frank?”

“I want you to play, and I want Old Joe on the bench. The combination will give us good luck.”

“Old Joe him go to see Dick play. Him great little boy at um baseball.”

“Then it is all up with the Omaha Stars,” laughed Frank. “We’ll beat them for sure.”

There was a burst of coarse, sarcastic laughter near at hand, and Frank turned quickly, to see Hazen and Derring there. He looked at the men intently, and they returned his stare in a most insolent manner.

“What do you think of that, Hazen?” laughed Jim Derring. “Merriwell thinks he’ll be able to win the game just because he has that kid to put on the team.”

“I think Merriwell is an idiot,” rumbled Hazen.

A flash of fire came into Dick Merriwell’s dark eyes, and he sprang toward the men.

“Who are you?” he cried. “What do you know about baseball?”

“I knew all about the game before you was born, kid,” said the treacherous umpire.

“Well, you don’t know enough to be a gentleman!” flashed Dick, in his fearless manner.

“What’s that? Why, you little runt, I’ll shake you outer them clothes!”

“Try it! I don’t know who you are, but——”

“Don’t talk to him, Dick,” said Frank, stepping up. “He is nobody but a common rascal who tried to sell[62] the game to this other man yesterday. He was umpiring, and his dirty work made the crowd so angry that it came near mobbing him.”

“It was your dirty kicking that gave the crowd the impression that I was roasting,” snarled Derring. “The Stars will bury you to-morrow. You’ll not get a score.”

“Not a score,” growled Hazen.

“I’ll bet a thousand dollars we beat the Stars!” cried Dick, boylike.

“I’ll take the bet!” came from Hazen. “Put up your money.”

“If I had it, I’d put it up. Frank, let me have the money—do! You may take it out of my share if I lose. But I can’t lose! Won’t you let me have the money?”

Merry shook his head.

“I do not believe in betting, Dick,” he said. “It is gambling, and gambling has ruined many good men.”

Hazen and Derring laughed scornfully.

“You’re a squealer, Merriwell!” declared the stout sporting man. “That’s what’s the matter with you! You lack nerve!”

“That’s not true!” flung back Dick. “Anybody knows better than that!”

“It is true. If he had the least nerve, he would back you up. I took your bet.”

“Knowing you were talking to a mere boy who had no right to make such a bet. It is like you. Anybody else would not have taken him in earnest.”

“Squealer!” sneered Derring.

“Let me have the money, Frank—please!” entreated Dick.

A sudden resolve seized on Merry.

“I’ll let you have it on one condition,” he said.

“Name it.”

“You are not to take the winning yourself, but are to donate it to some charitable institution in this city.”

To this Dick immediately agreed, and then Frank said:

“Mr. Hazen, my brother will meet you an hour from now in the office of the hotel where we are stopping, and we’ll place the money in the hands of the proprietor.”

“If you fail to show up,” said Hazen, “I’ll get up on the bleachers to-morrow and tell everybody how you squealed.”

“Don’t worry; we’ll not fail to show up.”

Then Merry led the way to the place where a cab was waiting. The ex-Yale man, the boy, and the old Indian entered the cab and were driven away.

Frank’s challenge and the acceptance of Manager Wilson had appeared in the Omaha papers, and the result was that a great crowd gathered at the baseball-grounds the afternoon of the day on which the Merries were again to meet the home team.

The Stars were first on the field, and they were given a round of applause. Their practise-work was snappy and aroused no small amount of enthusiasm. Then came Merriwell’s team, trotting out onto the field as the Stars came in.

“Hooray!” shouted a man. “There they are! They’re the boys who play clean baseball!”

The applause received by Frank and his men plainly showed they were favorites.

“Look at the kid!” cried somebody. “Why, are they going to use that boy?”

“They must be crazy!”

“He can’t play ball in this company.”

“He isn’t over fourteen.”

“He’s going in short.”

“Where’s the short-stop they had yesterday?”

“There he goes into right field. The right-fielder is on the bench, I reckon.”

“I’m afraid this game won’t be much like the game yesterday. Our boys will have a snap.”

This seemed to be the fear of most of the spectators, and yet Merriwell’s team received applause for its sharp practise-work.

Carker was batting to the infield, while one of the Stars batted to the outfield. Greg put the first ball down to Dick. It was a slow one, and the boy handled it successfully, throwing over to first on a line.

“That’s pretty good,” said a man.

“But it was easy,” asserted another. “Wait till a hot one comes down.”

A hot one did come down when Greg again batted to Dick, and the boy jumped in front of it, stopped it handsomely, handled it, whistled it across, and won a generous hand from the witnesses.

“I believe the kid can play!” cried a man.

“But he’ll never be able to hit Batch,” asserted another.

The time for the game to be called approached, and now the umpire appeared. Frank called his men in, and Dorrity courteously gave him the choice of innings.

“We’ll start with our outs,” said Merry, and they again entered the field.

“Play ball!”

The voice of the umpire rang out. The batter[66] stepped up to the plate. The crowd settled down to watch the fun.

The batting-orders of the teams were as follows:

| Merries. | Omaha Stars. |

| Ready, 3d b. | Teller, cf. |

| Carson, rf. | Skew, ss. |

| Hodge, c. | O’Grady, lf. |

| Gamp, cf. | Hanson, c. |

| F. Merriwell, p., ss. | Jack, 2d b. |

| Browning, 1st b. | Maloney, rf. |

| Swiftwing, lf. | Corrigan, 3d b. |

| Rattleton, 2d b. | Dorrity, 1st b. |

| D. Merriwell, ss., p. | Batch, p. |

“Remember what we did to him last time, Bill, old boy,” cried Dorrity, as Teller stepped up to the plate. “Get against the first one he puts over.”

Teller grinned.

It was Frank’s practise to put the first ball over, and he did so. Teller did not wait. He cracked the ball hard, and drove it like a bullet straight at Dick Merriwell. It seemed too hot for the boy to handle, and many expected to see Dick try to dodge it. Instead of dodging, however, the lad took the ball, though it made him stagger, and held it.

“Batter out!” announced the umpire.

“Well! well! well!” roared that familiar hoarse voice. “Did you see that? How did he do it?”

“Simplest thing in the world, my good people,” said Jack Ready. “Wait till you see him eat grounders.”

“Pretty, Dick—pretty,” smiled Frank.

Dick laughed.

“It burned my hands,” he admitted; “but it felt good.”

From the moment Frank heard Dick say that that hot ball burned his hands and yet felt good, he never had a doubt concerning the ability of the lad to make a ball-player. The ball-player who is valuable likes the feeling of a ball that comes hot into his clutch, and he is not afraid of being hurt. The moment a man becomes afraid of being hurt he begins to go down-hill as a player, and he is liable to become utterly useless.

Skew was confident when he came up to the plate.

“It was an accident,” he said. “Everybody can hit Merriwell. I’ll get a hit.”

Frank tried to work him, but Skew had a good eye for the ball, and Merry was forced to put it over. Then the batter hit the sphere hard, and it went spinning along the ground just inside the third-base line.

Ready jumped, flung himself forward, thrust down his right hand, and got the ball. It was a marvelous stop, but Jack dropped on one knee in his effort, and Skew was running like the wind to first.

Up sprang Ready, and he whistled the ball across the diamond with the speed of a bullet. Browning smothered it, though forced to stretch at full length on the ground.

“Out at first!” declared Morrisy.

Skew started to raise a kick, but the crowd howled at him, and he closed up.

“Talk about luck!” said O’Grady, as he marched up to the plate. “They can’t keep it up.”

“Put them right over, Merriwell,” cried Rattleton. “You have eight men playing with you.”

“Put one over—put it over!” nodded O’Grady. “I’ll drive it out of the lot.”

Frank accepted the invitation. O’Grady hit it fair, and it went bounding along the ground in a nasty manner between Ready and Dick.

Jack jumped for it, but could not get his hand on the ball. He thought it had gone past for a hit when he turned and saw Dick straightening up with the ball in his hand.

The boy had made another marvelous stop, and he sent the sphere across the diamond to first in time to get the runner.

Three men were out, and the Merries came trotting in from the field.

“Great support, fellows!” said Frank. “That’s what I want to-day. I don’t believe I can throw much of anything in the way of curves. If you continue to back me up like that, the game is ours.”

Ready had his arm over Dick Merriwell’s shoulders.

“He is the baseball wonder of the age!” Jack as[69]serted, in his laughing way. “Up to date, I have regarded myself as it, but the laurels have been torn from my fair brow by a boy. I am green with jealousy.”

“You’re green, anyhow,” said Browning.

“There’s the man I bet with!” exclaimed Dick.

Hazen and Derring were sitting on the bleachers directly behind the visiting players’ bench.

“I hear he put up a large wad on the game,” said Jack. “I think he will lose his little roll to-day, all right, all right.”

As they approached the bench a singular figure rose from somewhere. It was Old Joe Crowfoot, wrapped in his dirty red blanket and smoking his black pipe.

“Ugh!” he exclaimed, his eyes fastened on Dick. “Injun Heart him catch bullet next! Heap good playing!”

Then he sat on the bench beside Dick, of whom he was very proud, though he concealed his pride pretty well.

Ready selected a bat and advanced to the plate.

“Kindly accommodate me by giving me a straight one, Mr. Batch,” he urged. “You know I like you, and I won’t do a thing to you—if I get a chance.”

“Here it is,” said Batch.

But it was a rise, and Jack struck under it a foot.

“I think you are a prevaricator!” said the batter[70] quickly. “I regret very much to apply such a title to you, but it fits like your skin.”

“Well, try the next one,” said Batch.

Jack declined, however, for it was a wide out curve, and a ball was called.

“That makes us even,” said Ready. “Now we’ll begin over.”

The next one was too close, and Jack let it pass.

“Ball two!” cried the umpire.

“Ah-ha!” said Jack. “I’m getting a lead on you.”

Batch set his teeth and put in a drop. Jack struck over it.

“The advantage is mine,” said the pitcher.

“See if you can keep it,” said Ready.

Then Batch tried a high one, and the third ball was called.

“Ha! ha!” said Ready. “Things are coming my way.”

Batch looked resolute, and his next one seemed like a straight ball over the very heart of the plate. Ready went after it, but it proved to be an elusive drop, and was not touched.

“Batter is out!” said the umpire.

Batch laughed at Ready, who retired in a very dejected manner to the bench.

Carson came next, and he waited till Batch put one over. Then Berlin hit the ball hard, but drove it into the air, so that O’Grady easily captured it.

Two men were out, and the crowd began to realize that the game was rather swift.

Hodge looked grim and resolute as he advanced to the plate. He had his favorite stick, and Gamp called:

“Cuc-cuc-cuc-come, now, Hodge, pup-pup-pup-put us into the gug-gug-gug-game! Give us a regular Texas Leaguer!”

Bart was a splendid hitter when in good form, and the outfielders moved back a little, while the infield played deep. Noticing this, Bart suddenly sprang a surprise by bunting the first ball pitched.

The ball rolled down toward third, and Bart was off like a dart for first. The third-baseman was too far away to get it, and the pitcher was too astonished. By the time the catcher got the ball Bart was too near first for a throw to do any good.

“Well! well! well!” cried Ready, as he trotted down to coach. “Why didn’t I think of that? It’s just as easy!”

Batch growled like a dog with a sore ear.

“Couldn’t get a hit any other way,” he said.

Now, Gamp was another heavy hitter, and surely there was no danger that he would bunt. At least, everybody thought so.

Joe, however, was up to snuff, and he saw the Stars were expecting him to swing hard. Thus it happened that, as the ball was pitched, Gamp suddenly[72] shortened his hold on the bat, bunted handsomely, and went prancing down to first, while Hodge raced to second.

Hanson was swearing as he dove after the ball. This time Batch went for it, too, and they collided, the ball rolling off to one side as one of them kicked it.

Bart fancied he saw his opportunity, and he sped for third. Hanson recovered, made a froglike leap for the ball, got it, and threw to third.

Hodge slid, but he was not near enough to reach the bag, and Corrigan tagged him out.

Three men were retired, and neither side had scored in the first inning.

“But we gave ’em an awful fright,” laughed Ready, his apple cheeks glowing.

“I was a fool to try to make third on that!” growled Hodge. “Somebody ought to shoot me!”

“It is taking chances that win games,” said Merry. “If you had reached that bag, we’d all have thought it clever work.”

Frank went into the box again. His arm was feeling bad, but he wished to pitch as much of the game as possible, and he had no thought of giving up for some time.

“Everybody hit him before,” said Dorrity. “Let’s make ’em good this time.”

Hanson was the first man up, and he was breathing heavily. Frank gave him no time to rest, but sent one straight over. Hanson hit it and sent it sailing out for a short hit over the infield. Every one thought it was a hit.

Dick Merriwell raced back after the ball, looking over his shoulder to see it coming down. As it dropped, he jumped forward, caught it with his right hand, dropped it, but caught it with his left before it could fall to the ground.

As the boy turned, with the ball in his hands, the crowd rose up and gave him a cheer.

“Did you ever see anything like that?” roared the man with the hoarse voice.

“Never in my life!” shrieked one with a shrill voice.

“Kid, you’re all right!” came from various quarters.

“Who is that boy?” was the question that passed from lip to lip.