The Project Gutenberg EBook of Island Trail at Walnut Canyon, by Anonymous

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Island Trail at Walnut Canyon

Walnut Canyon National Monument

Author: Anonymous

Release Date: June 30, 2019 [EBook #59840]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ISLAND TRAIL AT WALNUT CANYON ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Lisa Corcoran and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

PRICE 10 CENTS IF YOU TAKE THIS BOOKLET HOME

or you may use it free of charge, returning it to the register stand when you leave....

WALNUT CANYON NATIONAL MONUMENT

11 MILES EAST OF FLAGSTAFF, ARIZONA.

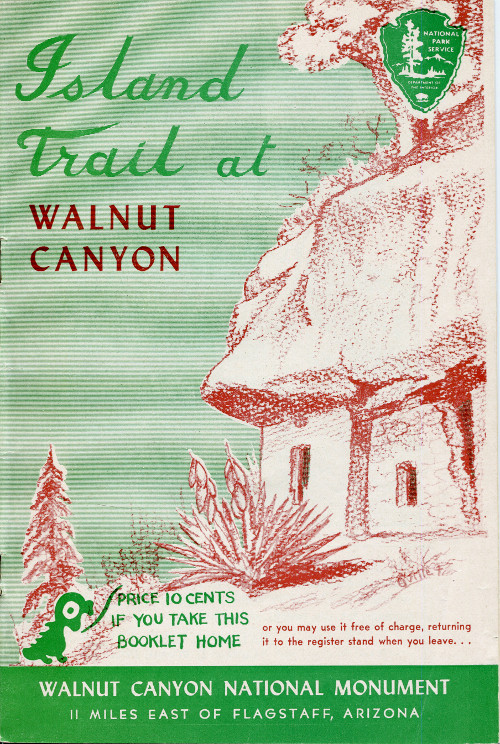

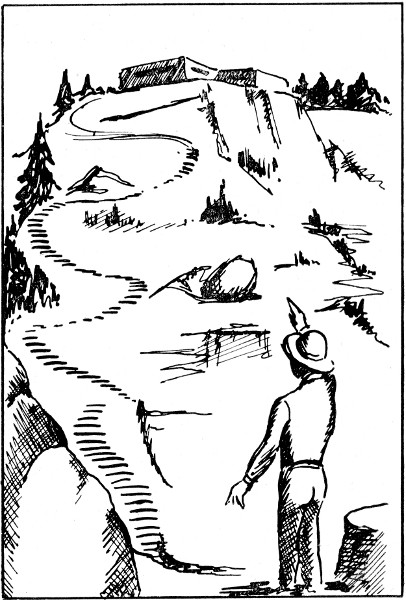

Birdseye view of the “Island” Trail at Walnut Canyon National Monument

The National Park System, of which Walnut Canyon National Monument is a unit, is dedicated to the conservation of America’s scenic, scientific, and historic heritage for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director

The National Park Service sincerely welcomes you to Walnut Canyon National Monument.

* * * * * * * *

In order to insure your safety and to preserve the unspoiled beauty of your National Monument, as well as protect its valuable archeological and historic structures, we urgently request your cooperation in observing the following rules and regulations!

* * * * * * * *

Please do not roll or throw rocks, pick flowers, molest any wildlife, or collect specimens of any kind.

* * * * * * * *

U. S. Department of the Interior

National Park Service

Southwestern National Monuments

* * * * * * * *

At the observation point a self-guiding trail begins which will take you down and around the “Island” in the Canyon. There is a drop of 185 feet by ramp and stairway to the “Saddle.” From there the trail is comparatively flat, and completely encircles the “Island” at the level of the ruins. You will visit several, and be able to see more than 100 of the 400 small cliff dwellings of Walnut Canyon.

Numbered markers along the trail refer to paragraphs in this booklet which explain features of interest at each marker. When you come to numbered markers please read the paragraph with the corresponding number.

Please watch your step at all times. The total length of the trail is five-eighths of a mile and the average time consumed is 40 minutes.

General view of canyon. From this point you will observe that the canyon makes a large “horse shoe” bend leaving an “Island” connected to this side by the narrow neck of land we call the “Saddle.” It is in this small section of the canyon that there is the heaviest concentration of prehistoric cliff-dwellings.

From here you are able to discern the distinctly different types of vegetation growing on opposite sides of the canyon. On the north side (or southern exposure) we see many of the desert type plants native to southern Arizona. On the other side we have the types common in the higher and colder elevations.

Walnut Creek, the stream which cut the canyon, was dammed in 1904 to form Lake Mary which supplies the city of Flagstaff; otherwise there would be a running stream in the canyon today. The early Pueblo Indians probably picked the canyon for their homes for this reason.

They farmed the mesa tops. The natural caves formed by erosion furnished ideal roofs, as well as protection from enemies and comparatively easy access to domestic water supply.

You will now take the trail, to your left, which will lead you to the next stake at the “Saddle.” The trail is steep and there are several flights of stone steps. It is quite safe, but we urge you to use care in your descent.

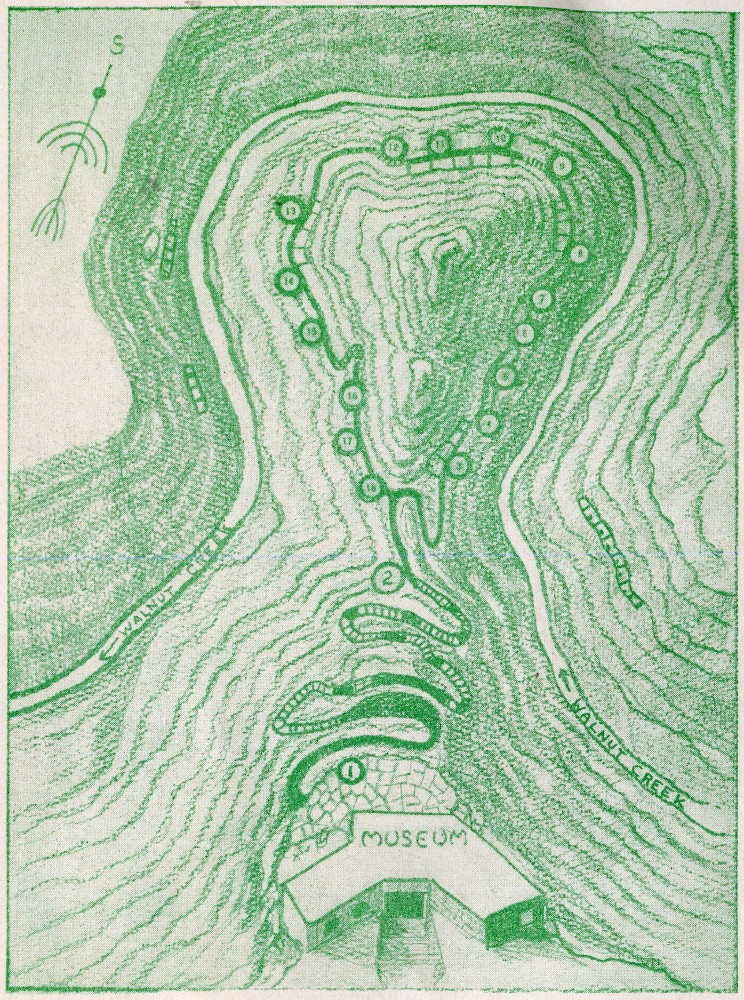

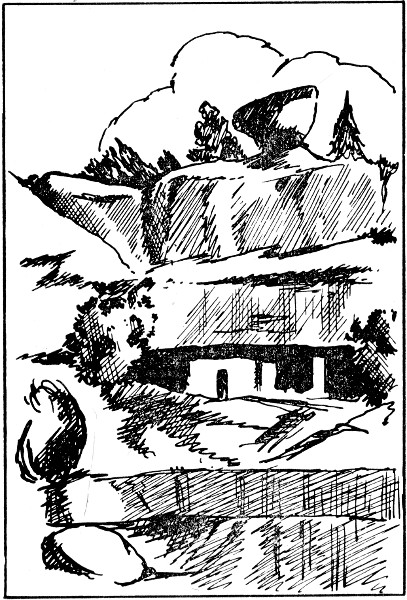

Looking down canyon (to your left) is a graphic view of the geological formations exposed in Walnut Canyon. On the next page of this guide leaflet are sketches showing “How the Canyon was Formed.”

No. 1. Millions of years ago this area was a vast flood plain near sea level. Shifting sands were formed into dunes by wind causing cross bedding or lamination. It is these sands that form the Toroweap Formation which is the oldest exposed in the canyon and is the whorled and cross-bedded sandstone which rises from the Canyon floor.

No. 2. Later this flood plain was submerged, and for millions of years was at the floor of a large, shallow body of water called “The Permian Sea.” Calcium carbonate was precipitated to the floor of the sea. Small sea animals were trapped or covered by this ooze or mire which later compacted into stone and forms the Kaibab Limestone which forms the rim of the canyon, and rests directly on the Toroweap. Many marine fossils are found in this formation.

No. 3. A gradual uplifting of the earth’s surface caused the sea to retreat. Streams draining the land began cutting channels to the sea. The gradual uplift coupled with the cutting action of the stream facilitated canyon cutting. Erosion carried away later Cretaceous deposits from the rim and side erosion began widening the channels. Softer strata would erode more rapidly than the hard, forming the caves in which man later built his homes.

No. 4. Volcanic activity and the forming of the San Francisco Peaks during the next period increased erosion. This activity has continued until fairly recent times. The latest eruption was that of Sunset Crater, occurring around 1066 A.D. Walnut Canyon was dammed to form Lake Mary in 1904. Otherwise there would be running water in the canyon most of the year.

There are practically no records of poisonous snakes at Walnut Canyon. In summer the Coral King Snake with colorful black, white, and orange-red bands may be seen. This snake is harmless and should not be disturbed.

Although not the best preserved of the ruins you will visit, this once was an extensive string of rooms. By tree ring dating we have been able to establish dates of occupancy—the earliest for these masonry dwellings being 1120 A.D. They were abandoned between 1200 and 1300 A.D.

Near the center of the room is what remains of an ancient fireplace—almost obliterated—so please do not walk on it. From here numerous rooms may be seen on this side of the canyon and directly across.

Ponderosa or western yellow pine (also known by 22 other common names) (Pinus ponderosa). The leaves or needles occur in groups of three and are 5 to 11 inches in length. These trees reach an age of from 350 to 500 years and are considered the most important lumber tree in the Rocky Mountain region. Pueblo Indians of today invariably use Ponderosa for their kiva ladders. Hopi Indians attach the needles to prayer plumes to bring cold. The needles are also smoked ceremonially.

How the Canyon Was Formed

Kiva Ladder

Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga taxifolia). This tree requires more moisture than is found on the south slopes of the canyon. The wood is harder, stronger, and more durable than Pine. Douglas Firs are the conspicuous trees on the slopes facing north, while Pinyon and Juniper are dominant on those facing south.

The boughs of this tree are used by many Pueblo Indians today in their ceremonies and dances, particularly by the Hopi who travel long distances to collect the branches for their “Kachina” dances. They believe that the color of the needles in the early spring will foretell growing conditions for the coming year. It probably had similar uses among the cliff dwellers.

Hopi Kachina

This fine overhanging ledge furnished what appears to be an ideal house site, although apparently it was never used as such. Perhaps the women would gather here in the shade on hot days to chat and grind their corn or make pottery. Undoubtedly, Indian children have played in its cool protection.

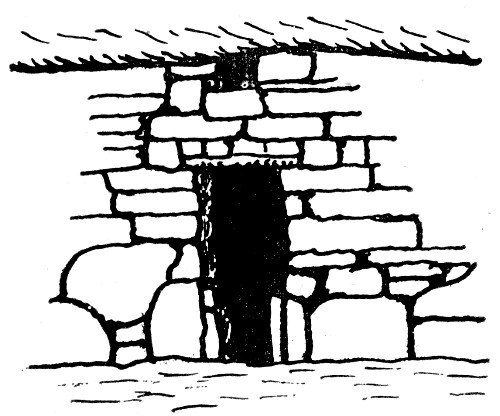

The ledges of this type were used by prehistoric Indians because they afforded good watertight roofs for their homes which could be completed by construction of walls only in front and on the sides. The recesses were formed by a process called differential weathering or exfoliation. Moisture seeps into the cracks behind the surface of the softer layers of limestone. When the water freezes it expands, cracking off thin layers of rock.

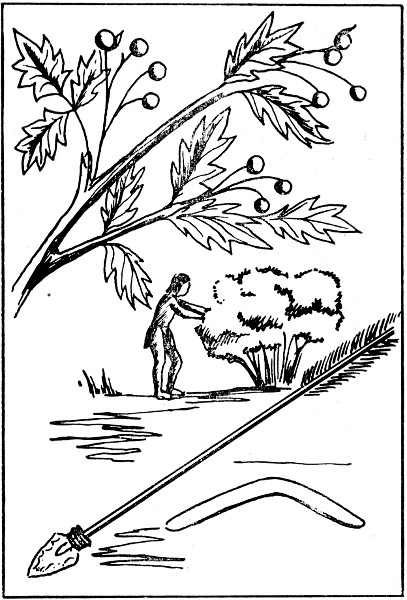

Elderberry (Sambucus corulea neomexicana). 5 The blueblack berries of this plant are eagerly consumed as food by birds and small animals. Berries are put to present-day use in making jams, jellies and pie.

This site once contained five rooms, of which only a few walls are left. You will notice that the vegetation here is different. You are on the northwest side of the “Island,” which receives little sun, is colder, and has vegetation found in the great forests of the northern United States.

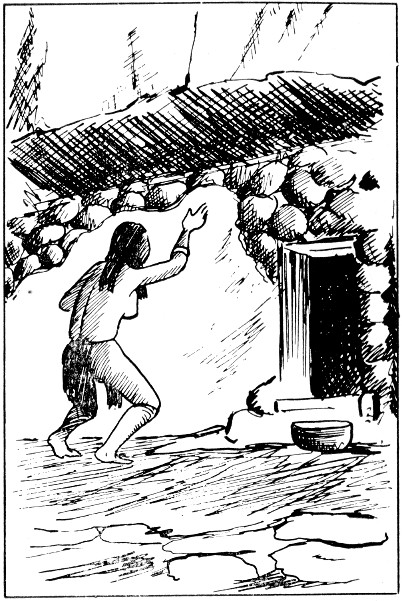

Woman Plastering

These are the best preserved ruins on the trail. Some restoration has been done around the doorways, using a dark mud to distinguish it from the original. The black soot deposit on the ceilings is the result of using pitch Pine for fuel. If you look closely at the inside walls of this room you will see the handprints of the women who plastered it—prints placed here long before America was discovered. Since so many people wish to see them, we ask that you do not touch the wall; otherwise in a few years the handprints would be completely obliterated.

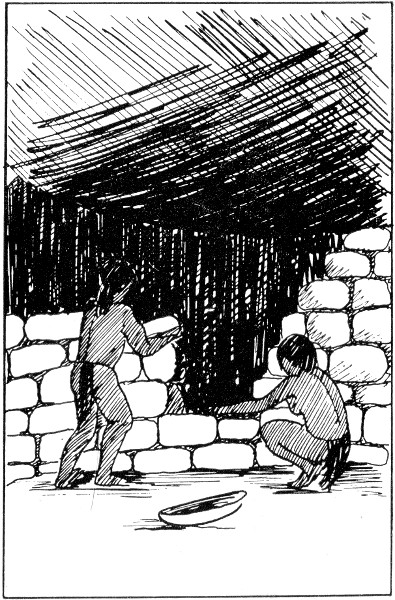

Women Doing Masonry

Note the smoke-blackened rocks inside the wall itself. They show that the stones were re-used from an earlier dwelling, probably constructed at the same site.

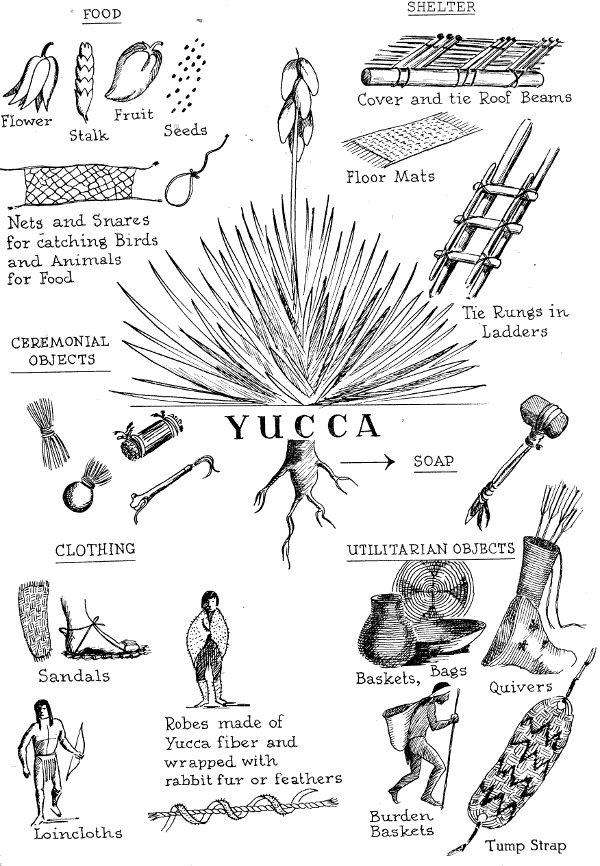

Yucca (Yucca baccata). Also known as “Soapweed” or “Spanish Bayonet.” This plant was most important in the economy of the early cliff dwellers. It furnished all of the necessities of life, namely food, shelter, and clothing. The Yucca is pollinated by a small moth whose larvæ feed on the seeds. The Indians prized the fruit, buds, flowers, and stalks for food. Its fiber was used for baskets, mats, cloth, rope and sandals. Leaves were sometimes laid across rafters or vigas in buildings and covered with mud for roofs. The root makes good soap.

YUCCA

In the construction of houses it is believed that women did much work, certainly the plastering, and possibly the laying of stones in mortar. Men must have helped with the heavier “hod-carrying,” timber-lifting, etc. Women also took care of household duties, made the pottery, and helped with the farming. The men did the hunting, weaving, and farming, and took care of the religious ceremonies and duties. As with their descendants, the historic and present day Pueblo Indians, they were probably matrilineal, that is, the children followed the mother’s clan.

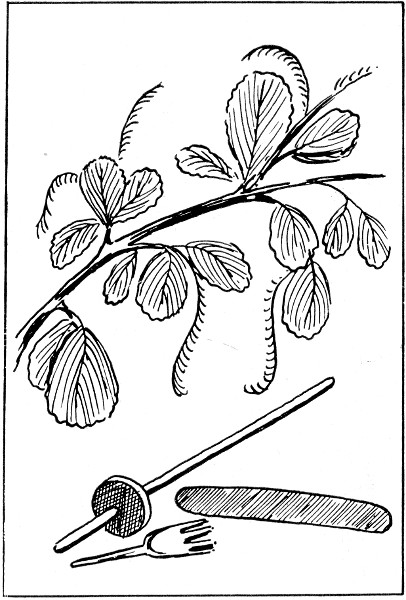

Fremont Barberry

Please note the small opening above the door. The fireplace was built near the center of the room and the smoke escaped through this hole. The T-shaped doorway gave access to the room, and was easily covered during cold weather with a skin, mat, or slab of rock. Each room may have housed a family of four or five. They built terraces, in front of each set of rooms, which served as door steps. The rooms may seem small, but most of the every-day hours were spent outside, and they perhaps used the houses only for cooking and sleeping during inclement weather.

Ruin and Balanced Rock

The hollowed-out stone you see against the wall is a metate (meh-TAH-tay) or corn grinding stone.

Mormon Tea or Torrey Ephedra (Ephedra torreyana). This shrub with its green stems is able to withstand great drought. A pleasant, bitter tea may be brewed with the leaves, which contain tannin. Mormon Tea plant is used medicinally by practically all southwestern Indians.

Little remains of these rooms but piles of rubble. Most of the damage was done by vandals. Portions of only two walls are standing, but directly across the canyon from this point you will see a dwelling in an excellent state of preservation. Originally the walls were covered with plaster 8 so that none of the masonry was visible. Apparently the balanced rock on the rim above this room did not frighten the Indian builders. Rooms built on two separate levels of the cave to the left of this site gave it the appearance of a two-story dwelling.

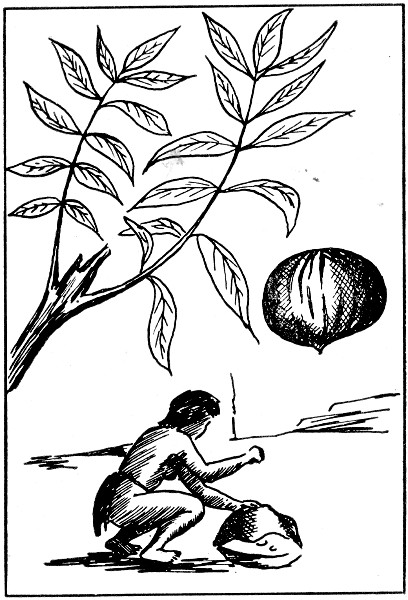

Woman Cracking Walnuts

Juniper (Juniperus scopulorum). Sometimes erroneously called Cedar. Bark was used to pad cradles, make sandals and pot rests. Digging sticks and rakes for farming were also commonly made from this wood. For the Hopi Indians (among whom the nearest direct descendants of these people will be found) this plant has many interesting medicinal and ceremonial uses. The berries are also used as medicine and are eaten sparingly by almost all kinds of wildlife. The wood is good for fuel.

THE TRAIL LEADS UPWARD FROM THIS POINT—PLEASE WATCH YOUR STEP

Fremont Barberry or Hollygrape (Berberis fremonti). This plant is valued by the Hopi for tools of various kinds. Its wood is very strong and makes excellent arrow shafts, Spindles and battens. It is yellow in color and it makes a dye. Medicinally it is utilized for healing gums. It is also good winter browse for deer.

Arizona Walnut (Juglans major). The species after which the Monument was named. The small, thick shelled nuts are eaten by Indians of New Mexico and probably Arizona. A fairly rare tree in the Southwest. This tree is directly below you and identified by the SILVER TAG tied to the branch.

Mountain Mahogany

Mountain Mahogany (Cercocarpus eximus). The wood of this plant was utilized for various implements such as combs and battens for weaving. Its dry wood makes a very hot fire with little smoke. A decoction of the roots of this plant when mixed with Juniper ashes 9 and powdered bark of Alder makes a red dye commonly used for dyeing leather; for example, moccasin uppers.

Looking Up at Museum from Stake No. 18

Don’t Be a Litterbug!

You are now about to begin your ascent back to the museum and your car. We suggest that you rest awhile and enjoy the scenery. Take it easy and stop for an occasional rest. From this point you can see the museum and judge the amount of effort you will have to expend.

We sincerely hope that you have enjoyed your visit and hope that you will COME AGAIN—SOON.

Walnut Canyon National Monument takes its name from the Black Walnut trees found at the bottom of the canyon. It is unusual to find them at an elevation of nearly 6,700 feet.

The National Monument was established by proclamation of President Woodrow Wilson on November 30, 1915, to protect the ancient cliff dwellings of a vanished people. These remains are of great educational, ethnological, and other scientific interest and it is the purpose of the National Park Service to preserve them as near as possible in their original state. Small sections of fallen walls have been repaired and some of the mud plaster or mortar replaced, but no room is more than 10 per cent repaired.

The cliff dwellings were discovered by pioneers and in 1883 James Stevenson visited Walnut Canyon for the Smithsonian Institution. For many years the main road from Flagstaff to Winslow, now Highway 66, ran within a few rods of Walnut Canyon and brought numerous visitors 10 even in horse and buggy days. Promiscuous digging in Indian ruins, “pot hunting,” was then a popular pastime, and the remains of Walnut Canyon suffered from thoughtless individuals who were seeking relics.

In 1921 Dr. Harold S. Colton, director of the Museum of Northern Arizona, made a survey of the cliff dwellings in Walnut Canyon and located 120 sites, which include more than 400 rooms. Perhaps not all the rooms were occupied at the same time but conservative estimates place the maximum population at 500 to 600 Indians.

It is believed that a permanent stream was found in Walnut Canyon when the Indians built their homes. Walnut Canyon is about 400 feet deep and the Indians lived about half way down the side. This required a lot of arduous climbing whenever they went for water, to gather fire wood, to cultivate the fields, or to meet any of their daily needs.

It appears that the Indians’ choice of a homesite in the canyon was guided mainly by where they found natural caves, which might explain why the Indians selected this particular part of the canyon rather than some spot a few miles up or down the stream. Here, too, the main canyon could be entered from a side canyon leading in from the north and emerging practically on the level where most of the cliff dwellings are found. Perhaps the Indians first chose the caves which received the most sunlight in winter, because of the warmth that was gained. As the settlement grew, some families were obliged to live in the less desirable caves which remained shaded throughout the cold days of winter.

Not only was there water and natural shelter in Walnut Canyon, but there was tillable land near the canyon rim where crops would mature without irrigation. The average annual precipitation is about 20 inches and the crops seen from Highways 66 and 89 depend upon rainfall. The cliff dwellers were farmers, as shown by the remains of beans, squash, and the corn cobs found in their homes. Several varieties of both corn and beans were produced.

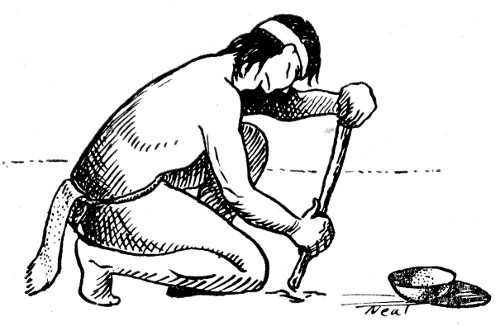

Soil near the canyon’s rim is too shallow and rocky to produce good crops, but by traveling two or three miles to the north, land could be found where the soil is deep enough to retain moisture. Here seeds could be planted with a sharpened stick and tended with a stone hoe. No doubt the cliff dwellers had summer camps near these fields where dark-eyed watchers maintained constant vigil to keep away birds and squirrels seeking to dig up the seeds, and later, the deer, rabbits and other animals that came to eat the tender plants. What a struggle it must have been to raise crops without benefit of steel tools, fences, insecticides, and other advantages now considered necessary.

The Indians farmed at the upper limit of elevations where corn, beans, and squash may be expected to mature, because of the short growing season, which is usually not more than 115 days. Since they had no Weather Bureau, they may have observed the vegetation like certain eastern Indians who watched the oaks until the first leaves were as large as a Red Squirrel’s foot, when they knew it was time to plant their corn. However, there must have been unseasonal frosts such as occurred on August 15, 1949, when present day farmers in this vicinity found their crops severely damaged or completely ruined. Then is when the Indians needed a reserve supply of seed for next year’s planting.

Sunflower seeds were also found in the dwellings, but whether these were cultivated or gathered from wild varieties still abundant in this vicinity is not known.

An understanding of the cliff dweller’s farming activities may be approached by studying the Hopi Indians who live on a reservation about 70 miles north of Winslow, Arizona. Most families have a farm or garden plot where corn, beans, and squash are still the principal crops. At Hotevilla some gardens are found on a terraced hillside, each garden with an embankment around it to retain moisture, and producing a pattern resembling a waffle when seen from above. Some Hopis travel four or five miles on foot each day to cultivate their fields and return home with the setting sun.

Wild fruits which could be gathered by the cliff dwellers include Grapes and Elderberries, both of which are found in the canyon. There is also a Wild Potato sometimes found in the canyon bottom. The tubers are small, seldom as large as small cherries. Perhaps these were eaten with a seasoning of clay, as is the Hopi custom of today. These Indians are known to eat a salty clay with the Wild Potato and the berries of Lycium. This particular clay counteracts the acid which would otherwise make the foods inedible.

Walnut Canyon produces several annual plants which could be boiled and eaten as greens. These include Cleome or Bee Weed, Lambs Quarter, and Mustard.

Among the trash left by these ancient people, archeologists find bones from Deer, Antelope, Turkey, Rabbits, and various waterfowl. Present day visitors are often delighted to see Deer or Antelope along the approach roads to Walnut Canyon and occasionally Turkeys are seen. These are native Wild Turkeys, which in some parts of Arizona are found in sufficient numbers to permit a limited hunting season.

Animals considered good food by living Indians include Coyote, Wolf, Fox, Dog, Wild Cat, Porcupine, Beaver, Badger, Squirrel, Gopher, Kangaroo Rat and Pack Rat. From the available evidence, it appears that the prehistoric cliff dwellers ate the same animals.

Once the Indian family had selected a cave, they did very little to enlarge it. Most of the cliff cavities are rather shallow and extend back 12 into the cliff no more than 10 to 12 feet. The cliff dwellers closed these cavities with masonry walls and partitioned off the rooms. Walls were constructed from rough chunks of limestone gathered wherever found. Apparently there were no quarries. The stones were laid up to form a double wall with the straight faces turned to the outside and the center filled with rubble. Mud was used for both mortar and plaster; in fact most of the mortar and plaster seen in the cliff dwellings today were produced by the Indian builders. Because of humus and foreign matter in the soil there is little suitable material on the canyon ledges. However, a layer of clay is found about 100 feet above the stream bed. This, when pulverized and mixed with water, would produce a satisfactory mortar and plaster.

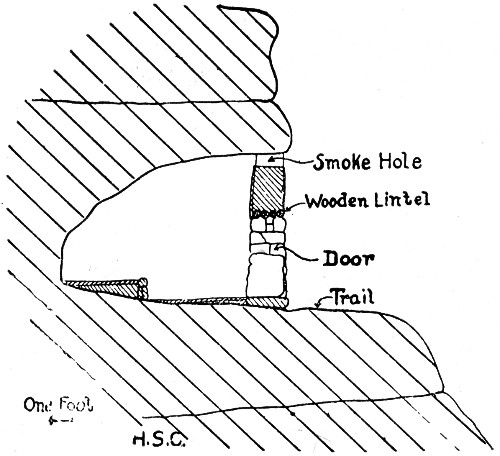

(after Colton)

Door of a Cliff Dwelling Showing Smoke Hole

The rooms vary in size, according to the amount of space available, with an average of about 170 square feet of floor space. The outer wall was set back far enough under the ledge so that rain water running down the cliff would drip outside the wall. The floors were made from hard-packed clay used in sufficient quantity to produce a fairly level surface. Some rooms examined in 1948 were found to have as many as 10 thin layers, none of which exceeded three-eighths of an inch in thickness. Each layer was separated from the other by accumulations of ash and household refuse. The impression is gained that it was easier to lay a new floor than it was to sweep. The back of the cave was sometimes higher than the front, and often was floored separately to form a slightly raised platform or bench.

(after Colton)

Section of Cliff Dwelling

Little wood was used in the construction of a home, since the cave shelter had a solid rock roof. There were pole lintels over the doors, and apparently a few pegs were set into the walls for supporting garments or other paraphernalia.

Construction tools included stone axes, hammers, and picks. In those tools that were hafted, a groove was made three-fourths of the way around the stone to retain a stick bent in the shape of the letter “J” and lashed to form a handle.

Firepits were found in most of the dwellings. These were usually directly in front of the door 4 or 5 feet inside the room. Smoke vents were placed above the door at the top of the wall against the cave roof. Not all the smoke found its way out, as can be seen where the walls and roofs of many rooms are still heavily smoke-blackened. However, there seems to have been a definite attempt to develop circulation of air by adjusting the size of the smoke vent and the door opening.

Fires were kindled with a wooden spindle rotated on a hearth-stick until friction ignited some tinder underneath. The spindle might be made from Holly Grape, the hearth-stick from Yucca, and the tinder from shredded Juniper bark.

Clay pots were used for cooking vessels. These were placed directly over the fire and were able to withstand considerable heat. Some cooking may have been done over a flat rock (or comal) used as a griddle, and other foods could be broiled over the coals.

There was little opportunity for seasoning food. Salt could be obtained from the Verde Valley near Montezuma Castle about 75 miles to the south. No doubt salt was an item of barter which was eagerly sought, and instead of being found in the daily diet it may have been used almost like a confection.

For sweetening they may have used Mescal (or Century Plant). Cactus fruits and dried squash are said to have been used.

A “lemonade” beverage could be made from the berries of Sumac found occasionally on the Monument.

Pueblo Indians are distinguished in the Southwest by a combination of three culture traits. These are the construction of communal houses, the practice of agriculture, and the making of pottery. All these traits were exhibited by the cliff dwellers in Walnut Canyon. Archeologists designate them as the Sinagua (sih-NAH-wah), and place them into the broad classification of the Pueblo III period which marked the zenith of the prehistoric Pueblo culture. There are no kivas in Walnut Canyon. The masonry is usually not coursed, perhaps because of the rough building material available.

Several forces which may have worked singly or in combination to displace the cliff dwellers were drouth, enemy raids, and insanitary conditions. One of the most probable causes of abandonment was drouth. The Sinagua may have found it necessary to augment their water supply by making earthen dams along the lower side of natural pools (particularly farther down the canyon where it broadens). With only a slight decline in annual precipitation the stream would fail entirely in early summer and disrupt the entire community.

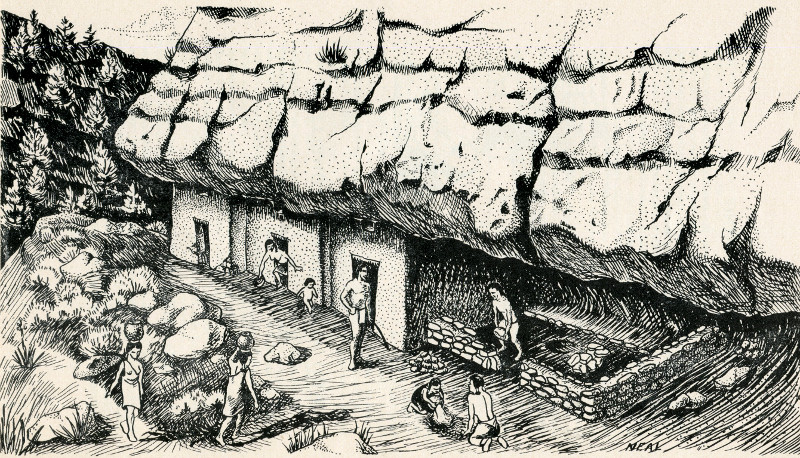

Walnut Canyon Cliff Dwellers at Work

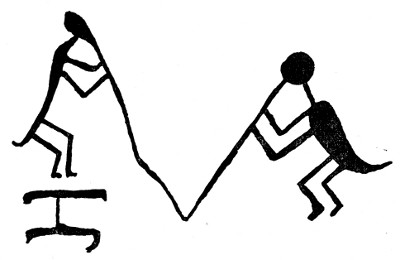

Petroglyph cut on the walls of Walnut Canyon, below the “Island”

A study of the tree rings reveals that a 23-year drouth prevailed in the Southwest from 1276 to 1299 A.D. It appears that the Walnut Canyon cliff dwellers were gone before that time, and perhaps they were displaced by an earlier drouth of less duration.

It is doubtful that the cliff dwellers perished, but rather that their blood flows in the veins of some of the living Pueblo Indians. The Hopis are said to have legends which indicate their ancestors once lived in cliff caves. Hopi Indian visitors sometimes comment on the cliff dwellings being the homes of their ancestors, and there is some evidence to support this. Hopi Indians are of the same basic type which inhabited Walnut Canyon. Studies made on the cliff dwellers’ physical remains reveal they were a short, stocky people much like the Hopi of today.

In addition to pottery making, the Indians did some weaving and basket making. They were acquainted with cotton textiles, and since cotton would not mature at this elevation, they must have traded for raw cotton or the finished products. We do not know the full details of what style clothes these people wore, but we are sure they liked shell beads, pendants, armlets, paint of several colors, and jet buttons.

Turquoise was possessed by some. The nearest known sources are several miles distant, where it was mined from solid rock with stone and wooden tools.

Some shells were imported from points as distant as the Gulf of Lower California over trade routes that have been well defined.

Petroglyphs are rare in the region, perhaps because of the absence of flat sandstone on which to work. The rock pictures have been found at only one spot in the bottom of the canyon and are few.

Some families may have possessed Macaws, since such bones were 16 found in other prehistoric dwellings not far away. Bones of various Owls were found in Nalakihu, a ruin near the Citadel in Wupatki National Monument, but only Hawk bones were found in the Winona ruins near Walnut Canyon.

Walnut Canyon National Monument is at the junction of the Pine with the Pinyon and Juniper belt. Ponderosa Pine trees grow on both sides of the canyon and have golden brown bark. The shorter trees are Pinyon and Juniper, four species of which are known to occur on the Monument. There are scattered clumps of Gambel Oak, and several perennial shrubs of smaller size. One hundred and sixty plant species have been collected, identified, and filed in the herbarium. Several varieties of Penstemon are seen in summer and the Evening Primrose is common.

In addition to the animals mentioned elsewhere, visitors in the warm months may see two kinds of Squirrels and numerous birds including the Raven, Turkey Vulture, Stellar Jay, Nuthatch, and others. In summer, lizards are common and are often found on the outside walls or benches of the museum where they study visitors with considerable interest.

Walnut Canyon is located on a dirt road which forms a loop off Highway 66. From the east the entrance gate is about 4 miles from the paved road, and from the west about 7.

There are no overnight accommodations or camp ground on the Monument, but there is a picnic area. Flagstaff, Arizona, where meals and lodging may be had, is 12 miles from the Monument.

A superintendent and a ranger are in residence on the Monument, and it is open the year around. However, the season of most desirable weather extends from April 1 to November 1.

Many persons visit here each day. If each will preserve the wild flowers, and protect the ruins from defacement, Walnut Canyon will remain a lovely place for future visitors to enjoy. For this reason it is also asked that picnickers leave a dead fire and a clean camp in the designated picnic area.

Because the wild animals—Birds, Squirrels, Foxes, Turkeys, etc.—become tame and trusting in this, their protected refuge, domestic pets should not be allowed to harm them, and must be kept on leash or in cars.

If you smoke, please be very careful while on the trail.

Your suggestions and cooperation will be sincerely appreciated.

This National Monument contains 1,642 acres. Most of it is forested and at times the fire hazard is extreme. Please help us maintain a record of no serious fires, and LET’S KEEP IT CLEAN.

Walnut Canyon National Monument, a unit of the National Park System, is one of the 25 National Monuments administered by the General Superintendent, Southwestern National Monuments, National Park Service, Department of the Interior, Gila Pueblo, Globe, Arizona.

The traveling public is becoming increasingly aware of the National Monuments, which have received less publicity than the great, well-known National Parks, yet which possess extremely interesting features.

Many of these are in the Southwest; we hope you will take the opportunity to visit one or more of them on your trip.

Administered as a group by the General Superintendent,

Southwestern National Monuments, Gila Pueblo, Globe, Arizona

Other areas administered by the National Park Service in the Southwest follow:

This booklet is published by the

SOUTHWESTERN MONUMENTS ASSOCIATION

Box 1562 K—Gila Pueblo, Globe, Arizona

which is a non-profit distributing organization pledged to aid in the preservation and interpretation of Southwestern features of outstanding national interest.

The Association lists for sale hundreds of interesting and excellent publications for adults and children and very many color slides on Southwestern subjects. These make fine gifts for birthdays, parties, and special occasions, and many prove to be of value to children in their school work and hobbies.

May we recommend, for instance, the following items which give additional information on Walnut Canyon National Monument and its environment?

| PAUL THOMAS SERIES | |

|---|---|

| K-10 | A. Wupatki Ruins |

| B. Wupatki Ruins and Amphitheater | |

| C. Sink Hole and Citadel Ruin | |

| D. Lomaki Ruin | |

| E. Box Canyon Ruin and San Francisco Peaks | |

| F. Earth Cracks | |

| SWMA SERIES | |

| B-1a | Wupatki from southwest |

| B-1b | Wupatki from northwest |

| B-1c | Red House in black cinders |

| G46 | Wupatki from southwest (Lollesgard Slide) |

| S-113 | Spectacular Wukoki Ruin near Wupatki |

| S-114 | Citadel Butte and Ruin with Nalakihu Ruin in foreground |

| S-115 | Huge dry sink in the Kaibab Limestone by Citadel Ruin |

| S-116 | Crack-in-Rock Ruin on its sandstone cuesta |

| S-117 | Elaborate prehistoric petroglyphs on red Moenkopi sandstone near Crack-in-Rock Ruin |

| WALNUT CANYON NATIONAL MONUMENT, ARIZONA | |

| SWMA SLIDES | |

| S-107 | Opposite wall of canyon with dwellings taken from “Island” Trail |

| S-108 | Closeup of dwellings seen on “Island” Trail |

| S-109 | Water flowing in canyon west side Island (rare occurrence: when Lake Mary overflows). |

| KELLY CHODA SLIDES | |

| AR58v | Walnut Canyon from Ranger Station |

| AR59 | Ruins under cliffs, Walnut Canyon National Monument |

For the complete list of almost 100 publications and 1700 color slides on Southwestern Indians, geology, ruins, plants, animals, history, etc., ask the Ranger, or you can obtain one by mail by writing the

SOUTHWESTERN MONUMENTS ASSOCIATION

Box 1562 K—Gila Pueblo, Globe, Arizona

End of Project Gutenberg's Island Trail at Walnut Canyon, by Anonymous

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ISLAND TRAIL AT WALNUT CANYON ***

***** This file should be named 59840-h.htm or 59840-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/5/9/8/4/59840/

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Lisa Corcoran and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.