Project Gutenberg's The Decameron (Day 6 to Day 10), by Giovanni Boccaccio

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

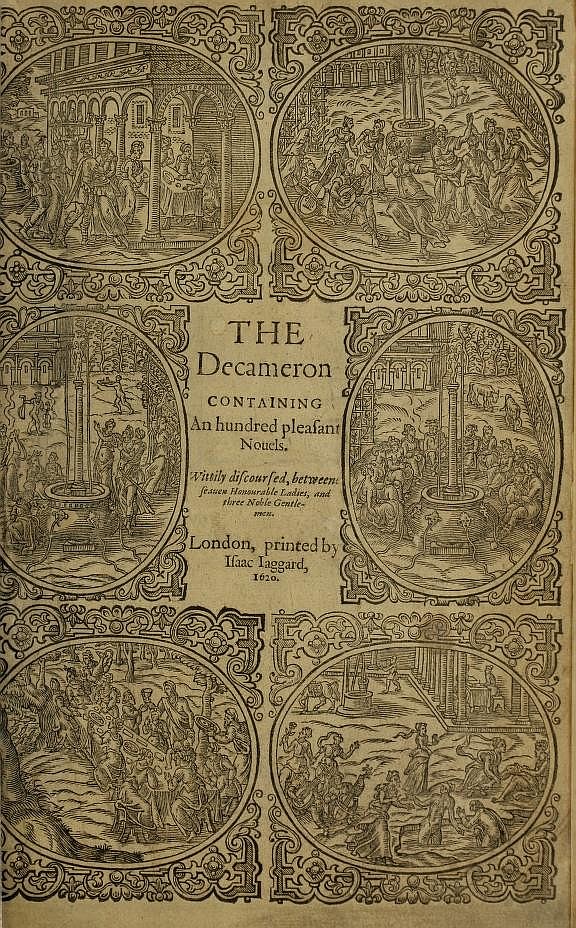

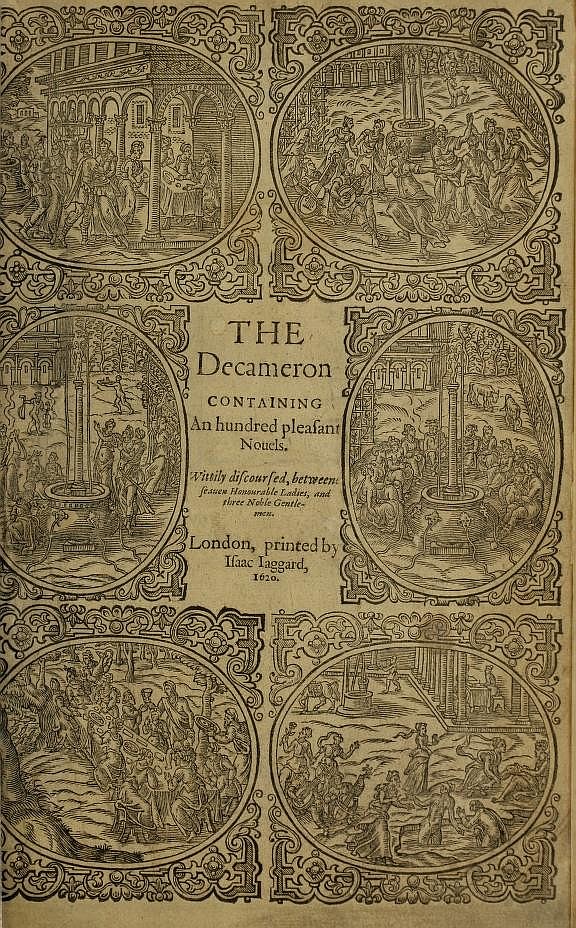

Title: The Decameron (Day 6 to Day 10)

Containing an hundred pleasant Novels

Author: Giovanni Boccaccio

Translator: John Florio

Release Date: July 22, 2016 [EBook #52618]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DECAMERON (DAY 6 TO DAY 10) ***

Produced by Clare Graham and Marc D'Hooghe at

http://www.freeliterature.org (Images generously made

available by the Internet Archive.)

Having (by your Honorable command) translated this Decameron, or Cento Novelle, sirnamed Il Principe Galeotto, of ten dayes severall discourses, grounded on variable and singuler Arguments, happening betweene seaven Noble Ladies, and three very Honourable Gentlemen: Although not attyred in such elegantcy of phrase, or nice curiosity of stile, as a quicker and more sprightly wit could have performed, but in such home-borne language, as my ability could stretch unto; yet it commeth (in all duty) to kisse your Noble hand, and to shelter it selfe under your Gracious protection, though not from the leering eye, and over-lavish tongue of snarling Envy; yet from the power of his blasting poyson, and malice of his machinations.

Bookes (Courteous Reader) may rightly be compared to Gardens; wherein, let the painfull Gardiner expresse never so much care and diligent endeavour; yet among the very fairest, sweetest, and freshest Flowers, as also Plants of most precious Vertue; ill favouring and stinking Weeds, fit for no use but the fire or mucke-hill, will spring and sprout up. So fareth it with Bookes of the very best quality, let the Author bee never so indulgent, and the Printer vigilant: yet both may misse their ayme, by the escape of Errors and Mistakes, either in sense or matter, the one fault ensuing by a ragged Written Copy; and the other thorough want of wary Correction. If then the best Bookes cannot be free from this common infirmity; blame not this then, of farre lighter argument, wherein thy courtesie may helpe us both: His blame, in acknowledging his more sufficiency, then to write so grosse and absurdly: And mine, in pardoning unwilling Errors committed, which thy judgement finding, thy pen can as easily correct.

Farewell.

The Table

The Dedication.

To the Reader.

THE SIXT DAY,

Governed under Madame Eliza.Wherein the Discourses or Novels there to bee recounted, doe concerne such persons; who by some witty words (when any have taunted them) have revenged themselves, in a sudden, unexpected and discreet answere, thereby preventing losse, danger, scorne and disgrace, retorting them on the busi-headed Questioners.

The argument of the first Novell.

A Knight requested Madame Oretta, to ride behinde him on horsebacke, and promised, to tell her an excellent Tale by the way. But the Lady perceiving, that his discourse was idle, and much worse delivered: entreated him to let her walke on foote againe.

The Morall.

Reprehending the folly of such men, as undertake to report discourses, which are beyond their wit and capacity, and gaine nothing but blame for their labour.

The argument of the second Novell.

Cistio a Baker, by a witty answere which he gave unto Messer Geri Spina, caused him to acknowledge a very indiscreet motion, which he had made to the said Cistio.

The Morall.

Approving, that a request ought to be civill, before it should be granted to any one whatsoever.

The Argument of the third Novell.

Madam Nonna de Pulci, by a sodaine answere, did put to silence a Bishop of Florence, and the Lord Marshall: having mooved a question to the said Lady, which seemed to come short of honesty.

The Morall.

Wherein is declared, that mockers doe sometimes meet with their matches in mockery, and to their owne shame.

The Argument of the fourth Novell.

Chichibio, the Cooke to Messer Currado Gianfiliazzi, by a sodaine pleasant answere which he made to his Master; converted his anger into laughter, and thereby escaped the punishment, that Messer meant to impose on him.

The Morall.

Whereby plainely appeareth, that a sodaine witty, and merry answere, doth oftentimes appease the furious choller of an angry man.

The Argument of the fift Novell.

Messer Forese da Rabatte, and Maister Giotto, a Painter by his profession, comming together from Mugello, scornefully reprehended one another for their deformity of body.

The Morall.

Whereby may be observed, that such as will speake contemptibly of others, ought (first of all) to looke respectively on their owne imperfections.

The Argument of the sixt Novell.

A young and ingenious Scholler, being unkindly reviled and smitten by his ignorant Father, and through the procurement of an unlearned Vicare; afterward attained to bee doubly revenged on him.

The Morall.

Serving as an advertisement to unlearned Parents, not to be over-rash, in censuring on Schollers imperfections, through any bad or unbeseeming perswasions.

The Argument of the seaventh Novell.

Madame Phillippa, being accused by her Husband Rinaldo de Pugliese, because he tooke her in Adultery, with a young Gentleman named Lazarino de Guazzagliotori: caused her to bee cited before a Judge. From whom she delivered her selfe, by a sodaine, witty, and pleasant answere, and moderated a severe strict Statute, formerly made against women.

The Morall.

Wherein is declared, of what worth it is to confesse a truth, with a facetious and witty excuse.

The Argument of the eighth Novell.

Fresco da Celatico, counselled and advised his Neece Cesca: That if such as deserved to bee looked on, were offensive to her eyes (as she had often told him;) she should forbeare to looke on any.

The Morall.

In just scorne of such unsightly and ill-pleasing surly Sluts, who imagine none to bee faire or well-favoured, but themselves.

The Argument of the ninth Novell.

Signior Guido Cavalcante, with a sodaine and witty answere, reprehended the rash folly of certaine Florentine Gentlemen, that thought to scorne and flout him.

The Morall.

Notably discovering the great difference that is betweene learning and ignorance, upon Judicious apprehension.

The Argument of the tenth Novell.

Frier Onyon promised certaine honest people of the Country, to shew them a Feather of the same Phoenix, that was with Noah in his Arke. In sted whereof, he found Coales, which he avouched to be those very coales, wherewith the same Phoenix was roasted.

The Morall.

Wherein may be observed, what palpable abuses doe many times passe, under the counterfeit Cloake of Religion.

THE SEAVENTH DAY,

Governed under the Regiment of Dioneus.Wherein the Discourses are directed, for the discovery of such policies and deceits, as women have used for beguiling of their Husbands, either in respect of their love, or for the prevention of some blame or scandall; escaping without sight, knowledge, or otherwise.

The Argument of the first Novell.

John of Lorraine heard one knocke at his doore in the night time, whereupon he awaked his Wife Monna Tessa. Shee made him beleeve, that it was a Spirit which knocked at the doore, and so they arose, going both together to conjure the Spirit with a charme; and afterwards, they heard no more knocking.

The Morall.

Reprehending the simplicity of some sottish Husbands: And discovering the wanton subtilties of some women, to compasse their unlawfull desires.

The Argument of the second Novell.

Peronella hid a young man her Friend and Lover, under a great brewing Fat, uppon the sodaine returning home of her Husband; who tolde her, that he had sold the saide Fat, and brought him that bought it, to carry it away. Peronella replyed, That shee had formerly solde it unto another, who was now underneath it, to see whether it were whole and sound, or no. Whereupon, he being come forth from under it; shee caused her Husband to make it neate and cleane, and so the last buyer carried it away.

The Morall.

Wherein is declared, what hard and narrow shifts and distresses, such as be seriously linked in Love, are many times enforced to undergoe: according as their owne wit, and capacity of their surprizers, drive them to extremities.

The Argument of the third Novell.

Friar Reynard, falling in love with a Gentlewoman, Wife to a man of good account; found the meanes to become her Gossip. Afterward, he being conferring closely with her in her Chamber, and her Husband comming sodainely thither: she made him beleeve, that he came thither for no other ende; but to cure his God-sonne by a charme, of a dangerous disease which he had by wormes.

The Morall.

Serving as a friendly advertisement to married Women, that Monks, Friars, and Priests may be none of their Gossips, in regard of unavoydable perils ensuing thereby.

The Argument of the fourth Novell.

Tofano in the night season, did locke his Wife out of his house, and she not prevailing to get entrance againe, by all the entreaties shee could possibly use: made him beleeve that shee had throwne her selfe into a Well, by casting a great stone into the same Well. Tofano hearing the fall of the stone into the Well, and being perswaded that it was his Wife indeede; came forth of his house, and ranne to the Welles side. In the meane while, his Wife gotte into the house, made fast the doore against her Husband, and gave him many reprochfull speeches.

The Morall.

Wherein is manifested, that the malice and subtilty of a woman, surpasseth all the Art or wit in man.

The Argument of the fift Novell.

A jealous man, clouded with the habite of a Priest, became the Confessour to his owne Wife; who made him beleeve, that she was deepely in love with a Priest, which came every night, and lay with her. By meanes of which confession, while her jealous Husband watched the doore of his house; to surprise the Priest when he came: she that never meant to doe amisse, had the company of a secret friend who came over the toppe of the house to visite her, while her foolish Husband kept the doore.

The Morall.

In just scorne and mockery of such jealous Husbands, that wil be idle headed upon no occasion. And yet when they have good reason for it, doe least of all suspect any such injury.

The Argument of the sixth Novell.

Madame Isabella, delighting in the company of her affected friend, named Lionello, and she being likewise beloved by Signior Lambertuccio: At the same time as shee had entertained Lionello, she was also visited by Lambertuccio. Her Husband returning home in the very instant; she caused Lambertuccio to runne foorth with a drawne sword in his hand, and (by that meanes) made an excuse sufficient for Lionello to her Husband.

The Morall.

Wherein is manifestly discerned, that if Love be driven to a narrow straite in any of his attempts; yet hee can accomplish his purpose by some other supply.

The Argument of the seaventh Novell.

Lodovico discovered to his Mistresse Madame Beatrix, how amourously he was affected to her. She cunningly sent Egano her Husband into his garden, in all respects disguised like herselfe; while (friendly) Lodovico conferred with her the meane while. Afterward, Lodovico pretending a lascivious allurement of his Mistresse, thereby to wrong his honest Master, instead of her, beateth Egano soundly in the Garden.

The Morall.

Whereby is declared, that such as keepe many honest seeming servants, may sometime finde a knave among them, and one that proves to bee over-sawcy with his Master.

The Argument of the Eight Novell.

Arriguccio Berlinghieri, became immeasurably jealous of his Wife Simonida, who fastened a thred about her great toe, for to serve as a signall, when her amourous friend should come to visite her. Arriguccio findeth the fallacy, and while he pursueth the amorous friend, shee causeth her Maide to lie in her bed against his returne: whom he beateth extreamly, cutting away the lockes of her haire (thinking he had done all this violence to his Wife Simonida:) and afterward fetcheth her Mother and Brethren, to shame her before them, and so be rid of her. But they finding all his speeches to be false; and reputing him to be a drunken jealous foole; all the blame and disgrace falleth on himselfe.

The Morall.

Whereby appeareth, that an Husband ought to be very well advised, when he meaneth to discover any wrong offered by his Wife; except he himselfe doe rashly run into all the shame and reproch.

The Argument of the Ninth Novell.

Lydia, a Lady of great beauty, birth, and honour, being Wife to Nicostratus, Governour of Argos, falling in love with a Gentleman, named Pyrrhus; was requested by him (as a true testimony of her unfeigned affection) to performe three severall actions of her selfe. She did accomplish them all, and imbraced and kissed Pyrrhus in the presence of Nicostratus; by perswading him, that whatsoever he saw, was meerely false.

The Morall.

Wherein is declared, that great Lords may sometime be deceived by their wives, as well as men of meaner condition.

The Argument of the tenth Novell.

Two Citizens of Sienna, the one named Tingoccio Mini, and the other Meucio di Tora, affected both one woman, called Monna Mita, to whom the one of them was a Gossip. The Gossip dyed, and appeared afterward to his companion, according as he had formerly promised him to doe, and told him what strange wonders he had seene in the other world.

The Morall.

Wherein such men are covertly reprehended, who make no care or conscience at all of those things that should preserve them from sinne.

THE EIGHTH DAY,

Governed under Madame Lauretta.Whereon all the Discourses, is, Concerning such Witty deceivings, as have, or may be put in practise, by Wives to their Husbands, Husbands to their Wives, Or one man towards another.

The Argument of the First Novell.

Gulfardo made a match or wager, with the wife of Gasparuolo, for the obtaining of her amorous favour, in regard of a summe of money first to be given her. The money he borrowed of her Husband, and gave it in payment to her, as in case of discharging him from her Husbands debt. After his returne home from Geneway, he told him in the presence of his wife, how hee had payde the whole summe to her, with charge of delivering it to her Husband, which she confessed to be true, albeit greatly against her will.

The Morall.

Wherein is declared, That such women as will make sale of their honestie, are sometimes over-reached in their payment, and justly served as they should be.

The Argument of the second Novell.

A lusty Priest of Varlungo, fell in love with a pretty woman, named Monna Belcolore. To compasse his amorous desire, hee left his cloake (as a pledge of further payment) with her. By a subtile sleight afterward, he borrowed a morter of her, which when hee sent home againe in the presence of her husband, he demanded to have his Cloake sent him, as having left it in pawne for the Morter. To pacifie her Husband, offended that she did not lend the Priest the Morter without a pawne: she sent him backe his Cloake againe, albeit greatly against hir will.

The Morall.

Approving, that no promise is to be kept with such women as will make sale of their honesty for Coine.

The Argument of the Third Novell.

Calandrino, Bruno, and Buffalmaco, being Painters by profession, travailed to the Plaine of Mugnone, to finde the precious stone called Helitropium. Calandrino perswading himselfe to have found it, returned home to his house heavy loaden with stones. His wife rebuking him for his absence, he groweth into anger, and shrewdly beates her. Afterward, when the case is debated by his other friends Bruno & Buffalmaco, all is found to be meere folly.

The Morall.

Reprehending the simplicity of such men, as are too much addicted to credulity, and will give credit to every thing they heare.

The Argument of the Fourth Novell.

The Provost belonging to the Cathedrall Church of Fiesola, fell in love with a Gentlewoman, being a widdow, and named Piccarda, who hated him as much as he loved her. He immagining that he lay with her: by the Gentlewomans Brethren, and the Bishop under whom he served, was taken in bed with her Mayde, an ugly, foule, deformed Slut.

The Morall.

Wherein is declared, how love oftentimes is so powerfull in aged men, and driveth them to such doating, that it redoundeth to their great disgrace and punishment.

The Argument of the fift Novell.

Three pleasant companions, plaid a merry prank with a Judge (belonging to the Marquesate of Ancona) at Florence, at such time as he sat on the bench, & hearing criminall causes.

The Morall.

Giving admonition, that for the managing of publike affaires, no other persons are or ought to bee appointed, but such as be honest, and meet to sit on the seate of Authority.

The Argument of the sixt Novell.

Bruno and Buffalmaco stole a young Brawne from Calandrino, and for his recovery thereof, they used a kinde of pretended conjuration, with Pils made of Ginger and strong Malmesey. But insted of this application, they gave him two pils of a Dogges dates or dousets, confected in Alloes, by meanes whereof they made him beleeve, that hee had robd himselfe. And for feare they should report this theft to his Wife, they made him to buy another Brawne.

The Morall.

Wherein is declared, how easily a plaine and simple man may bee made a foole, when he dealeth with crafty companions.

The Argument of the seaventh Novell.

A young Gentleman being a Scholler, fell in love with a Ladie, named Helena, she being a woman, and addicted in affection unto another Gentleman. One whole night in cold winter, she caused the Scholler to expect her comming, in an extreame frost and snow. In revenge whereof, by his imagined Art and skill, he made her to stand naked on the top of a Tower, the space of a whole day, and in the hot moneth of July, to be Sun-burnt and bitten with Waspes and Flies.

The Morall.

Serving as an admonition to all Gentlewomen, not to mocke Gentlemen Schollers, when they make meanes of love to them, except they intend to seeke their owne shame by disgracing them.

The Argument of the eighth Novell.

Two neere dwelling Neighbours, the one beeing named Spinelloccio Tavena, and the other Zeppa di Mino, frequenting each others company daily together; Spinelloccio Cuckolded his Friend and Neighbour. Which happening to the knowledge of Zeppa, hee prevailed so well with the Wife of Spinelloccio, that he being lockt up in a Chest, hee revenged his wrong at that instant, so that neyther of them complained of his misfortune.

The Morall.

Wherein is approved, that hee which offereth shame and disgrace to his neighbour, may receive the like injury (if not worse) by the same man.

The Argument of the Ninth Novell.

Maestro Simone, an idle headed Doctor of Physicke, was thrown by Bruno and Buffalmaco into a common Leystall of filth: the Physitian fondly beleeving, that (in the night time) he should be made one of a new created company, who usually went to see wonders at Corsica, and there in the Leystall they left him.

The Morall.

Approving, that titles of honour, learning, and dignity, are not alwayes bestowne on the wisest men.

The Argument of the tenth Novell.

A Cicilian Curtezan, named Madam Biancafiore, by her subtle policy deceived a young Merchant called Salabetto, of all his mony he had taken for his wares at Palermo. Afterward, he making shew of coming thither againe with far richer Merchandises then before: made the meanes to borrow a great summe of money, leaving her so base a pawne, as well requited her for her former cousenage.

The Morall.

Approving, that such as meet with cunning Harlots, suffering them selves to be deceyved, must sharpen their wits, to make them requitall in the same kind.

THE NINTH DAY,

Governed under Madame Æmillia.Whereon, the Argument of each severall Discourse, is not limited to any one peculiar subject: but everie one remaineth at liberty, to speake of whatsoever themselves best pleaseth.

The Argument of the first Novell.

Madam Francesca, a Widow of Pistoya, being affected by two Florentine Gentlemen, the one named Rinuccio Palermini, and the other Alessandro Chiarmontesi, and she bearing no good will to either of them, ingeniously freed her selfe from both their importunate suites. One of them shee caused to lye as dead in a grave, and the other to fetch him from thence: so neither of them accomplishing what they were enjoyned, failed of their expectation.

The Morall.

Approving, that chast and honest women, ought rather to deny importunate suiters, by subtle and ingenious means, then fall into the danger of scandall and slander.

The Argument of the second Novell.

Madame Usimbalda, Lady Abbesse of a Monastery of Nuns in Lombardie, arising hastily in the night time without a Candle, to take one of her Daughter Nunnes in bed with a young Gentleman, whereof she was enviously accused, by certaine of her other Sisters: The Abbesse her selfe (being at the same time in bed with a Priest) imagining to have put on her head her plaited vayle, put on the Priests breeches. Which when the poore Nunne perceyved; by causing the Abbesse to see her owne error, she got her selfe to be absolved, and had the freer liberty afterward, to be more familiar with her friend, then formerly she had bin.

The Morall.

Whereby is declared, that whosoever is desirous to reprehend sinne in other men, should first examine himselfe, that he be not guiltie of the same crime.

The Argument of the third Novell.

Master Simon the Physitian, by the perswasions of Bruno, Buffalmaco, and a third Companion, named Nello, made Calandrino to beleeve, that he was conceived great with childe. And having Physicke ministred to him for the disease: they got both good fatte Capons and money of him, and so cured him, without any other manner of deliverance.

The Morall.

Discovering the simplicity of some silly witted men, and how easie a matter it is to abuse and beguile them.

The Argument of the Fourth Novell.

Francesco Fortarigo, played away all that he had at Buonconvento, and likewise the money of Francesco Aniolliero, being his Master: Then running after him in his shirt, and avouching that hee had robbed him: he caused him to be taken by Pezants of the Country, clothed himselfe in his Masters wearing garments, and (mounted on his horse) rode thence to Sienna, leaving Aniolliero in his shirt, and walked bare-footed.

The Morall.

Serving as an admonition to all men, for taking Gamesters and Drunkards into their service.

The Argument of the fifte Novell.

Calandrino became extraordinarily enamoured of a young Damosell, named Nicholetta. Bruno prepared a Charme or writing for him, avouching constantly to him, that so soone as he touched the Damosell therewith, she should follow him whithersoever hee would have her. She being gone to an appointed place with him, hee was found there by his wife, and dealt withall according to his deserving.

The Morall.

In just reprehension of those vaine-headed fooles, that are led and governed by idle perswasions.

The Argument of the Sixth Novell.

Two young Gentlemen, the one named Panuccio, and the other Adriano, lodged one night in a poore Inne, whereof one of them went to bed to the Hostes daughter, and the other (by mistaking his way in the darke) to the Hostes wife. He which lay with the daughter, hapned afterward to the Hostes bed, and told him what he had done, as thinking he spake to his owne companion. Discontentment growing betweene them, the mother perceiving her error, went to bed to her daughter, and with discreete language, made a generall pacification.

The Morall.

Wherein is manifested, that an offence committed ignorantly, and by mistaking; ought to be covered with good advise, and civill discretion.

The Argument of the seaventh Novell.

Talano de Molese dreamed, That a Wolfe rent and tore his wives face and throate. Which dreame he told to her, with advise to keep her selfe out of danger; which she refusing to doe, received what followed.

The Morall.

Whereby (with some indifferent reason) it is concluded, that Dreames do not alwayes fall out to be leasings.

The Argument of the Eight Novell.

Blondello (in a merry manner) caused Guiotto to beguile himselfe of a good dinner: for which deceit, Guiotto became cunningly revenged, by procuring Blondello to be unreasonably beaten and misused.

The Morall.

Whereby plainly appeareth, that they which take delight in deceiving others, do well deserve to be deceived themselves.

The Argument of the Ninth Novell.

Two young Gentlemen, the one named Melisso, borne in the City of Laiazzo: and the other Giosefo of Antioch, travailed together unto Salomon, the famous King of Great Britaine. The one desiring to learne what he should do, whereby to compasse and winne the love of men. The other craved to be enstructed, by what meanes hee might reclaime an headstrong and unruly wife. And what answeres the wise King gave unto them both, before they departed away from him.

The Morall.

Containing an excellent admonition, that such as covet to have the love of other men, must first learne themselves, how to love: Also, by what meanes such women as are curst and self willed, may be reduced to civill obedience.

The Argument of the tenth Novell.

John de Barolo, at the instance and request of his Gossip Pietro da Trefanti, made an enchantment, to have his Wife become a Mule. And when it came to the fastening on of the taile, Gossip Pietro by saying she should have no taile at all, spoyled the whole enchantment.

The Morall.

In just reproofe of such foolish men, as will be governed by over-light beleefe.

THE TENTH DAY,

Governed under Pamphilus.Whereon the severall Arguments doe Concerne such persons, as other by way of Liberality, or in Magnificent manner, performed any worthy action, for love, favor, friendship, or any other honourable occasion.

The Argument of the First Novell.

A Florentine knight, named Signior Rogiero de Figiovanni, became a servant to Alphonso, King of Spaine, who (in his owne opinion) seemed but sleightly to respect and reward him. In regard whereof, by a notable experiment, the King gave him a manifest testimony, that it was not through any defect in him, but onely occasioned by the Knights ill fortune; most bountifully recompensing him afterward.

The Morall.

Wherein may evidently be discerned, that Servants to Princes and great Lords, are many times recompenced, rather by their good fortune, then in any regard of their dutifull services.

The Argument of the second Novell.

Ghinotto di Tacco; tooke the Lord Abbot of Clugni as his prisoner, and cured him of a grievous disease, which he had in his stomacke, and afterward set him at liberty. The same Lord Abbot, when hee returned from the Court of Rome, reconciled Ghinotto to Pope Boniface; who made him a Knight, and Lord Prior of a goodly Hospitall.

The Morall.

Wherein is declared that good men doe sometimes fall into bad conditions, onely occasioned thereto by necessity: And what meanes are to be used, for their reducing to goodnesse againe.

The Argument of the third Novell.

Mithridanes envying the life and liberality of Nathan, and travelling thither, with a setled resolution to kill him: chaunceth to conferre with Nathan unknowne. And being instructed by him, in what manner he might best performe the bloody deede, according as hee gave direction, hee meeteth with him in a small Thicket or Woode, where knowing him to be the same man, that taught him how to take away his life: Confounded with shame, hee acknowledgeth his horrible intention, and becommeth his loyall friend.

The Morall.

Shewing in an excellent and lively demonstration, that any especiall honourable vertue, persevering and dwelling in a truly noble soule, cannot be violenced or confounded, by the most politicke attemptes of malice and envy.

The Argument of the fourth Novell.

Signior Gentile de Carisendi, being come from Modena, tooke a Gentlewoman, named Madam Catharina, forth of a grave, wherein she was buried for dead; which act he did, in regard of his former honest affection to the said Gentlewoman. Madame Catharina remaining there afterward, and delivered of a goodly Sonne: was (by Signior Gentile) delivered to her owne Husband; named Signior Nicoluccio Caccianimico, and the young infant with her.

The Morall.

Wherein is shewne, That true love hath alwayes bin, and so still is, the occasion of many great and worthy courtesies.

The Argument of the Fift Novell.

Madame Dianora, the Wife of Signior Gilberto, being immodestly affected by Signior Ansaldo, to free herselfe from his tedious importunity, she appointed him to performe (in her judgement) an act of impossibility; namely, to give her a Garden, as plentifully stored with fragrant Flowers in January, as in the flourishing moneth of May. Ansaldo, by meanes of a bond which he made to a Magitian, performed her request. Signior Gilberto, the Ladyes Husband, gave consent, that his Wife should fulfill her promise made to Ansaldo. Who hearing the bountifull mind of her Husband; released her of her promise: And the Magitian likewise discharged Signior Ansaldo, without taking any thing of him.

The Morall.

Admonishing all Ladies and Gentlewomen, that are desirous to preserve their chastity, free from all blemish and taxation: to make no promise of yeelding to any, under a compact or covenant, how impossible soever it may seeme to be.

The Argument of the Sixt Novell.

Victorious King Charles, sirnamed the Aged, and first of that Name, fell in love with a young Maiden, named Genevera, daughter to an Ancient Knight, called Signior Neri degli Uberti. And waxing ashamed of his Amorous folly, caused both Genevera, and her fayre Sister Isotta, to be joyned in marriage with two Noble Gentlemen; the one named Signior Maffeo da Palizzi, and the other, Signior Gulielmo della Magna.

The Morall.

Sufficiently declaring, that how mighty soever the power of Love is: yet a magnanimous and truly generous heart, it can by no meanes fully conquer.

The Argument of the seaventh Novell.

Lisana, the Daughter of a Florentine Apothecary, named Bernardo Puccino, being at Palermo, and seeing Piero, King of Aragon run at the Tilt; fell so affectionately enamored of him, that she languished in an extreame and long sickenesse. By her owne devise, and means of a Song, sung in the hearing of the King: he vouchsafed to visite her, and giving her a kisse, terming himselfe also to bee her Knight for ever after, hee honourably bestowed her in marriage on a young Gentleman, who was called Perdicano, and gave him liberall endowments with her.

The Morall.

Wherein is covertly given to understand, that howsoever a Prince may make use of his absolute power and authority, towards Maides or Wives that are his Subjects: yet he ought to deny and reject all things, as shall make him forgetfull of himselfe, and his true honour.

The Argument of the Eight Novell.

Sophronia, thinking her selfe to be the maried wife of Gisippus, was (indeed) the wife of Titus Quintus Fulvius, & departed thence with him to Rome. Within a while after, Gisippus also came thither in very poore condition, and thinking that he was despised by Titus, grew weary of his life, and confessed that he had murdred a man, with full intent to die for the fact. But Titus taking knowledge of him, and desiring to save the life of Gisippus, charged himself to have done the bloody deed. Which the murderer himself (standing then among the multitude) seeing, truly confessed the deed. By meanes whereof, all three were delivered by the Emperor Octavius; and Titus gave his Sister in mariage to Gisippus, giving them also the most part of his goods & inheritances.

The Morall.

Declaring, that notwithstanding the frownes of Fortune, diversity of occurrences, and contrary accidents happening: yet love and friendship ought to be preciously preserved among men.

The Argument of the Ninth Novell.

Saladine, the great Soldan of Babylon, in the habite of a Merchant, was honourably received and welcommed, into the house of Signior Thorello d'Istria. Who travelling to the Holy Land, prefixed a certaine time to his Wife, for his returne backe to her againe, wherein, if he failed, it was lawfull for her to take another Husband. By clouding himselfe in the disguise of a Faulkner, the Soldan tooke notice of him, and did him many great honours. Afterward, Thorello falling sicke, by Magicall Art, he was conveighed in one night to Pavia, when his Wife was to be married on the morrow: where making himselfe knowne to her, all was disappointed, and shee went home with him to his owne house.

The Morall.

Declaring what an honourable vertue Courtesie is, in them that truely know how to use them.

The Argument of the tenth Novell.

The Marquesse of Saluzzo, named Gualtiero, being constrained by the importunate solliciting of his Lords, and other inferiour people, to joyne himselfe in marriage; tooke a woman according to his owne liking, called Grizelda, she being the daughter of a poore Countriman, named Janiculo, by whom he had two children, which he pretended to be secretly murdered. Afterward, they being grown to yeres of more stature, and making shew of taking in marriage another wife, more worthy of his high degree and Calling: made a seeming publique liking of his owne daughter, expulsing his wife Grizelda poorely from him. But finding her incomparable patience; more dearely (then before) hee received her into favour againe, brought her home to his owne Pallace, where (with her children) hee caused her and them to be respectively honoured, in despight of all her adverse enemies.

The Morall.

Set downe as an example or warning to all wealthie men, how to have care of marrying themselves. And likewise to poore and meane women, to be patient in their fortunes, and obedient to their husbands.

The Moone having past the heaven, lost her bright splendor, by the arising of a more powerfull light, and every part of our world began to looke cleare: when the Queene (being risen) caused all the Company to be called, walking forth afterward upon the pearled dewe (so farre as was supposed convenient) in faire and familiar conference together, according as severally they were disposed, & repetition of divers the passed Novels, especially those which were most pleasing, and seemed so by their present commendations. But the Sunne beeing somewhat higher mounted, gave such a sensible warmth to the ayre, as caused their returne backe to the Pallace, where the Tables were readily covered against their comming, strewed with sweet hearbes and odoriferous flowers, seating themselves at the Tables (before the heat grew more violent) according as the Queene commanded.

After dinner, they sung divers excellent Canzonnets, and then some went to sleepe, others played at the Chesse, and some at the Tables: But Dioneus and Madam Lauretta, they sung the love-conflict betweene Troylus and Cressida. Now was the houre come, of repairing to their former Consistory or meeting place, the Queene having thereto generally summoned them, and seating themselves (as they were wont to doe) about the faire fountaine. As the Queene was commanding to begin the first Novell, an accident suddenly happened, which never had befalne before: to wit, they heard a great noyse and tumult, among the houshold servants in the Kitchin. Whereupon, the Queene caused the Master of the Houshold to be called, demaunding of him, what noyse it was, and what might be the occasion thereof? He made answere, that Lacisca and Tindaro were at some words of discontentment, but what was the occasion thereof, he knew not. Whereupon, the Queene commanded that they should be sent for, (their anger and violent speeches still continuing) and being come into her presence, she demaunded the reason of their discord; and Tindaro offering to make answere, Lacisca (being somewhat more ancient then he, and of a fiercer fiery spirit, even as if her heart would have leapt out of her mouth) turned her selfe to him, and with a scornefull frowning countenance, said. See how this bold, unmannerly and beastly fellow, dare presume to speake in this place before me: Stand by (saucy impudence) and give your better leave to answere; then turning to the Queene, thus shee proceeded.

Madam, this idle fellow would maintaine to me, that Signior Sicophanto marrying with Madama della Grazza, had the victory of her virginity the very first night: and I avouched the contrary, because shee had been a mother twise before, in very faire adventuring of her fortune. And he dared to affirme beside, that young Maides are so simple, as to loose the flourishing Aprill of their time, in meere feare of their parents, and great prejudice of their amourous friends. Onely being abused by infinite promises, that this yeare and that yeare they shall have husbands, when, both by the lawes of nature and reason, they are not tyed to tarry so long, but rather ought to lay hold upon opportunity, when it is fairely and friendly offered, so that seldome they come maides to marriage. Beside, I have heard, and know some married wives, that have played divers wanton prancks with their husbands, yet carried all so demurely and smoothly; that they have gone free from publique detection. All which this woodcocke will not credit, thinking me to be so young a Novice, as if I had been borne but yesterday.

While Lacisca was delivering these speeches, the Ladies smiled on one another, not knowing what to say in this case: And although the Queene (five and or severall times) commaunded her to silence; yet such was the earnestnes of her spleen, that she gave no attention, but held on still even untill she had uttered all that she pleased. But after she had concluded her complaint, the Queene (with a smiling countenance) turned towards Dioneus saying. This matter seemeth most properly to belong to you; and therefore I dare repose such trust in you, that when our Novels (for this day) shall be ended, you will conclude the case with a definitive sentence. Whereto Dioneus presently thus replyed. Madam, the verdict is already given, without any further expectation: and I affirme, that Lacisca hath spoken very sensibly, because shee is a woman of good apprehension, and Tindaro is but a puny, in practise and experience, to her.

When Lacisca heard this, she fell into a lowd Laughter, and turning her selfe to Tindaro, sayde: The honour of the day is mine, and thine owne quarrell hath overthrowne thee in the fielde. Thou that (as yet) hath scarsely learned to sucke, wouldest thou presume to know so much as I doe? Couldst thou imagine mee, to be such a trewant in losse of my time, that I came hither as an ignorant creature? And had not the Queene (looking verie frowningly on her) strictly enjoyned her to silence; shee would have continued still in this triumphing humour. But fearing further chastisement for disobedience, both shee and Tindaro were commanded thence, where was no other allowance all this day, but onely silence and attention, to such as should be enjoyned speakers.

And then the Queene, somewhat offended at the folly of the former controversie, commanded Madame Philomena, that she should give beginning to the dayes Novels: which (in dutifull manner) shee undertooke to doe, and seating her selfe in formall fashion, with modest and very gracious gesture, thus she began.

Gracious Ladies, like as in our faire, cleere, and serene seasons, the Starres are bright ornaments to the heavens, and the flowry fields (so long as the spring time lasteth) weare their goodliest Liveries, the Trees likewise bragging in their best adornings: Even so at friendly meetings, short, sweet, and sententious words, are the beauty & ornament of any discourse, savouring of wit and sound judgement, worthily deserving to be commended. And so much the rather, because in few and witty words, aptly suting with the time and occasion, more is delivered then was expected, or sooner answered, then rashly apprehended: which, as they become men verie highly, yet do they shew more singular in women.

True it is, what the occasion may be, I know not, either by the badnesse of our wittes, or the especiall enmitie betweene our complexions and the celestiall bodies: there are scarsely any, or very few Women to be found among us, that well knowes how to deliver a word, when it should and ought to be spoken; or, if a question bee mooved, understands to suite it with an apt answere, such as conveniently is required, which is no meane disgrace to us women. But in regard, that Madame Pampinea hath already spoken sufficiently of this matter, I meane not to presse it any further: but at this time it shall satisfie mee, to let you know, how wittily a Ladie made due observation of opportunitie, in answering of a Knight, whose talke seemed tedious and offensive to her.

No doubt there are some among you, who either do know, or (at the least) have heard, that it is no long time since, when there dwelt a Gentlewoman in our Citie, of excellent grace and good discourse, with all other rich endowments of Nature remaining in her, as pitty it were to conceale her name: and therefore let me tell ye, that shee was called Madame Oretta, the Wife to Signior Geri Spina. She being upon some occasion (as now we are) in the Countrey, and passing from place to place (by way of neighbourly invitations) to visite her loving Friends and Acquaintance, accompanied with divers Knights and Gentlewomen, who on the day before had dined and supt at her house, as now (belike) the selfe-same courtesie was intended to her: walking along with her company upon the way; and the place for her welcome beeing further off then she expected: a Knight chanced to overtake this faire troop, who well knowing Madam Oretta, using a kinde and courteous salutation, spake thus unto her.

Madam, this foot travell may bee offensive to you, and were you so well pleased as my selfe, I would ease your journey behinde mee on my Gelding, even so farre as you shall command me: and beside, wil shorten your wearinesse with a Tale worth the hearing. Courteous Sir (replyed the Lady) I embrace your kinde offer with such acceptation, that I pray you to performe it; for therein you shall doe me an especiall favour. The Knight, whose Sword (perhappes) was as unsuteable to his side, as his wit out of fashion for any readie discourse, having the Lady mounted behinde him: rode on with a gentle pace, and (according to his promise) began to tell a Tale, which indeede (of it selfe) deserved attention, because it was a knowne and commendable History, but yet delivered so abruptly, with idle repetitions of some particulars three or foure severall times, mistaking one thing for another, and wandering erroneously from the essentiall subject, seeming neere an end, and then beginning againe: that a poore Tale could not possibly be more mangled, or worse tortured in telling, then this was; for the persons therein concerned, were so abusively nicke-named, their actions and speeches so monstrously misshapen, that nothing could appeare to be more ugly.

Madame Oretta, being a Lady of unequalled ingenuitie, admirable in judgement, and most delicate in her speech, was afflicted in soule, beyond all measure; overcome with many colde sweates, and passionate heart-aking qualmes, to see a Foole thus in a Pinne-fold, and unable to get out, albeit the doore stood wide open to him, whereby shee became so sicke; that, converting her distaste to a kinde of pleasing acceptation, merrily thus she spake. Beleeve me Sir, your horse trots so hard, & travels so uneasily; that I entreate you to let me walke on foot againe.

The Knight, being (perchance) a better understander, then a Discourser; perceived by this witty taunt, that his Bowle had run a contrarie bias, and he as farre out of Tune, as he was from the Towne. So, lingering the time, untill her company was neerer arrived: hee lefte her with them, and rode on as his Wisedome could best direct him.

The words of Madame Oretta, were much commended by the men and women; and the discourse being ended, the Queene gave command to Madam Pampinea, that shee should follow next in order, which made her to begin in this manner.

Worthy Ladies, it exceedeth the power of my capacitie, to censure in the case whereof I am to speake, by saying, who sinned most, either Nature, in seating a Noble soule in a vile body, or Fortune, in bestowing on a body (beautified with a noble soule) a base or wretched condition of life. As we may observe by Cistio, a Citizen of our owne, and many more beside; for, this Cistio beeing endued with a singular good spirit, Fortune hath made him no better then a Baker. And beleeve me Ladies, I could (in this case) lay as much blame on Nature, as on Fortune; if I did not know Nature to be most absolutely wise, & that Fortune hath a thousand eyes, albeit fooles have figured her to bee blinde. But, upon more mature and deliberate consideration, I finde, that they both (being truly wise and judicious) have dealt justly, in imitation of our best advised mortals, who being uncertaine of such inconveniences, as may happen unto them, do bury (for their own benefit) the very best and choisest things of esteeme, in the most vile and abject places of their houses, as being subject to least suspition, and where they may be sure to have them at all times, for supply of any necessitie whatsoever, because so base a conveyance hath better kept them, then the very best chamber in the house could have done. Even so these two great commanders of the world, do many times hide their most precious Jewels of worth, under the clouds of Arts or professions of worst estimation, to the end, that fetching them thence when neede requires, their splendor may appeare to be the more glorious. Nor was any such matter noted in our homely Baker Cistio, by the best observation of Messer Geri Spina, who was spoken of in the late repeated Novell, as being the husband to Madame Oretta; whereby this accident came to my remembrance, and which (in a short Tale) I will relate unto you.

Let me then tell ye, that Pope Boniface (with whom the fore-named Messer Geri Spina was in great regard) having sent divers Gentlemen of his Court to Florence as Ambassadors, about very serious and important businesse: they were lodged in the house of Messer Geri Spina, and he employed (with them) in the saide Popes negotiation. It chanced, that as being the most convenient way for passage, every morning they walked on foot by the Church of Saint Marie d'Ughi, where Cistio the Baker dwelt, and exercised the trade belonging to him. Now although Fortune had humbled him to so meane a condition, yet shee added a blessing of wealth to that contemptible quality, and (as smiling on him continually) no disasters at any time befell him, but still he flourished in riches, lived like a jolly Citizen, with all things fitting for honest entertainment about him, and plenty of the best Wines (both White and Claret) as Florence, or any part thereabout yeelded.

Our frolicke Baker perceiving, that Messer Geri Spina and the other Ambassadors, used every morning to passe by his doore, and afterward to returne backe the same way: seeing the season to be somewhat hot & soultry, he tooke it as an action of kindnesse and courtesie, to make them an offer of tasting his white wine. But having respect to his own meane degree, and the condition of Messer Geri; hee thought it farre unfitting for him, to be so forward in such presumption; but rather entred into consideration of some such meanes, whereby Messer Geri might bee the inviter of himselfe to taste his Wine. And having put on him a trusse or thin doublet, of very white and fine Linnen cloath, as also breeches, and an apron of the same, and a white cap upon his head, so that he seemed rather to be a Miller, then a Baker: at such times as Messer Geri and the Ambassadors should daily passe by, hee set before his doore a new Bucket of faire water, and another small vessell of Bologna earth (as new and sightly as the other) full of his best and choisest white Wine, with two small Glasses, looking like silver, they were so cleare. Downe he sate, with all this provision before him, and emptying his stomacke twice or thrice, of some clotted flegmes which seemed to offend it: even as the Gentlemen were passing by, he dranke one or two rouses of his Wine so heartily, and with such a pleasing appetite, as might have moved a longing (almost) in a dead man.

Messer Geri well noting his behaviour, and observing the verie same course in him two mornings together; on the third day (as he was drinking) he said unto him. Well done Cistio, what, is it good, or no? Cistio starting up, forthwith replyed: Yes Sir, the wine is good indeed, but how can I make you to beleeve me, except you taste of it? Messer Geri, eyther in regard of the times quality, or by reason of his paines taken, perhaps more then ordinary, or else, because hee saw Cistio had drunke so sprightly, was very desirous to taste of the Wine, and turning unto the Ambassadors, in merriment he saide. My Lords, me thinks it were not much amisse, if we tooke a taste of this honest mans Wine, perhaps it is so good, that we shall not neede to repent our labour.

Heereupon, he went with them to Cistio, who had caused an handsome seate to be fetched forth of his house, whereon he requested them to sit downe, and having commanded his men to wash cleane the Glasses, he saide. Fellowes, now get you gone, and leave me to the performance of this service; for I am no worse a skinker, then a Baker, and tarry you never so long, you shall not drinke a drop. Having thus spoken, himselfe washed foure or five small glasses, faire and new, and causing a Viall of his best wine to be brought him: hee diligently filled it out to Messer Geri and the Ambassadours, to whom it seemed the very best Wine, that they had drunke of in a long while before. And having given Cistio most hearty thankes for his kindnesse, and the Wine his due commendation: many dayes afterwardes (so long as they continued there) they found the like courteous entertainment, and with the good liking of honest Cistio.

But when the affayres were fully concluded, for which they were thus sent to Florence, and their parting preparation in due readinesse: Messer Geri made a very sumptuous Feast for them, inviting thereto the most part of the honourablest Citizens, and Cistio to be one amongst them; who (by no meanes) would bee seene in an assembly of such State and pompe, albeit he was thereto (by the saide Messer Geri) most earnestly entreated.

In regard of which deniall, Messer Geri commaunded one of his servants, to take a small Bottle, and request Cistio to fill it with his good Wine; then afterward, to serve it in such sparing manner to the Table, that each Gentleman might be allowed halfe a glasse-full at their down-sitting. The Serving-man, who had heard great report of the Wine, and was halfe offended, because he could never taste thereof: tooke a great Flaggon Bottle, containing foure or five Gallons at the least, and comming there-with unto Cistio, saide unto him. Cistio, because my Master cannot have your companie among his friends, he prayes you to fill this Bottle with your best Wine. Cistio looking uppon the huge Flaggon, replied thus. Honest Fellow, Messer Geri never sent thee with such a Message to me: which although the Servingman very stoutly maintained, yet getting no other answer, he returned backe therewith to his Master.

Messer Geri returned the Servant backe againe unto Cistio, saying: Goe, and assure Cistio, that I sent thee to him, and if hee make thee any more such answeres, then demaund of him, to what place else I should send thee? Being come againe to Cistio, hee avouched that his Maister had sent him, but Cistio affirming, that hee did not: the Servant asked, to what place else hee should send him? Marrie (quoth Cistio) unto the River of Arno, which runneth by Florence, there thou mayest be sure to fill thy Flaggon. When the Servant had reported this answer to Messer Geri, the eyes of his understanding beganne to open, and calling to see what Bottle hee had carried with him: no sooner looked he on the huge Flaggon, but severely reproving the sawcinesse of his Servant, hee sayde. Now trust mee, Cistio told thee nothing but trueth, for neither did I send thee with any such dishonest message, nor had the reason to yeeld or grant it.

Then he sent him with a bottle of more reasonable competencie, which so soone as Cistio saw: Yea mary my friend, quoth he, now I am sure that thy Master sent thee to me, and he shall have his desire with all my hart. So, commaunding the Bottle to be filled, he sent it away by the Servant, and presently following after him, when he came unto Messer Geri, he spake unto him after this manner. Sir, I would not have you to imagine, that the huge flaggon (which first came) did any jotte dismay mee; but rather I conceyved, that the small Viall whereof you tasted every morning, yet filled many mannerly Glasses together, was fallen quite out of your remembrance; in plainer tearmes, it beeing no Wine for Groomes or Peazants, as your selfe affirmed yesterday. And because I meane to bee a Skinker no longer, by keeping Wine to please any other pallate but mine owne: I have sent you halfe my store, and heereafter thinke of mee as you shall please. Messer Geri tooke both his guifte and speeches in most thankefull manner, accepting him alwayes after, as his intimate Friend, because he had so graced him before the Ambassadours.

When Madame Pampinea had ended her Discourse, and (by the whole company) the answere and bounty of Cistio, had past with deserved commendation: it pleased the Queene, that Madame Lauretta should next succeed: whereupon verie chearefully thus she beganne.

Faire assembly, Madame Pampinea (not long time since) gave beginning, and Madam Philomena hath also seconded the same argument, concerning the slender vertue remaining in our sexe, and likewise the beautie of wittie words, delivered on apt occasion, and in convenient meetings. Now, because it is needlesse to proceede any further, then what hath beene already spoken: let mee onely tell you (over and beside) and commit it to memorie, that the nature of meetings and speeches are such, as they ought to nippe or touch the hearer, like unto the Sheepes nibling on the tender grasse, and not as the sullen Dogge byteth. For, if their biting be answereable to the Dogges, they deserve not to be termed witty jests or quips, but foule and offensive language: as plainly appeareth by the words of Madame Oretta, and the merry, yet sensible answer of Cistio.

True it is, that if it be spoken by way of answer, and the answerer biteth doggedly, because himselfe was bitten in the same manner before: he is the lesse to bee blamed, because hee maketh payment but with coine of the same stampe. In which respect, an especiall care is to bee had, how, when, with whom, and where we jest or gibe, whereof very many proove too unmindfull, as appeared (not long since) by a Prelate of ours, who met with a byting, no lesse sharpe and bitter, then had first come from himselfe before, as verie briefely I intend to tell you how.

Messer Antonio d'Orso, being Byshoppe of Florence, a vertuous, wise, and reverend Prelate; it fortuned that a Gentleman of Catalogna, named Messer Diego de la Ratta, and Lord Marshall to King Robert of Naples, came thither to visite him. Hee being a man of very comely personage, and a great observer of the choysest beauties in Court: among all the other Florentine Dames, one proved to bee most pleasing in his eye, who was a verie faire Woman indeede, and Neece to the Brother of the saide Messer Antonio.

The Husband of this Gentlewoman (albeit descended of a worthie Family) was, neverthelesse, immeasurably covetous, and a verie vile harsh natured man. Which the Lord Marshall understanding, made such a madde composition with him, as to give him five hundred Ducates of Gold, on condition, that hee would let him lye one night with his wife, not thinking him so base minded as to give consent. Which in a greedy avaritious humour he did, and the bargaine being absolutely agreed on; the Lord Marshall prepared to fit him with a payment, such as it should be. He caused so many peeces of silver to be cunningly guilded, as then went for currant mony in Florence, and called Popolines, & after he had lyen with the Lady (contrary to her will and knowledge, her husband had so closely carried the businesse) the money was duely paid to the cornuted Coxcombe. Afterwards, this impudent shame chanced to be generally knowne, nothing remaining to the wilful Wittoll, but losse of his expected gaine, and scorne in every place where he went. The Bishop likewise (beeing a discreete and sober man) would seeme to take no knowledge thereof; but bare out all scoffes with a well setled countenance.

Within a short while after, the Bishop and the Lord Marshal (alwaies conversing together) it came to passe, that upon Saint Johns day, they riding thorow the City, side by side, and viewing the brave beauties, which of them might best deserve to win the prize; the Byshop espied a young married Lady (which our late greevous pestilence bereaved us of) she being named Madame Nonna de Pulci, and Cousine to Messer Alexio Rinucci, a Gentleman well knowne unto us all. A very goodly beautifull young woman she was, of delicate language, and singular spirite, dwelling close by S. Peters gate. This Lady did the Bishop shew to the Marshall, and when they were come to her, laying his hand uppon her shoulder, he said. Madam Nonna, What thinke you of this Gallant? Dare you adventure another wager with him?

Such was the apprehension of this witty Lady, that these words seemed to taxe her honour, or else to contaminate the hearers understanding, whereof there were great plenty about her, whose judgement might be as vile, as the speeches were scandalous. Wherefore, never seeking for any further purgation of her cleare conscience, but onely to retort taunt for taunt, presently thus she replied. My Lord, if I should make such a vile adventure, I would looke to bee payde with better money.

These words being heard both by the Bishop and Marshall, they felt themselves touched to the quicke, the one, as the Factor or Broker, for so dishonest a businesse, to the Brother of the Bishop; and the other, as receiving (in his owne person) the shame belonging to his Brother. So, not so much as looking each on other, or speaking one word together all the rest of that day, they rode away with blushing cheekes. Whereby we may collect, that the young Lady, being so injuriously provoked, did no more then well became her, to bite their basenesse neerely, that so abused her openly.

Madam Lauretta sitting silent, and the answer of Lady Nonna having past with generall applause: the Queene commanded Madame Neiphila to follow next in order; who instantly thus began. Although a ready wit (faire Ladies) doth many times affoord worthy and commendable speeches, according to the accidents happening to the speaker: yet notwithstanding, Fortune (being a ready helper divers wayes to the timorous) doth often tippe the tongue with such a present reply, as the partie to speake, had not so much leysure as to thinke on, nor yet to invent; as I purpose to let you perceive, by a pretty short Novell.

Messer Currado Gianfiliazzi (as most of you have both seene and knowen) living alwayes in our Citie, in the estate of a Noble Citizen, beeing a man bountifull, magnificent, and within the degree of Knighthoode: continually kept both Hawkes and Hounds, taking no meane delight in such pleasures as they yeelded, neglecting (for them) farre more serious imployments, wherewith our present subject presumeth not to meddle. Upon a day, having kilde with his Faulcon a Crane, neere to a Village called Peretola, and finding her to be both young and fat, he sent it to his Cooke, a Venetian borne, and named Chichibio, with command to have it prepared for his supper. Chichibio, who resembled no other, then (as he was indeede) a plaine, simple, honest merry fellow, having drest the Crane as it ought to bee, put it on the spit, and laide it to the fire.

When it was well neere fully roasted, and gave forth a very delicate pleasing savour; it fortuned that a young Woman dwelling not far off, named Brunetta, and of whom Chichibio was somewhat enamored, entred into the Kitchin, and feeling the excellent smell of the Crane, to please her beyond all savours, that ever she had felt before: she entreated Chichibio verie earnestly, that hee would bestow a legge thereof on her. Whereto Chichibio (like a pleasant companion, and evermore delighting in singing) sung her this answer.

Many other speeches past betweene them in a short while, but in the end, Chichibio, because hee would not have his Mistresse Brunetta angrie with him; cut away one of the Cranes legges from the spit, and gave it to her to eate. Afterward, when the Fowle was served up to the Table before Messer Currado, who had invited certain strangers his friends to sup with him, wondering not a little, he called for Chichibio his Cook; demanding what was become of the Cranes other legge? Whereto the Venetian (being a lyar by Nature) sodainely answered: Sir, Cranes have no more but one legge each Bird. Messer Currado, growing verie angry, replyed. Wilt thou tell me, that a Crane hath no more but one legge? Did I never see a Crane before this? Chichibio persisting resolutely in his deniall, saide. Beleeve me Sir, I have told you nothing but the truth, and when you please, I wil make good my wordes, by such Fowles as are living.

Messer Currado, in kinde love to the strangers that hee had invited to supper, gave over any further contestation; onely he said. Seeing thou assurest me, to let me see thy affirmation for truth, by other of the same Fowles living (a thing which as yet I never saw, or heard of) I am content to make proofe thereof to morrow morning, till then I shall rest satisfied: but, upon my word, if I finde it otherwise, expect such a sound payment, as thy knavery justly deserveth, to make thee remember it all thy life time. The contention ceassing for the night season, Messer Currado, who though he had slept well, remained still discontented in his minde: arose in the morning by breake of day, and puffing & blowing angerly, called for his horses, commanding Chichibio to mount on one of them; so riding on towards the River, where (earely every morning) he had seene plenty of Cranes, he sayde to his man; We shall see anon Sirra, whether thou or I lyed yesternight.

Chichibio perceiving, that his Masters anger was not (as yet) asswaged, and now it stood him upon, to make good his lye; not knowing how he should do it, rode after his Master, fearfully trembling all the way. Gladly he would have made an escape, but hee could not by any possible meanes, and on every side he looked about him, now before, and after behinde, to espy any Cranes standing on both their legges, which would have bin an ominous sight to him. But being come neere to the River, he chanced to see (before any of the rest) upon the banke thereof, about a dozen Cranes in number, each of them standing but upon one legge, as they use to do when they are sleeping. Whereupon, shewing them quickly to Messer Currado, he said. Now Sir your selfe may see, whether I told you true yesternight, or no: I am sure a Crane hath but one thigh, and one leg, as all here present are apparant witnesses, and I have bin as good as my promise.

Messer Currado looking on the Cranes, and well understanding the knavery of his man, replyed: Stay but a little while sirra, & I will shew thee, that a Crane hath two thighes, and two legges. Then riding somwhat neerer to them, he cryed out aloud, Shough, shough, which caused them to set downe their other legs, and all fled away, after they had made a few paces against the winde for their mounting. So going unto Chichibio, he said: How now you lying Knave, hath a Crane two legs, or no? Chichibio being well-neere at his wits end, not knowing now what answer hee should make; but even as it came sodainly into his minde, said: Sir, I perceive you are in the right, and if you would have done as much yesternight, and had cryed Shough, as here you did: questionlesse, the Crane would then have set down the other legge, as these heere did: but if (as they) she had fled away too, by that meanes you might have lost your Supper.

This sodaine and unexpected witty answere, comming from such a logger-headed Lout, and so seasonably for his owne safety: was so pleasing to Messer Currado, that he fell into a hearty laughter, and forgetting all anger, saide. Chichibio, thou hast quit thy selfe well, and to my contentment: albeit I advise thee, to teach mee no more such trickes heereafter. Thus Chichibio, by his sodaine and merry answer, escaped a sound beating, which (otherwise) his master had inflicted on him.

So soone as Madame Neiphila sate silent (the Ladies having greatly commended the pleasant answer of Chichibio) Pamphilus, by command from the Queene, spake in this manner. Woorthy Ladies, it commeth to passe oftentimes, that like as Fortune is observed divers wayes, to hide under vile and contemptible Arts, the most great and unvalewable treasures of vertue (as, not long since, was well discoursed unto us by Madam Pampinea:) so in like manner hath appeared; that Nature hath infused very singular spirits into most misshapen and deformed bodies of men. As hath beene noted in two of our owne Citizens, of whom I purpose to speake in fewe words. The one of them was named Messer Forese de Rabatte, a man of little and low person, but yet deformed in body, with a flat face, like a Terrier or Beagle, as if no comparison (almost) could bee made more ugly. But notwithstanding all this deformity, he was so singularly experienced in the Lawes, that all men held him beyond any equall, or rather reputed him as a Treasury of civill knowledge.

The other man, being named Giotto, had a spirit of so great excellency, as there was not any particular thing in Nature, the Mother and Worke-mistresse of all, by continuall motion of the heavens; but hee by his pen and pensell could perfectly portrait; shaping them all so truly alike and resemblable, that they were taken for the reall matters indeede; and, whether they were present or no, there was hardly any possibility of their distinguishing. So that many times it happened, that by the variable devises he made, the visible sence of men became deceived, in crediting those things to be naturall, which were but meerly painted. By which meanes, hee reduced that singular Art to light, which long time before had lyen buried, under the grosse error of some; who, in the mysterie of painting, delighted more to content the ignorant, then to please the judicious understanding of the wise, he justly deserving thereby, to be tearmed one of the Florentines most glorious lights. And so much the rather, because he performed all his actions, in the true and lowly spirit of humility: for while he lived, and was a Master in his Art, above all other Painters: yet he refused any such title, which shined the more majestically in him, as appeared by such, who knew much lesse then he, or his Schollers either: yet his knowledge was extreamly coveted among them.

Now, notwithstanding all this admirable excellency in him: he was not (thereby) a jot the handsommer man (either in person or countenance) then was our fore-named Lawyer Messer Forese, and therefore my Novell concerneth them both. Understand then, (faire Assemblie) that the possessions and inheritances of Messer Forese and Giotto, lay in Mugello; wherefore, when Holy-dayes were celebrated by Order of Court, and in the Sommer time, upon the admittance of so apt a vacation; Forese rode thither upon a very unsightly Jade, such as a man can can seldome meet with worse. The like did Giotto the Painter, as ill fitted every way as the other; and having dispatched their busines there, they both returned backe towards Florence, neither of them being able to boast, which was the best mounted.

Riding on a faire and softly pace, because their Horses could goe no faster: and they being well entred into yeeres, it fortuned (as oftentimes the like befalleth in Sommer) that a sodaine showre of raine over-tooke them; for avoyding whereof, they made all possible haste to a poore Countrey-mans Cottage, familiarly knowne to them both. Having continued there an indifferent while, and the raine unlikely to cease: to prevent all further protraction of time, and to arrive at Florence in due season: they borrowed two old cloakes of the poore man, of over-worn and ragged Country gray, as also two hoodes of the like Complexion, (because the poore man had no better) which did more mishape them, then their owne ugly deformity, and made them notoriously flouted and scorned, by all that met or overtooke them.

After they had ridden some distance of ground, much moyled and bemyred with their shuffling Jades, flinging the dirt every way about them, that well they might be termed two filthy companions: the raine gave over, and the evening looking somwhat cleare, they began to confer familiarly together. Messer Forese, riding a lofty French trot, everie step being ready to hoise him out of his saddle, hearing Giottos discreete answers to every ydle question he made (for indeede he was a very elegant speaker) began to peruse and surveigh him, even from the foote to the head, as we use to say. And perceiving him to be so greatly deformed, as no man could be worse, in his opinion: without any consideration of his owne misshaping as bad, or rather more unsightly then hee; in a scoffing laughing humour, hee saide. Giotto, doest thou imagine, that a stranger, who had never seene thee before, and should now happen into our companie, would beleeve thee to bee the best Painter in the world, as indeede thou art? Presently Giotto (without any further meditation) returned him this answere. Signior Forese, I think he might then beleeve it, when (beholding you) hee could imagine that you had learned your A. B. C. Which when Forese heard, he knew his owne error, and saw his payment returned in such Coine, as he sold his Wares for.

The Ladies smiled very heartily, at the ready answer of Giotto; untill the Queene charged Madam Fiammetta, that shee should next succeed in order: whereupon, thus she began. The verie greatest infelicity that can happen to a man, and most insupportable of all other, is Ignorance; a word (I say) which hath bin so generall, as under it is comprehended all imperfections whatsoever. Yet notwithstanding, whosoever can cull (graine by graine) the defects incident to humane race; will and must confesse, that wee are not all borne to knowledge: but onely such, whom the heavens illuminating by their bright radiance (wherein consisteth the sourse and well-spring of all science) by little & little, do bestow the influence of their bounty, on such and so manie as they please, who are to expresse themselves the more thankfull for such a blessing. And although this grace doth lessen the misfortune of many, which were over-mighty to bee in all; yet some there are, who by sawcie presuming on themselves, doe bewray their ignorance by theyr owne speeches; setting such behaviour on each matter, and soothing every thing with such gravity, even as if they would make comparison: or (to speake more properly) durst encounter in the Listes with great Salomon or Socrates. But let us leave them, and come to the matter of our purposed Novell.

In a certaine Village of Piccardie, there lived a Priest or Vicar, who beeing meerely an ignorant blocke, had yet such a peremptorie presuming spirite: as, though it was sufficiently discerned, yet hee beguiled many thereby, untill at last he deceyved himselfe, and with due chastisement to his folly.

A plaine Husbandman dwelling in the same Village, possessed of much Land and Living, but verie grosse and dull in understanding; by the entreaty of divers his Friends and Well-willers, some-thing more intelligable then himselfe: became incited, or rather provoked, to send a Sonne of his to the University of Paris, to study there as was fitting for a Scholler. To the end (quoth they) that having but this Son onely, and Fortunes blessings abounding in store for him: hee might like wise have the riches of the minde, which are those true treasures indeede, that Aristippus giveth us advice to be furnished withall.

His Friends perswasions having prevailed, and hee continued at Paris for the space of three yeares: what with the documents he had attayned to, before his going thither, and by meanes of a happie memory in the time of his being there, wherewith no young man was more singularly endued (in so short a while) he attained and performed the greater part of his Studies.

Now, as oftentimes it commeth to passe, the love of a Father (surmounting all other affections in man) made the olde Farmer desirous to see his Sonne: which caused his sending for him with all convenient speede, and obedience urged his as forward willingnesse thereto. The good olde man, not a little joyfull to see him in so good condition and health, and encreased so much in stature since his parting thence: familiarly told him, that he earnestly desired to know, if his minde and body had attained to a competent and equall growth, which within three or foure dayes he would put in practise.

No other helpe had he silly simple man, but Master Vicar must bee the questioner and poser of his son: wherein the Priest was very unwilling to meddle, for feare of discovering his owne ignorance, which passed under better opinion then he deserved. But the Farmer beeing importunate, and the Vicar many wayes beholding to him, durst not returne deniall, but undertooke it very formally, as if he had bene an able man indeede.

But see how Fooles are borne to be fortunate, and where they least hope, there they find the best successe; the simplicitie of the Father, must be the meanes for abusing his Schollerly Son, and a skreene to stand betweene the Priest and his ignorance. Earnest is the olde man to know, what and how farre his Sonne had profited at Schoole, and by what note he might best take understanding of his answeres: which jumping fit with the Vicars vanity, and a warrantable cloake to cover his knavery; he appoints him but one word onely, namely Nescio, wherewith if he answered to any of his demands, it was an evident token, that hee understood nothing. As thus they were walking and conferring in the Church, the Farmer very carefull to remember the word Nescio: it came to passe upon a sodaine, that the young man entred into them, to the great contentment of his Father, who prayed Master Vicar, to make approbation of his Sonne, whether he were learned, or no, and how hee had benefited at the University?

After the time of the daies salutations had past betweene them, the Vicar being subtle and crafty, as they walked along by one of the tombs in the Church; pointing with his finger to the Tombe, the Priest uttered these words to the Scholler.

Quis hic est sepultus?

The young Scholler (by reason it was erected since his departure, and finding no inscription whereby to informe him) answered, as well hee might, Nescio. Immediately the Father, keeping the word perfectly in his memorie, grewe verie angerly passionate; and, desiring to heare no more demaunds: gave him three or foure boxes on the eares; with many harsh and injurious speeches, tearming him an Asse and Villaine, and that he had not learned any thing. His Sonne was pacient, and returned no answer, but plainly perceived, that this was a tricke intended against him, by the malicious treachery of the Priest, on whom (in time) he might be revenged.

Within a short while after, the Suffragane of those parts (under whom the Priest was but a Deputy, holding the benefice of him, with no great charge to his conscience) being abroad in his visitation, sent word to the Vicar, that he intended to preach there on the next Sunday, and hee to prepare in a readinesse, Bonum & Commodum, because hee would have nothing else to his dinner. Heereat Master Vicar was greatly amazed, because he had never heard such words before, neither could hee finde them in all his Breviarie. Hereupon, he went to the young scholler, whom he had so lately before abused, and crying him mercy, with many impudent and shallow excuses, desired him to reveale the meaning of those words, and what he should understand by Bonum & Commodum.

The Scholler (with a sober and modest countenance) made answere; That he had bin over-much abused, which (neverthelesse) he tooke not so impaciently, but hee had already both forgot and forgiven it, with promise of comfort in this his extraordinary distraction, and greefe of minde. When he had perused the Suffraganes Letter, well observing the blushlesse ignorance of the Priest: seeming (by outward appearance) to take it strangely, he cryed out alowd, saying; In the name of Vertue, what may be this mans meaning? How? (quoth the Priest) What manner of demand do you make? Alas, replyed the Scholler, you have but one poore Asse, which I know you love deerely, and yet you must stew his genitories very daintily, for your Patron will have no other meat to his dinner. The genitories of mine Asse, answered the Priest? Passion of me, who then shall carrie my Corne to the Mill? There is no remedie, sayde the Scholler, for he hath so set it downe for an absolute resolution.