The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Collected Works in Verse and Prose of

William Butler Yeats, Vol. 3 (of 8), by William Butler Yeats

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Collected Works in Verse and Prose of William Butler Yeats, Vol. 3 (of 8)

The Countess Cathleen. The Land of Heart's Desire. The

Unicorn from the Stars

Author: William Butler Yeats

Release Date: August 5, 2015 [EBook #49610]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WORKS OF W B YEATS, VOL 3 ***

Produced by Emmy, mollypit and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

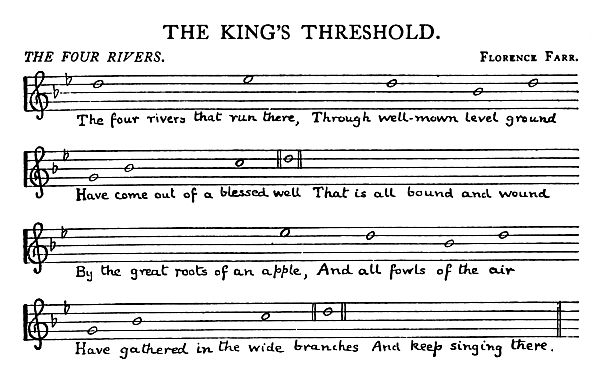

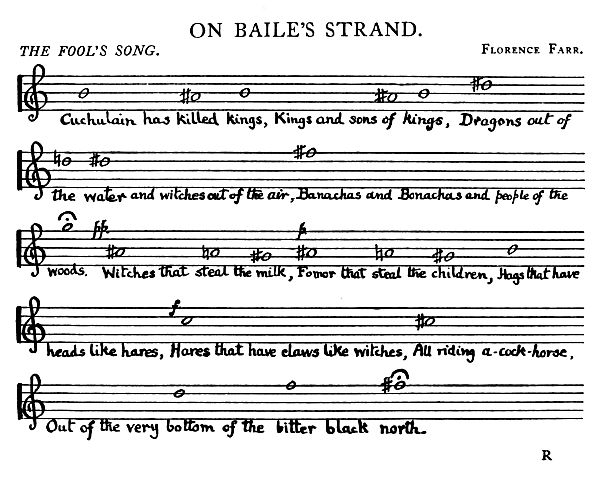

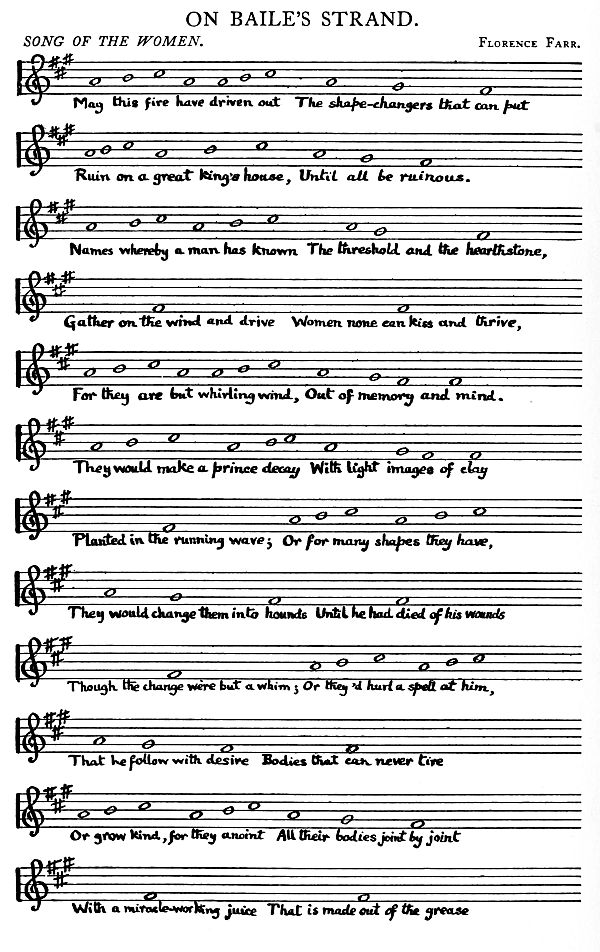

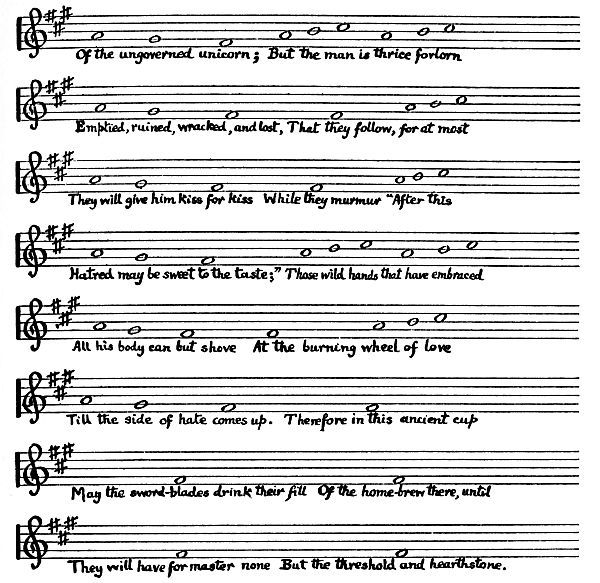

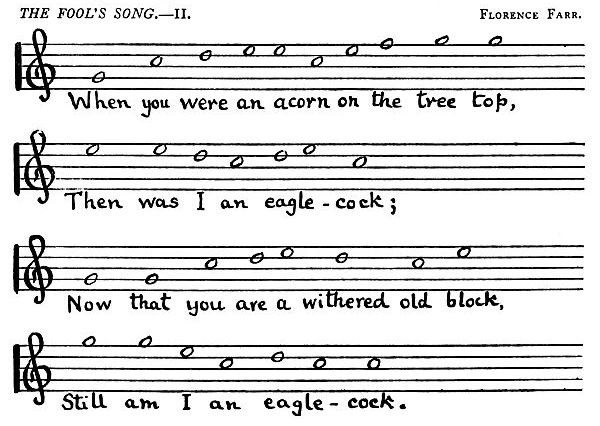

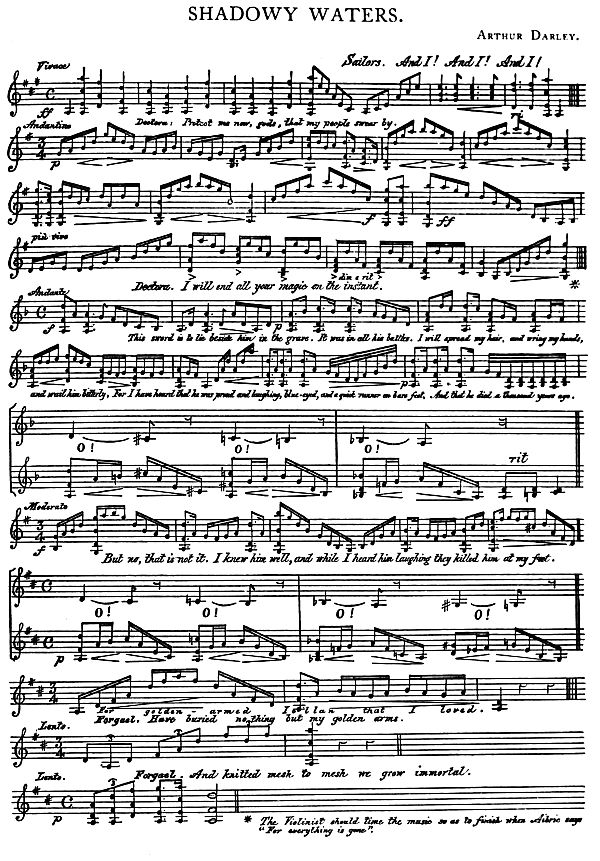

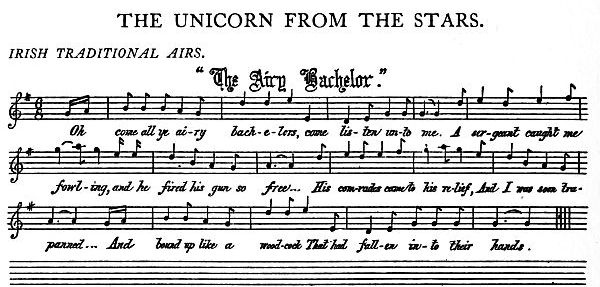

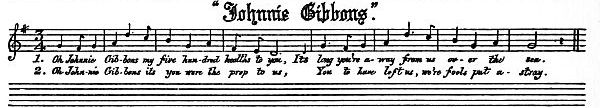

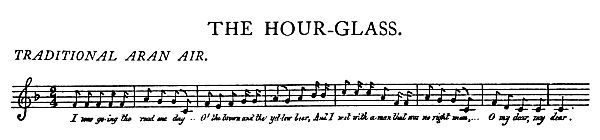

Internet Archive) Music transcribed by Linda Cantoni.

| PAGE | |

| THE COUNTESS CATHLEEN | 1 |

| THE LAND OF HEART’S DESIRE | 89 |

| THE UNICORN FROM THE STARS, | |

| BY LADY GREGORY AND W. B. YEATS | 121 |

| APPENDIX: | |

| THE COUNTESS CATHLEEN | 209 |

| NOTES | 214 |

The scene is laid in Ireland, and in old times.

[Going over to the little shrine.]

[Picking the bough from the table.]

[Taking a stone bottle out of his bag.]

[Bringing drinking-cups.]

[Enter SERVANT.]

CATHLEEN [within].

CATHLEEN [coming to chapel door].

[Going to the window.]

[The FIRST MERCHANT goes to the door and stands beside him.]

FIRST MERCHANT [reading].

The scene is laid in the Barony of Kilmacowen, in the County of Sligo, and the characters are supposed to speak in Gaelic. They wear the costume of a century ago.

MAIRE BRUIN [in a dreamy voice].

MAIRE [to SHAWN BRUIN].

THE CHILD [to MAIRE].

| Father John | ||

| Thomas Hearne, | a coachbuilder | |

| Andrew Hearne, | his brother | |

| Martin Hearne, | his nephew | |

| Johnny Bacach | - beggars | |

| Paudeen | ||

| Biddy Lally | ||

| Nanny |

I have prayed over Martin. I have prayed a long time, but there is no move in him yet.

You are giving yourself too much trouble, Father. It’s as good for you to leave him alone till the doctor’s bottle will come. If there is any cure at all for what is on him, it is likely the doctor will have it.

I think it is not doctor’s medicine will help him in this case.[124]

It will, it will. The doctor has his business learned well. If Andrew had gone to him the time I bade him and had not turned again to bring yourself to the house, it is likely Martin would be walking at this time. I am loth to trouble you, Father, when the business is not of your own sort. Any doctor at all should be able and well able to cure the falling sickness.

It is not any common sickness that is on him now.

I thought at the first it was gone to sleep he was. But when shaking him and roaring at him failed to rouse him, I knew well it was the falling sickness. Believe me, the doctor will reach it with his drugs.

Nothing but prayer can reach a soul that is so far beyond the world as his soul is at this moment.

You are not saying that the life is gone out of him![125]

No, no, his life is in no danger. But where he himself, the spirit, the soul, is gone, I cannot say. It has gone beyond our imaginings. He is fallen into a trance.

He used to be queer as a child, going asleep in the fields, and coming back with talk of white horses he saw, and bright people like angels or whatever they were. But I mended that. I taught him to recognise stones beyond angels with a few strokes of a rod. I would never give in to visions or to trances.

We who hold the faith have no right to speak against trance or vision. Saint Elizabeth had them, Saint Benedict, Saint Anthony, Saint Columcille. Saint Catherine of Siena often lay a long time as if dead.

That might be so in the olden time, but those things are gone out of the world now. Those that do their work fair and honest have no occasion to let the mind go rambling. What would send my nephew, Martin Hearne, into a trance, supposing trances to be in it, and he[126] rubbing the gold on the lion and unicorn that he had taken in hand to make a good job of for the top of the coach?

It is likely it was that sent him off. The flashing of light upon it would be enough to throw one that had a disposition to it into a trance. There was a very saintly man, though he was not of our church; he wrote a great book called Mysterium Magnum was seven days in a trance. Truth, or whatever truth he found, fell upon him like a bursting shower, and he a poor tradesman at his work. It was a ray of sunlight on a pewter vessel that was the beginning of all. [Goes to the door and looks in.] There is no stir in him yet. It is either the best thing or the worst thing can happen to anyone, that is happening to him now.

And what in the living world can happen to a man that is asleep on his bed?

There are some would answer you that it is to those who are awake that nothing happens, and it is they that know nothing. He is gone where all have gone for supreme truth.[127]

Well, maybe so. But work must go on and coachbuilding must go on, and they will not go on the time there is too much attention given to dreams. A dream is a sort of a shadow, no profit in it to anyone at all. A coach, now, is a real thing and a thing that will last for generations and be made use of to the last, and maybe turn to be a hen-roost at its latter end.

I think Andrew told me it was a dream of Martin’s that led to the making of that coach.

Well, I believe he saw gold in some dream, and it led him to want to make some golden thing, and coaches being the handiest, nothing would do him till he put the most of his fortune into the making of this golden coach. It turned out better than I thought, for some of the lawyers came looking at it at Assize time, and through them it was heard of at Dublin Castle . . . and who now has it ordered but the Lord Lieutenant! [FATHER JOHN nods.] Ready it must be and sent off it must be by the end of the month. It is likely King George will be[128] visiting Dublin, and it is he himself will be sitting in it yet.

Martin has been working hard at it, I know.

You never saw a man work the way he did, day and night, near ever since the time six months ago he first came home from France.

I never thought he would be so good at a trade. I thought his mind was only set on books.

He should be thankful to myself for that. Any person I will take in hand, I make a clean job of them the same as I would make of any other thing in my yard—coach, half-coach, hackney-coach, ass-car, common-car, post-chaise, calash, chariot on two wheels, on four wheels. Each one has the shape Thomas Hearne put on it, and it in his hands; and what I can do with wood and iron, why would I not be able to do it with flesh and blood, and it in a way my own?

Indeed, I know you did your best for Martin.[129]

Every best. Checked him, taught him the trade, sent him to the monastery in France for to learn the language and to see the wide world; but who should know that if you did not know it, Father John, and I doing it according to your own advice?

I thought his nature needed spiritual guidance and teaching, the best that could be found.

I thought myself it was best for him to be away for a while. There are too many wild lads about this place. He to have stopped here, he might have taken some fancies, and got into some trouble, going against the Government maybe the same as Johnny Gibbons that is at this time an outlaw, having a price upon his head.

That is so. That imagination of his might have taken fire here at home. It was better putting him with the Brothers, to turn it to imaginings of heaven.

Well, I will soon have a good hardy tradesman made of him now that will live quiet and[130] rear a family, and be maybe appointed coachbuilder to the Royal Family at the last.

I see your brother Andrew coming back from the doctor; he is stopping to talk with a troop of beggars that are sitting by the side of the road.

There, now, is another that I have shaped. Andrew used to be a bit wild in his talk and in his ways, wanting to go rambling, not content to settle in the place where he was reared. But I kept a guard over him; I watched the time poverty gave him a nip, and then I settled him into the business. He never was so good a worker as Martin, he is too fond of wasting his time talking vanities. But he is middling handy, and he is always steady and civil to customers. I have no complaint worth while to be making this last twenty years against Andrew.

Beggars there outside going the road to the Kinvara fair. They were saying there is news that Johnny Gibbons is coming back from France on the quiet; the king’s soldiers are watching the ports for him.[131]

Let you keep now, Andrew, to the business you have in hand. Will the doctor be coming himself or did he send a bottle that will cure Martin?

The doctor can’t come, for he’s down with the lumbago in the back. He questioned me as to what ailed Martin, and he got a book to go looking for a cure, and he began telling me things out of it, but I said I could not be carrying things of that sort in my head. He gave me the book then, and he has marks put in it for the places where the cures are . . . wait now. . . . [Reads] ‘Compound medicines are usually taken inwardly, or outwardly applied; inwardly taken, they should be either liquid or solid; outwardly, they should be fomentations or sponges wet in some decoctions.’

He had a right to have written it out himself upon a paper. Where is the use of all that?

I think I moved the mark maybe . . . here, now, is the part he was reading to me himself. . . . ‘The remedies for diseases belonging to[132] the skins next the brain, headache, vertigo, cramp, convulsions, palsy, incubus, apoplexy, falling sickness.’

It is what I bid you to tell him that it was the falling sickness.

O, my dear, look at all the marks gone out of it! Wait, now, I partly remember what he said . . . a blister he spoke of . . . or to be smelling hartshorn . . . or the sneezing powder . . . or if all fails, to try letting the blood.

All this has nothing to do with the real case. It is all waste of time.

That is what I was thinking myself, Father. Sure it was I was the first to call out to you when I saw you coming down from the hill-side, and to bring you in to see what could you do. I would have more trust in your means than in any doctor’s learning. And in case you might fail to cure him, I have a cure myself I heard from my grandmother—God rest her soul!—and she told me she never knew it to fail. A person to have the falling sickness, to cut the top of his nails and a small share of the hair of[133] his head, and to put it down on the floor, and to take a harry-pin and drive it down with that into the floor and to leave it there. ‘That is the cure will never fail,’ she said, ‘to rise up any person at all having the falling sickness.’

I will go back to the hill-side, I will go back to the hill-side; but no, no, I must do what I can. I will go again, I will wrestle, I will strive my best to call him back with prayer.

It is queer Father John is sometimes, and very queer. There are times when you would say that he believes in nothing at all.

If you wanted a priest, why did you not get our own parish priest that is a sensible man, and a man that you would know what his thoughts are? You know well the bishop should have something against Father John to have left him through the years in that poor mountainy place, minding the few unfortunate people that were left out of the last famine. A man of his learning to be going in rags the way he is, there must be some good cause for that.[134]

I had all that in mind and I bringing him. But I thought he would have done more for Martin than what he is doing. To read a Mass over him I thought he would, and to be convulsed in the reading it, and some strange thing to have gone out with a great noise through the doorway.

It would give no good name to the place such a thing to be happening in it. It is well enough for labouring-men and for half-acre men. It would be no credit at all such a thing to be heard of in this house, that is for coachbuilding the capital of the county.

If it is from the devil this sickness comes, it would be best to put it out whatever way it would be put out. But there might no bad thing be on the lad at all. It is likely he was with wild companions abroad, and that knocking about might have shaken his health. I was that way myself one time.

Father John said that it was some sort of a vision or a trance, but I would give no heed[135] to what he would say. It is his trade to see more than other people would see, the same as I myself might be seeing a split in a leather car hood that no other person would find out at all.

If it is the falling sickness is on him, I have no objection to that—a plain, straight sickness that was cast as a punishment on the unbelieving Jews. It is a thing that might attack one of a family, and one of another family, and not to come upon their kindred at all. A person to have it, all you have to do is not to go between him and the wind, or fire, or water. But I am in dread trance is a thing might run through the house the same as the cholera morbus.

In my belief there is no such thing as a trance. Letting on people do be to make the world wonder the time they think well to rise up. To keep them to their work is best, and not to pay much attention to them at all.

I would not like trances to be coming on myself. I leave it in my will if I die without cause, a holly-stake to be run through my heart[136] the way I will lie easy after burial, and not turn my face downwards in my coffin. I tell you I leave it on you in my will.

Leave thinking of your own comforts, Andrew, and give your mind to the business. Did the smith put the irons yet on to the shafts of this coach?

I will go see did he.

Do so, and see did he make a good job of it. Let the shafts be sound and solid if they are to be studded with gold.

They are, and the steps along with them—glass sides for the people to be looking in at the grandeur of the satin within—the lion and the unicorn crowning all. It was a great thought Martin had the time he thought of making this coach!

It is best for me to go see the smith myself and leave it to no other one. You can be attending to that ass-car out in the yard wants a new tyre in the wheel—out in the rear of the[137] yard it is. [They go to door.] To pay attention to every small thing, and to fill up every minute of time shaping whatever you have to do, that is the way to build up a business.

They are gone out now—the air is fresher here in the workshop—you can sit here for a while. You are now fully awake, you have been in some sort of a trance or a sleep.

Who was it that pulled at me? Who brought me back?

It is I, Father John, did it. I prayed a long time over you and brought you back.

You, Father John, to be so unkind! O leave me, leave me alone!

You are in your dream still.

It was no dream, it was real. Do you not smell the broken fruit—the grapes? the room is full of the smell.[138]

Tell me what you have seen, where you have been?

There were horses—white horses rushing by, with white shining riders—there was a horse without a rider, and someone caught me up and put me upon him and we rode away, with the wind, like the wind—

That is a common imagining. I know many poor persons have seen that.

We went on, on, on. We came to a sweet-smelling garden with a gate to it, and there were wheatfields in full ear around, and there were vineyards like I saw in France, and the grapes in bunches. I thought it to be one of the townlands of heaven. Then I saw the horses we were on had changed to unicorns, and they began trampling the grapes and breaking them. I tried to stop them but I could not.

That is strange, that is strange. What is it that brings to mind? I heard it in some place, monoceros de astris, the unicorn from the stars.[139]

They tore down the wheat and trampled it on stones, and then they tore down what were left of grapes and crushed and bruised and trampled them. I smelt the wine, it was flowing on every side—then everything grew vague. I cannot remember clearly, everything was silent; the trampling now stopped, we were all waiting for some command. Oh! was it given! I was trying to hear it; there was someone dragging, dragging me away from that. I am sure there was a command given, and there was a great burst of laughter. What was it? What was the command? Everything seemed to tremble round me.

Did you awake then?

I do not think I did, it all changed—it was terrible, wonderful! I saw the unicorns trampling, trampling, but not in the wine troughs. Oh, I forget! Why did you waken me?

I did not touch you. Who knows what hands pulled you away? I prayed, that was all I did. I prayed very hard that you might[140] awake. If I had not, you might have died. I wonder what it all meant? The unicorns—what did the French monk tell me?—strength they meant, virginal strength, a rushing, lasting, tireless strength.

They were strong. Oh, they made a great noise with their trampling.

And the grapes, what did they mean? It puts me in mind of the psalm, Et calix meus inebrians quam præclarus est. It was a strange vision, a very strange vision, a very strange vision.

How can I get back to that place?

You must not go back, you must not think of doing that. That life of vision, of contemplation, is a terrible life, for it has far more of temptation in it than the common life. Perhaps it would have been best for you to stay under rules in the monastery.

I could not see anything so clearly there. It is back here in my own place the visions come, in the place where shining people used to laugh around me, and I a little lad in a bib.[141]

You cannot know but it was from the Prince of this world the vision came. How can one ever know unless one follows the discipline of the Church? Some spiritual director, some wise learned man, that is what you want. I do not know enough. What am I but a poor banished priest, with my learning forgotten, my books never handled and spotted with the damp!

I will go out into the fields where you cannot come to me to awake me. I will see that townland again; I will hear that command. I cannot wait, I must know what happened, I must bring that command to mind again.

You must have patience as the saints had it. You are taking your own way. If there is a command from God for you, you must wait His good time to receive it.

Must I live here forty years, fifty years . . . to grow as old as my uncles, seeing nothing but common things, doing work . . . some foolish work?[142]

Here they are coming; it is time for me to go. I must think and I must pray. My mind is troubled about you. [To THOMAS as he and ANDREW come in.] Here he is; be very kind to him for he has still the weakness of a little child.

Are you well of the fit, lad?

It was no fit. I was away—for awhile—no, you will not believe me if I tell you.

I would believe it, Martin. I used to have very long sleeps myself and very queer dreams.

You had, till I cured you, taking you in hand and binding you to the hours of the clock. The cure that will cure yourself, Martin, and will waken you, is to put the whole of your mind on to your golden coach; to take it in hand and to finish it out of face.

Not just now. I want to think—to try and remember what I saw, something that I heard, that I was told to do.[143]

No, but put it out of your mind. There is no man doing business that can keep two things in his head. A Sunday or a holy-day, now, you might go see a good hurling or a thing of the kind, but to be spreading out your mind on anything outside of the workshop on common days, all coachbuilding would come to an end.

I don’t think it is building I want to do. I don’t think that is what was in the command.

It is too late to be saying that, the time you have put the most of your fortune in the business. Set yourself now to finish your job, and when it is ended maybe I won’t begrudge you going with the coach as far as Dublin.

That is it, that will satisfy him. I had a great desire myself, and I young, to go travelling the roads as far as Dublin. The roads are the great things, they never come to an end. They are the same as the serpent having his tail swallowed in his own mouth.

It was not wandering I was called to. What was it? what was it?[144]

What you are called to, and what everyone having no great estate is called to, is to work. Sure the world itself could not go on without work.

I wonder if that is the great thing, to make the world go on? No, I don’t think that is the great thing—what does the Munster poet call it?—‘this crowded slippery coach-loving world.’ I don’t think I was told to work for that.

I often thought that myself. It is a pity the stock of the Hearnes to be asked to do any work at all.

Rouse yourself, Martin, and don’t be talking the way a fool talks. You started making that golden coach, and you were set upon it, and you had me tormented about it. You have yourself wore out working at it, and planning it, and thinking of it, and at the end of the race, when you have the winning-post in sight, and horses hired for to bring it to Dublin Castle, you go falling into sleeps and blathering about dreams, and we run to a great danger of letting the profit and the sale go by. Sit down on the bench now, and lay your hands to the work.[145]

I will try. I wonder why I ever wanted to make it; it was no good dream set me doing that. [He takes up wheel.] What is there in a wooden wheel to take pleasure in it? Gilding it outside makes it no different.

That is right, now. You had some good plan for making the axle run smooth.

It is no use. [Angrily.] Why did you send the priest to awake me? My soul is my own and my mind is my own. I will send them to where I like. You have no authority over my thoughts.

That is no way to be speaking to me. I am head of this business. Nephew, or no nephew, I will have no one come cold or unwilling to the work.

I had better go; I am of no use to you. I am going—I must be alone—I will forget if I am not alone. Give me what is left of my money and I will go out of this.[146]

There is what is left of your money! The rest of it you have spent on the coach. If you want to go, go, and I will not have to be annoyed with you from this out.

Come now with me, Thomas. The boy is foolish, but it will soon pass over. He has not my sense to be giving attention to what you will say. Come along now, leave him for awhile; leave him to me I say, it is I will get inside his mind.

I think it was some shining thing I saw. What was it?

Listen to me, Martin.

Go away, no more talking; leave me alone.

O, but wait. I understand you. Thomas doesn’t understand your thoughts, but I understand[147] them. Wasn’t I telling you I was just like you once?

Like me? Did you ever see the other things, the things beyond?

I did. It is not the four walls of the house keep me content. Thomas doesn’t know. Oh, no, he doesn’t know.

No, he has no vision.

He has not, nor any sort of a heart for a frolic.

He has never heard the laughter and the music beyond.

He has not, nor the music of my own little flute. I have it hidden in the thatch outside.

Does the body slip from you as it does from me? They have not shut your window into eternity?

Thomas never shut a window I could not get through. I knew you were one of my own sort. When I am sluggish in the morning,[148] Thomas says, ‘Poor Andrew is getting old.’ That is all he knows. The way to keep young is to do the things youngsters do. Twenty years I have been slipping away, and he never found me out yet!

That is what they call ecstasy, but there is no word that can tell out very plain what it means. That freeing of the mind from its thoughts, those wonders we know when we put them into words; the words seem as little like them as blackberries are like the moon and sun.

I found that myself the time they knew me to be wild, and used to be asking me to say what pleasure did I find in cards, and women, and drink.

You might help me to remember that vision I had this morning, to understand it. The memory of it has slipped from me. Wait, it is coming back, little by little. I know that I saw the unicorns trampling, and then a figure, a many-changing figure, holding some bright thing. I knew something was going to happen or to be said, something that would make my whole life strong and beautiful like the rushing of the unicorns, and then, and then—[149]

A poor person I am, without food, without a way, without portion, without costs, without a person or a stranger, without means, without hope, without health, without warmth—

It is that troop of beggars. Bringing their tricks and their thieveries they are to the Kinvara Fair.

There is no quiet—come to the other room. I am trying to remember.

They are a bad-looking fleet. I have a mind to drive them away, giving them a charity.

Drive them away or come away from their voices.

I put under the power of my prayer

Whisht! He is entering by the window!

That I may never sin, but the place is empty.

Go in and see what can you make a grab at.

That every blessing I gave may be turned to a curse on them that left the place so bare! [He turns things over.] I might chance something in this chest if it was open.

Hurry on, now, you limping crabfish you! We can’t be stopping here while you’ll boil stirabout!

Look at this, now, look!

Destruction on us all!

That is it! O, I remember. That is what[151] happened. That is the command. Who was it sent you here with that command?

It was misery sent me in, and starvation, and the hard ways of the world.

It was that, my poor child, and my one son only. Show mercy to him now and he after leaving gaol this morning.

I was trying to remember it—when he spoke that word it all came back to me. I saw a bright many-changing figure; it was holding up a shining vessel [holds up arms]; then the vessel fell and was broken with a great crash; then I saw the unicorns trampling it. They were breaking the world to pieces—when I saw the cracks coming I shouted for joy! And I heard the command ‘Destroy, destroy, destruction is the life-giver! destroy!’

What will we do with him? He was thinking to rob you of your gold.

How could I forget it or mistake it? It has all come upon me now; the reasons of it all, like a flood, like a flooded river.[152]

It was the hunger brought me in and the drouth.

Were you given any other message? Did you see the unicorns?

I saw nothing and heard nothing; near dead I am with the fright I got and with the hardship of the gaol.

To destroy, to overthrow all that comes between us and God, between us and that shining country. To break the wall, Andrew, to break the thing—whatever it is that comes between, but where to begin—

What is it you are talking about?

It may be that this man is the beginning. He has been sent—the poor, they have nothing, and so they can see heaven as we cannot. He and his comrades will understand me. But how to give all men high hearts that they may all understand?[153]

It’s the juice of the grey barley will do that.

To rise everybody’s heart, is it? Is it that was your meaning all the time? If you will take the blame of it all, I’ll do what you want. Give me the bag of money then. [He takes it up.] O, I’ve a heart like your own. I’ll lift the world, too. The people will be running from all parts. O, it will be a great day in this district.

Will I go with you?

No, you must stay here; we have things to do and to plan.

Destroyed we all are with the hunger and the drouth.

Go, then, get food and drink, whatever is wanted to give you strength and courage. Gather your people together here, bring them all in. We have a great thing to do. I have to begin—I want to tell it to the whole world. Bring them in, bring them in, I will make the house ready.

Come in, come in, I have got the house ready. Here is bread and meat—everybody is welcome.

Martin, I have come back. There is something I want to say to you.

You are welcome, there are others coming. They are not of your sort, but all are welcome.

I have remembered suddenly something that I read when I was in the seminary.

You seem very tired.[155]

I had almost got back to my own place when I thought of it. I have run part of the way. It is very important; it is about the trance that you have been in. When one is inspired from above, either in trance or in contemplation, one remembers afterwards all that one has seen and read. I think there must be something about it in St. Thomas. I know that I have read a long passage about it years ago. But, Martin, there is another kind of inspiration, or rather an obsession or possession. A diabolical power comes into one’s body, or overshadows it. Those whose bodies are taken hold of in this way, jugglers, and witches, and the like, can often tell what is happening in distant places, or what is going to happen, but when they come out of that state they remember nothing. I think you said—

That I could not remember.

You remembered something, but not all. Nature is a great sleep; there are dangerous and evil spirits in her dreams, but God is above Nature. She is a darkness, but He makes everything clear; He is light.[156]

All is clear now. I remember all, or all that matters to me. A poor man brought me a word, and I know what I have to do.

Ah, I understand, words were put into his mouth. I have read of such things. God sometimes uses some common man as his messenger.

You may have passed the man who brought it on the road. He left me but now.

Very likely, very likely, that is the way it happened. Some plain, unnoticed man has sometimes been sent with a command.

I saw the unicorns trampling in my dream. They were breaking the world. I am to destroy, destruction was the word the messenger spoke.

To destroy?

To bring again the old disturbed exalted life, the old splendour.[157]

You are not the first that dream has come to. [Gets up, and walks up and down.] It has been wandering here and there, calling now to this man, now to that other. It is a terrible dream.

Father John, you have had the same thought.

Men were holy then, there were saints everywhere. There was reverence; but now it is all work, business, how to live a long time. Ah, if one could change it all in a minute, even by war and violence! There is a cell where Saint Ciaran used to pray; if one could bring that time again!

Do not deceive me. You have had the command.

Why are you questioning me? You are asking me things that I have told to no one but my confessor.

We must gather the crowds together, you and I.[158]

I have dreamed your dream, it was long ago. I had your vision.

And what happened?

It was stopped; that was an end. I was sent to the lonely parish where I am, where there was no one I could lead astray. They have left me there. We must have patience; the world was destroyed by water, it has yet to be consumed by fire.

Why should we be patient? To live seventy years, and others to come after us and live seventy years it may be; and so from age to age, and all the while the old splendour dying more and more.

Martin says truth, and he says it well. Planing the side of a cart or a shaft, is that life? It is not. Sitting at a desk writing letters to the man that wants a coach, or to the man that won’t pay for the one he has got,[159] is that life, I ask you? Thomas arguing at you and putting you down—‘Andrew, dear Andrew, did you put the tyre on that wheel yet?’ Is that life? Not, it is not. I ask you all, what do you remember when you are dead? It’s the sweet cup in the corner of the widow’s drinking-house that you remember. Ha, ha, listen to that shouting! That is what the lads in the village will remember to the last day they live.

Why are they shouting? What have you told them?

Never you mind; you left that to me. You bade me to lift their hearts and I did lift them. There is not one among them but will have his head like a blazing tar-barrel before morning. What did your friend the beggar say? The juice of the grey barley, he said.

You accursed villain! You have made them drunk!

Not at all, but lifting them to the stars. That is what Martin bade me to do, and there is no one can say I did not do it.[160]

It’s not him, it’s that one! [Points at MARTIN.

Are you bringing this devil’s work in at the very door? Go out of this, I say! get out! Take these others with you!

No, no; I asked them in, they must not be turned out. They are my guests.

Drive them out of your uncle’s house!

Come, Father, it is better for you to go. Go back to your own place. I have taken the command. It is better perhaps for you that you did not take it.

It is well for that old lad he didn’t come between ourselves and our luck. Himself to be after his meal, and ourselves staggering with the hunger! It would be right to have flayed him and to have made bags of his skin.[161]

What a hurry you are in to get your enough! Look at the grease on your frock yet, with the dint of the dabs you put in your pocket! Doing cures and foretellings is it? You starved pot-picker, you!

That you may be put up to-morrow to take the place of that decent son of yours that had the yard of the gaol wore with walking it till this morning!

If he had, he had a mother to come to, and he would know her when he did see her; and that is what no son of your own could do and he to meet you at the foot of the gallows.

If I did know you, I knew too much of you since the first beginning of my life! What reward did I ever get travelling with you? What store did you give me of cattle or of goods? What provision did I get from you by day or by night but your own bad character to be joined on to my own, and I following at your heels, and your bags tied round about me!

Disgrace and torment on you! Whatever you got from me, it was more than any reward[162] or any bit I ever got from the father you had, or any honourable thing at all, but only the hurt and the harm of the world and its shame!

What would he give you, and you going with him without leave! Crooked and foolish you were always, and you begging by the side of the ditch.

Begging or sharing, the curse of my heart upon you! It’s better off I was before ever I met with you to my cost! What was on me at all that I did not cut a scourge in the wood to put manners and decency on you the time you were not hardened as you are!

Leave talking to me of your rods and your scourges! All you taught me was robbery, and it is on yourself and not on myself the scourges will be laid at the day of the recognition of tricks.

’Faith, the pair of you together is better than Hector fighting before Troy!

Ah, let you be quiet. It is not fighting we are craving, but the easing of the hunger that is on us and of the passion of sleep. Lend me[163] a graineen of tobacco now till I’ll kindle my pipe—a blast of it will take the weight of the road off my heart.

No, but it’s to myself you should give it. I that never smoked a pipe this forty year without saying the tobacco prayer. Let that one say did ever she do that much.

That the pain of your front tooth may be in your back tooth, you to be grabbing my share!

Pup, pup, pup! Don’t be snapping and quarrelling now, and you so well treated in this house. It is strollers like yourselves should be for frolic and for fun. Have you ne’er a good song to sing, a song that will rise all our hearts?

Johnny Bacach is a good singer, it is what he used to be doing in the fairs, if the oakum of the gaol did not give him a hoarseness within the throat.

Give it out so, a good song, a song will put courage and spirit into any man at all.[164]

That’s no good of a song but a melancholy sort of a song. I’d as lief be listening to a saw going through timber. Wait, now, till you will hear myself giving out a tune on the flute.

It is what I am thinking there must be a great dearth and a great scarcity of good comrades in this place, a man like that youngster, having means in his hand, to be bringing ourselves and our rags into the house.

You think yourself very wise, Johnny Bacach. Can you tell me, now, who that man is?[165]

Some decent lad, I suppose, with a good way of living and a mind to send up his name upon the roads.

You that have been gaoled this eight months know little of this countryside. It isn’t a limping stroller like yourself the Boys would let come among them. But I know. I went to the drill a few nights and I skinning kids for the mountainy men. In a quarry beyond the drill is—they have their plans made—it’s the square house of the Brownes is to be made an attack on and plundered. Do you know, now, who is the leader they are waiting for?

How would I know that?

Sure that man could not be Johnny Gibbons that is outlawed!

I asked news of him from the old lad, and I bringing in the drink along with him. ‘Don’t be asking questions,’ says he; ‘take the treat he[166] gives you,’ says he. ‘If a lad that has a high heart has a mind to rouse the neighbours,’ says he, ‘and to stretch out his hand to all that pass the road, it is in France he learned it,’ says he, ‘the place he is but lately come from, and where the wine does be standing open in tubs. Take your treat when you get it,’ says he, ‘and make no delay or all might be discovered and put an end to.’

He came over the sea from France! It is Johnny Gibbons, surely, but it seems to me they were calling him by some other name.

A man on his keeping might go by a hundred names. Would he be telling it out to us that he never saw before, and we with that clutch of chattering women along with us? Here he is coming now. Wait till you see is he the lad I think him to be.

I will make my banner, I will paint the unicorn on it. Give me that bit of canvas, there is paint over here. We will get no help from the settled men—we will call to the lawbreakers, the tinkers, the sievemakers, the sheepstealers.

That sounds to be a queer name of an army. Ribbons I can understand, Whiteboys, Rightboys, Threshers, and Peep o’ Day, but Unicorns I never heard of before.

It is not a queer name but a very good name. [Takes up lion and unicorn.] It is often you saw that before you in the dock. There is the unicorn with the one horn, and what it is he is going against? The lion of course. When he has the lion destroyed, the crown must fall and be shivered. Can’t you see it is the League of the Unicorns is the league that will fight and destroy the power of England and King George?

It is with that banner we will march and the lads in the quarry with us, it is they will have the welcome before him! It won’t be long till we’ll be attacking the Square House! Arms there are in it, riches that would smother the world, rooms full of guineas we will put wax on our shoes walking them; the horses themselves shod with no less than silver!

There it is ready! We are very few now, but the army of the Unicorns will be a great[168] army! [To JOHNNY.] Why have you brought me the message? Can you remember any more? Has anything more come to you? You have been drinking, the clouds upon your mind have been destroyed. . . . Can you see anything or hear anything that is beyond the world?

I can not. I don’t know what do you want me to tell you at all?

I want to begin the destruction, but I don’t know where to begin . . . you do not hear any other voice?

I do not. I have nothing at all to do with Freemasons or witchcraft.

It is Biddy Lally has to do with witchcraft. It is often she threw the cups and gave out prophecies the same as Columcille.

You are one of the knowledgeable women. You can tell me where it is best to begin, and what will happen in the end.

I will foretell nothing at all. I rose out of it this good while, with the stiffness and the swelling it brought upon my joints.[169]

If you have foreknowledge you have no right to keep silent. If you do not help me I may go to work in the wrong way. I know I have to destroy, but when I ask myself what I am to begin with, I am full of uncertainty.

Here now are the cups handy and the leavings in them.

Throw a bit of white money into the four corners of the house.

There! [Throwing it.]

There can be nothing told without silver. It is not myself will have the profit of it. Along with that I will be forced to throw out gold.

There is a guinea for you. Tell me what comes before your eyes.

What is it you are wanting to have news of?

Of what I have to go out against at the beginning . . . there is so much . . . the whole world it may be.[170]

You have no care for yourself. You have been across the sea, you are not long back. You are coming within the best day of your life.

What is it? What is it I have to do?

I see a great smoke, I see burning . . . there is a great smoke overhead.

That means we have to burn away a great deal that men have piled up upon the earth. We must bring men once more to the wildness of the clean green earth.

Herbs for my healing, the big herb and the little herb, it is true enough they get their great strength out of the earth.

Who was it the green sod of Ireland belonged to in the olden times? Wasn’t it to the ancient race it belonged? And who has possession of it now but the race that came robbing over the sea? The meaning of that is to destroy the big houses and the towns, and the fields to be given back to the ancient race.[171]

That is it. You don’t put it as I do, but what matter? Battle is all.

Columcille said, the four corners to be burned, and then the middle of the field to be burned. I tell you it was Columcille’s prophecy said that.

Iron handcuffs I see and a rope and a gallows, and it maybe is not for yourself I see it, but for some I have acquaintance with a good way back.

That means the law. We must destroy the law. That was the first sin, the first mouthful of the apple.

So it was, so it was. The law is the worst loss. The ancient law was for the benefit of all. It is the law of the English is the only sin.

When there were no laws men warred on one another and man to man, not with machines made in towns as they do now, and they grew hard and strong in body. They were altogether alive like him that made them in his image, like people in that unfallen country. But presently[172] they thought it better to be safe, as if safety mattered or anything but the exaltation of the heart, and to have eyes that danger had made grave and piercing. We must overthrow the laws and banish them.

It is what I say, to put out the laws is to put out the whole nation of the English. Laws for themselves they made for their own profit, and left us nothing at all, no more than a dog or a sow.

An old priest I see, and I would not say is he the one was here or another. Vexed and troubled he is, kneeling fretting and ever-fretting in some lonesome ruined place.

I thought it would come to that. Yes, the Church too—that is to be destroyed. Once men fought with their desires and their fears, with all that they call their sins, unhelped, and their souls became hard and strong. When we have brought back the clean earth and destroyed the law and the Church all life will become like a flame of fire, like a burning eye . . . Oh, how to find words for it all . . . all that is not life will pass away.[173]

It is Luther’s Church he means, and the humpbacked discourse of Seaghan Calvin’s Bible. So we will break it, and make an end of it.

We will go out against the world and break it and unmake it. [Rising.] We are the army of the Unicorn from the Stars! We will trample it to pieces.—We will consume the world, we will burn it away—Father John said the world has yet to be consumed by fire. Bring me fire.

Here is Thomas. Hide—let you hide.

Come with me, Martin. There is terrible work going on in the town! There is mischief gone abroad. Very strange things are happening!

What are you talking of? What has happened?

Come along, I say, it must be put a stop to. We must call to every decent man. It is as if the devil himself had gone through the town on a blast and set every drinking-house open![174]

I wonder how that has happened. Can it have anything to do with Andrew’s plan?

Are you giving no heed to what I’m saying? There is not a man, I tell you, in the parish and beyond the parish but has left the work he was doing whether in the field or in the mill.

Then all work has come to an end? Perhaps that was a good thought of Andrew’s.

There is not a man has come to sensible years that is not drunk or drinking! My own labourers and my own serving-men are sitting on counters and on barrels! I give you my word, the smell of the spirits and the porter and the shouting and the cheering within, made the hair to rise up on my scalp.

And yet there is not one of them that does not feel that he could bridle the four winds.

You are drunk too. I never thought you had a fancy for it.[175]

It is hard for you to understand. You have worked all your life. You have said to yourself every morning, ‘What is to be done to-day?’ and when you are tired out you have thought of the next day’s work. If you gave yourself an hour’s idleness, it was but that you might work the better. Yet it is only when one has put work away that one begins to live.

It is those French wines that did it.

I have been beyond the earth. In Paradise, in that happy townland, I have seen the shining people. They were all doing one thing or another, but not one of them was at work. All that they did was but the overflowing of their idleness, and their days were a dance bred of the secret frenzy of their hearts, or a battle where the sword made a sound that was like laughter.

You went away sober from out of my hands; they had a right to have minded you better.

No man can be alive, and what is paradise but fulness of life, if whatever he sets his hand[176] to in the daylight cannot carry him from exaltation to exaltation, and if he does not rise into the frenzy of contemplation in the night silence. Events that are not begotten in joy are misbegotten and darken the world, and nothing is begotten in joy if the joy of a thousand years has not been crushed into a moment.

And I offered to let you go to Dublin in the coach!

Give me the lamp. The lamp has not yet been lighted and the world is to be consumed!

Is it here you are, Andrew? What are these beggars doing? Was this door thrown open too? Why did you not keep order? I will go for the constables to help us!

You will not find them to help you. They were scattering themselves through the drinking-houses of the town, and why wouldn’t they?

Are you drunk too? You are worse than Martin. You are a disgrace![177]

Disgrace yourself! Coming here to be making an attack on me and badgering me and disparaging me! And what about yourself that turned me to be a hypocrite?

What are you saying?

You did, I tell you! Weren’t you always at me to be regular and to be working and to be going through the day and the night without company and to be thinking of nothing but the trade? What did I want with a trade? I got a sight of the fairy gold one time in the mountains. I would have found it again and brought riches from it but for you keeping me so close to the work.

Oh, of all the ungrateful creatures! You know well that I cherished you, leading you to live a decent, respectable life.

You never had respect for the ancient ways. It is after the mother you take it, that was too soft and too lumpish, having too much of the English in her blood. Martin is a Hearne like[178] myself. It is he has the generous heart! It is not Martin would make a hypocrite of me and force me to do night-walking secretly, watching to be back by the setting of the seven stars!

I will turn you out of this, yourself and this filthy troop! I will have them lodged in gaol.

Filthy troop, is it? Mind yourself! The change is coming. The pikes will be up and the traders will go down!

Let me out of this, you villains!

We’ll make a sieve of holes of you, you old bag of treachery!

How well you threatened us with gaol, you skim of a weasel’s milk![179]

You heap of sicknesses! You blinking hangman! That you may never die till you’ll get a blue hag for a wife!

Let him go. [They let THOMAS go, and fall back.] Spread out the banner. The moment has come to begin the war.

Up with the Unicorn and destroy the Lion! Success to Johnny Gibbons and all good men!

Heap all those things together there. Heap those pieces of the coach one upon another. Put that straw under them. It is with this flame I will begin the work of destruction. All nature destroys and laughs.

Destroy your own golden coach!

I am sorry to go a way that you do not like and to do a thing that will vex you. I have been a great trouble to you since I was a child in the house, and I am a great trouble to you yet. It is not my fault. I have been chosen for[180] what I have to do. [Stands up.] I have to free myself first and those that are near me. The love of God is a very terrible thing! [THOMAS tries to stop him, but is prevented by Beggars. MARTIN takes a wisp of straw and lights it.] We will destroy all that can perish! It is only the soul that can suffer no injury. The soul of man is of the imperishable substance of the stars!

Well, you are great heroes and great warriors and great lads altogether, to have put down the Brownes the way you did, yourselves and the Whiteboys of the quarry. To have ransacked the house and have plundered it! Look at the silks and the satins and the grandeurs I brought away! Look at that now! [Holds up a velvet cloak.] It’s a good little jacket for myself will come out of it. It’s the singers will be stopping their songs and the jobbers turning from their cattle in the fairs to be taking a view of the laces of it and the buttons! It’s my far-off cousins will be drawing from far and near!

There was not so much gold in it all as what they were saying there was. Or maybe that fleet of Whiteboys had the place ransacked[182] before we ourselves came in. Bad cess to them that put it in my mind to go gather up the full of my bag of horseshoes out of the forge. Silver they were saying they were, pure white silver; and what are they in the end but only hardened iron! A bad end to them! [Flings away horseshoes.] The time I will go robbing big houses again it will not be in the light of the full moon I will go doing it, that does be causing every common thing to shine out as if for a deceit and a mockery. It’s not shining at all they are at this time, but duck yellow and dark.

To leave the big house blazing after us, it was that crowned all! Two houses to be burned to ashes in the one night. It is likely the servant-girls were rising from the feathers and the cocks crowing from the rafters for seven miles around, taking the flames to be the whitening of the dawn.

It is the lad is stretched beyond you have to be thankful to for that. There was never seen a leader was his equal for spirit and for daring. Making a great scatter of the guards the way he did. Running up roofs and ladders, the fire in his hand, till you’d think he would be apt to strike his head against the stars.[183]

I partly guessed death was near him, and the queer shining look he had in his two eyes, and he throwing sparks east and west through the beams. I wonder now was it some inward wound he got, or did some hardy lad of the Brownes give him a tip on the skull unknownst in the fight? It was I myself found him, and the troop of the Whiteboys gone, and he lying by the side of a wall as weak as if he had knocked a mountain. I failed to waken him trying him with the sharpness of my nails, and his head fell back when I moved it, and I knew him to be spent and gone.

It’s a pity you not to have left him where he was lying and said no word at all to Paudeen or to that son you have, that kept us back from following on, bringing him here to this shelter on sacks and upon poles.

What way could I help letting a screech out of myself, and the life but just gone out of him in the darkness, and not a living Christian by his side but myself and the great God?

It’s on ourselves the vengeance of the red soldiers will fall, they to find us sitting here the[184] same as hares in a tuft. It would be best for us follow after the rest of the army of the Whiteboys.

Whisht! I tell you. The lads are cracked about him. To get but the wind of the word of leaving him, it’s little but they’d knock the head off the two of us. Whisht!

Wouldn’t you say now there was some malice or some venom in the air, that is striking down one after another the whole of the heroes of the Gael?

It makes a person be thinking of the four last ends, death and judgment, heaven and hell. Indeed and indeed my heart lies with him. It is well I knew what man he was under his by-name and his disguise.

It is lost we are now and broken to the end of our days. There is no satisfaction at all but to be destroying the English, and where now will we get so good a leader again? Lay him[185] out fair and straight upon a stone, till I will let loose the secret of my heart keening him!

Is it mould candles you have brought to set around him, Johnny Bacach? It is great riches you should have in your pocket to be going to those lengths and not to be content with dips.

It is lengths I will not be going to the time the life will be gone out of your own body. It is not your corpse I will be wishful to hold in honour the way I hold this corpse in honour.

That’s the way always, there will be grief and quietness in the house if it is a young person has died, but funning and springing and tricking one another if it is an old person’s corpse is in it. There is no compassion at all for the old.

It is he would have got leave for the Gael to be as high as the Gall. Believe me, he was in the prophecies. Let you not be comparing yourself with the like of him.[186]

Why wouldn’t I be comparing myself? Look at all that was against me in the world. Would you be matching me against a man of his sort, that had the people shouting him and that had nothing to do but to die and to go to heaven?

The day you go to heaven that you may never come back alive out of it! But it is not yourself will ever hear the saints hammering at their musics! It is you will be moving through the ages, chains upon you, and you in the form of a dog or a monster. I tell you that one will go through Purgatory as quick as lightning through a thorn-bush.

That’s the way, that the way.

Five white candles. I wouldn’t begrudge them to him indeed. If he had held out and held up it is my belief he would have freed Ireland![187]

Wait till the full light of the day and you’ll see the burying he’ll have. It is not in this place we will be waking him. I’ll make a call to the two hundred Ribbons he was to lead on to the attack on the barracks at Aughanish. They will bring him marching to his grave upon the hill. He had surely some gift from the other world, I wouldn’t say but he had power from the other side.

Well, it was a great night he gave to the village, and it is long till it will be forgotten. I tell you the whole of the neighbours are up against him. There is no one at all this morning to set the mills going. There was no bread baked in the night-time, the horses are not fed in the stalls, the cows are not milked in the sheds. I met no man able to make a curse this night but he put it on my head and on the head of the boy that is lying there before us . . . Is there no sign of life in him at all?

What way would there be a sign of life and the life gone out of him this three hours or more?[188]

He was lying in his sleep for a while yesterday, and he wakened again after another while.

He will not waken, I tell you. I held his hand in my own and it getting cold as if you were pouring on it the coldest cold water, and no running in his blood. He is gone sure enough and the life is gone out of him.

Maybe so, maybe so. It seems to me yesterday his cheeks were bloomy all the while, and now he is as pale as wood ashes. Sure we all must come to it at the last. Well, my white-headed darling, it is you were the bush among us all, and you to be cut down in your prime. Gentle and simple, everyone liked you. It is no narrow heart you had, it is you were for spending and not for getting. It is you made a good wake for yourself, scattering your estate in one night only in beer and in wine for the whole province; and that you may be sitting in the middle of Paradise and in the chair of the Graces!

Amen to that. It’s pity I didn’t think the time I sent for yourself to send the little lad of[189] a messenger looking for a priest to overtake him. It might be in the end the Almighty is the best man for us all!

Sure I sent him on myself to bid the priest to come. Living or dead I would wish to do all that is rightful for the last and the best of my own race and generation.

Is it the priest you are bringing in among us? Where is the sense in that? Aren’t we robbed enough up to this with the expense of the candles and the like?

If it is that poor starved priest he called to that came talking in secret signs to the man that is gone, it is likely he will ask nothing for what he has to do. There is many a priest is a Whiteboy in his heart.

I tell you, if you brought him tied in a bag he would not say an Our Father for you, without you having a half-crown at the top of your fingers.

There is no priest is any good at all but a spoiled priest. A one that would take a drop[190] of drink, it is he would have courage to face the hosts of trouble. Rout them out he would, the same as a shoal of fish from out the weeds. It’s best not to vex a priest, or to run against them at all.

It’s yourself humbled yourself well to one the time you were sick in the gaol and had like to die, and he bade you to give over the throwing of the cups.

Ah, plaster of Paris I gave him. I took to it again and I free upon the roads.

Much good you are doing with it to yourself or any other one. Aren’t you after telling that corpse no later than yesterday that he was coming within the best day of his life?

Whisht, let ye. Here is the priest coming.

It is surely not true that he is dead?

The spirit went from him about the middle hour of the night. We brought him here to[191] this sheltered place. We were loth to leave him without friends.

Where is he?

Lying there stiff and stark. He has a very quiet look as if there was no sin at all or no great trouble upon his mind.

He is not dead.

He is dead. If it was letting on he was, he would not have let that one rob him and search him the way she did.

It has the appearance of death, but it is not death. He is in a trance.

Is it Heaven and Hell he is walking at this time to be bringing back newses of the sinners in pain?

I was thinking myself it might away he was, riding on white horses with the riders of the forths.[192]

He will have great wonders to tell out the time he will rise up from the ground. It is a pity he not to waken at this time and to lead us on to overcome the troop of the English. Sure those that are in a trance get strength, that they can walk on water.

It was Father John wakened him yesterday the time he was lying in the same way. Wasn’t I telling you it was for that I called to him?

Waken him now till they’ll see did I tell any lie in my foretelling. I knew well by the signs, he was coming within the best day of his life.

And not dead at all! We’ll be marching to attack Dublin itself within a week. The horn will blow for him, and all good men will gather to him. Hurry on, Father, and waken him.

I will not waken him. I will not bring him back from where he is.

And how long will it be before he will waken of himself?[193]

Maybe to-day, maybe to-morrow, it is hard to be certain.

If it is away he is he might be away seven years. To be lying like a stump of a tree and using no food and the world not able to knock a word out of him, I know the signs of it well.

We cannot be waiting and watching through seven years. If the business he has started is to be done we have to go on here and now. The time there is any delay, that is the time the Government will get information. Waken him now, Father, and you’ll get the blessing of the generations.

I will not bring him back. God will bring him back in his own good time. For all I know he may be seeing the hidden things of God.

He might slip away in his dream. It is best to raise him up now.

Waken him, Father John. I thought he was surely dead this time, and what way could I go face Thomas through all that is left of my lifetime,[194] after me standing up to face him the way I did? And if I do take a little drop of an odd night, sure I’d be very lonesome if I did not take it. All the world knows it’s not for love of what I drink, but for love of the people that do be with me! Waken him, Father, or maybe I would waken him myself. [Shakes him.]

Lift your hand from touching him. Leave him to himself and to the power of God.

If you will not bring him back why wouldn’t we ourselves do it? Go on now, it is best for you to do it yourself.

I woke him yesterday. He was angry with me, he could not get to the heart of the command.

If he did not, he got a command from myself that satisfied him, and a message.

He did—he took it from you—and how do I know what devil’s message it may have been that brought him into that devil’s work, destruction and drunkenness and burnings! That was not a message from heaven! It was I[195] awoke him, it was I kept him from hearing what was maybe a divine message, a voice of truth, and he heard you speak and he believed the message was brought by you. You have made use of your deceit and his mistaking—you have left him without house or means to support him, you are striving to destroy and to drag him to entire ruin. I will not help you, I would rather see him die in his trance and go into God’s hands than awake him and see him go into hell’s mouth with vagabonds and outcasts like you!

You should have knowledge, Biddy Lally, of the means to bring back a man that is away.

The power of the earth will do it through its herbs, and the power of the air will do it kindling fire into flame.

Rise up and make no delay. Stretch out and gather a handful of an herb that will bring him back from whatever place he is in.

Where is the use of herbs, and his teeth clenched the way he could not use them?[196]

Take fire so in the devil’s name, and put it to the soles of his feet.

Let him alone, I say! [Dashes away the sod.

I will not leave him alone! I will not give in to leave him swooning there and the country waiting for him to awake!

I tell you I awoke him! I sent him into thieves’ company! I will not have him wakened again and evil things it maybe waiting to take hold of him! Back from him, back, I say! Will you dare to lay a hand on me! You cannot do it! You cannot touch him against my will!

Mind yourself, do not be bringing us under the curse of the Church.

It is God has him in His care. It is He is awaking him. [MARTIN has risen to his elbow.] Do not touch him, do not speak to him, he may be hearing great secrets.[197]

That music, I must go nearer—sweet marvellous music—louder than the trampling of the unicorns; far louder, though the mountain is shaking with their feet—high joyous music.

Hush, he is listening to the music of Heaven!

Take me to you, musicians, wherever you are! I will go nearer to you; I hear you better now, more and more joyful; that is strange, it is strange.

He is getting some secret.

It is the music of Paradise, that is certain, somebody said that. It is certainly the music of Paradise. Ah, now I hear, now I understand. It is made of the continual clashing of swords!

That is the best music. We will clash them sure enough. We will clash our swords and our pikes on the bayonets of the red soldiers. It is well you rose up from the dead to lead us! Come on, now, come on![198]

Who are you? Ah, I remember—where are you asking me to come to?

To come on, to be sure, to the attack on the barracks at Aughanish. To carry on the work you took in hand last night.

What work did I take in hand last night? Oh, yes, I remember—some big house—we burned it down—but I had not understood the vision when I did that. I had not heard the command right. That was not the work I was sent to do.

Rise up now and bid us what to do. Your great name itself will clear the road before you. It is you yourself will have freed all Ireland before the stooks will be in stacks!

Listen, I will explain—I have misled you. It is only now I have the whole vision plain. As I lay there I saw through everything, I know all. It was but a frenzy that going out to burn and to destroy. What have I to do with the foreign army? What I have to pierce is the[199] wild heart of time. My business is not reformation but revelation.

If you are going to turn back now from leading us, you are no better than any other traitor that ever gave up the work he took in hand. Let you come and face now the two hundred men you brought out daring the power of the law last night, and give them your reason for failing them.

I was mistaken when I set out to destroy Church and Law. The battle we have to fight is fought out in our own mind. There is a fiery moment, perhaps once in a lifetime, and in that moment we see the only thing that matters. It is in that moment the great battles are lost and won, for in that moment we are a part of the host of heaven.

Have you betrayed us to the naked hangman with your promises and with your drink? If you brought us out here to fail us and to ridicule us, it is the last day you will live!

The curse of my heart on you! It would be right to send you to your own place on the flagstone[200] of the traitors in hell. When once I have made an end of you I will be as well satisfied to be going to my death for it as if I was going home!

Father John, Father John, can you not hear? Can you not see? Are you blind? Are you deaf?

What is it? What is it?

There on the mountain, a thousand white unicorns trampling; a thousand riders with their swords drawn—the swords clashing! Oh, the sound of the swords, the sound of the clashing of the swords!

Stop—do you not see he is beyond the world?

Keep your hand off him, Johnny Bacach. If he is gone wild and cracked, that’s natural. Those that have been wakened from a trance on a sudden are apt to go bad and light in the head.[201]

If it is madness is on him, it is not he himself should pay the penalty.

To prey on the mind it does, and rises into the head. There are some would go over any height and would have great power in their madness. It is maybe to some secret cleft he is going, to get knowledge of the great cure for all things, or of the Plough that was hidden in the old times, the Golden Plough.

It seemed as if he was talking through honey. He had the look of one that had seen great wonders. It is maybe among the old heroes of Ireland he went raising armies for our help.

God take him in his care and keep him from lying spirits and from all delusions!

We have got candles here, Father. We had them to put around his body. Maybe they would keep away the evil things of the air.

Light them so, and he will say out a Mass for him the same as in a lime-washed church.

Where is he? I am come to warn him. The destruction he did in the night-time has been heard of. The soldiers are out after him and the constables—there are two of the constables not far off—there are others on every side—they heard he was here in the mountain—where is he?

He has gone up the path.

Hurry after him! Tell him to hide himself—this attack he had a hand in is a hanging crime. Tell him to hide himself, to come to me when all is quiet—bad as his doings are, he is my own brother’s son; I will get him on to a ship that will be going to France.

That will be best, send him back to the Brothers and to the wise Bishops. They can unravel this tangle, I cannot. I cannot be sure of the truth.

Here are the constables, he will see them and get away. Say no word. The Lord be praised that he is out of sight.[203]

The man we are looking for, where is he? He was seen coming here along with you. You have to give him up into the power of the law.

We will not give him up. Go back out of this or you will be sorry.

We are not in dread of you or the like of you.

Throw them down over the rocks!

Give them to the picking of the crows!

Down with the law!

Hush! He is coming back. [To Constables.] Stop, stop—leave him to himself. He is not trying to escape, he is coming towards you.

There is a sort of a brightness about him. I misjudged him calling him a traitor. It is not to this world he belongs at all. He is over on the other side.[204]

I must know what he has to say. It is not from himself he is speaking.

Father John, Heaven is not what we have believed it to be. It is not quiet, it is not singing and making music, and all strife at an end. I have seen it, I have been there. The lover still loves but with a greater passion, and the rider still rides but the horse goes like the wind and leaps the ridges, and the battle goes on always, always. That is the joy of Heaven, continual battle. I thought the battle was here, and that the joy was to be found here on earth, that all one had to do was to bring again the old wild earth of the stories—but no, it is not here; we shall not come to that joy, that battle, till we have put out the senses, everything that can be seen and handled, as I put out this candle. [He puts out candle.] We must put out the whole world as I put out this candle [puts out another candle]. We must put out the light of the stars and the light of the sun and the light of the[205] moon [puts out the rest of the candles], till we have brought everything to nothing once again. I saw in a broken vision, but now all is clear to me. Where there is nothing, where there is nothing—there is God!

Now we will take him!

We will never give him up to the law!

Make your escape! We will not let you be followed.

We have done for them, they will not meddle with you again.

Oh, he is down!

He is shot through the breast. Oh, who has dared meddle with a soul that was in the tumults on the threshold of sanctity?[206]

It was that gun went off and I striking it from the constable’s hand.

Ah, that is blood! I fell among the rocks. It is a hard climb. It is a long climb to the vineyards of Eden. Help me up. I must go on. The Mountain of Abiegnos is very high—but the vineyards—the vineyards!

It was you misled him with your foretelling that he was coming within the best day of his life.

Madness on him or no madness, I will not leave that body to the law to be buried with a dog’s burial or brought away and maybe hanged upon a tree. Lift him on the sacks, bring him away to the quarry; it is there on the hillside the boys will give him a great burying, coming on horses and bearing white rods in their hands.

He is gone and we can never know where that vision came from. I cannot know—the wise Bishops would have known.

To be shaping a lad through his lifetime, and he to go his own way at the last, and a queer way. It is very queer the world itself is, whatever shape was put upon it at the first.

To be too headstrong and too open, that is the beginning of trouble. To keep to yourself the thing that you know, and to do in quiet the thing you want to do. There would be no disturbance at all in the world, all people to bear that in mind!

Preface to the Fourth Edition.

The present version of The Countess Cathleen is not quite the version adopted by the Irish Literary Theatre a couple of years ago, for our stage and scenery were capable of little; and it may differ still more from any stage version I make in future, for it seems that my people of the waters and my unhappy dead, in the third act, cannot keep their supernatural essence, but must put on too much of our mortality, in any ordinary theatre. I am told that I must abandon a meaning or two and make my merchants carry away the treasure themselves. The act was written long ago, when I had seen so few plays that I took pleasure in stage effects. Indeed, I am not yet certain that a wealthy theatre could not shape it to an impressive pageantry, or that a theatre without any wealth could not lift it out of pageantry into the mind, with a dim curtain, and some dimly robed actors, and the beautiful voices that should be as important in poetical as in musical drama. The Elizabethan stage was so little imprisoned in material circumstance that the Elizabethan imagination was not strained by god or spirit, nor even by Echo herself—no, not even when she answered, as in The Duchess of Malfi, in clear, loud words which were not the words that had been spoken to her. We have made a prison-house of paint and canvas, where we have as little freedom as under our own roofs, for there is no freedom in a house that has been made with hands. All art moves in the cave of the Chimæra, or in the garden of the Hesperides, or in the more silent house of the gods, and neither cave, nor garden, nor house can show itself clearly but to the mind’s eye.[212]

Besides re-writing a lyric or two, I have much enlarged the note on The Countess Cathleen, as there has been some discussion in Ireland about the origin of the story, but the other notes[A] are as they have always been. They are short enough, but I do not think that anybody who knows modern poetry will find obscurities in this book. In any case, I must leave my myths and symbols to explain themselves as the years go by and one poem lights up another, and the stories that friends, and one friend in particular, have gathered for me, or that I have gathered myself in many cottages, find their way into the light. I would, if I could, add to that great and complicated inheritance of images which written literature has substituted for the greater and more complex inheritance of spoken tradition, to that majestic heraldry of the poets some new heraldic images gathered from the lips of the common people. Christianity and the old nature faith have lain down side by side in the cottages, and I would proclaim that peace as loudly as I can among the kingdoms of poetry, where there is no peace that is not joyous, no battle that does not give life instead of death; I may even try to persuade others, in more sober prose, that there can be no language more worthy of poetry and of the meditation of the soul than that which has been made, or can be made, out of a subtlety of desire, an emotion of sacrifice, a delight in order, that are perhaps Christian, and myths and images that mirror the energies of woods and streams, and of their wild creatures. Has any part of that majestic heraldry of the poets had a very different fountain? Is it not the ritual of the marriage of heaven and earth?

These details may seem to many unnecessary; but after all one writes poetry for a few careful readers and for a few friends, who will not consider such details very unnecessary. When Cimabue had the cry it was, it seems, worth thinking[213] of those that run; but to-day, when they can write as well as read, one can sit with one’s companions under the hedgerow contentedly. If one writes well and has the patience, somebody will come from among the runners and read what one has written quickly, and go away quickly, and write out as much as he can remember in the language of the highway.

January, 1901.

[A] I have left them out of this edition as Lady Gregory’s Cuchulain of Muirthemne and Gods and Fighting Men have made them unnecessary. When I began to write, the names of the Irish heroes were almost unknown even in Ireland.

The Countess Cathleen.—I found the story of the Countess Cathleen in what professed to be a collection of Irish folklore in an Irish newspaper some years ago. I wrote to the compiler, asking about its source, but got no answer, but have since heard that it was translated from Les Matinées de Timothé Trimm a good many years ago, and has been drifting about the Irish press ever since. Léo Lespès gives it as an Irish story, and though the editor of Folklore has kindly advertised for information, the only Christian variant I know of is a Donegal tale, given by Mr. Larminie in his West Irish Folk Tales and Romances, of a woman who goes to hell for ten years to save her husband and stays there another ten, having been granted permission to carry away as many souls as could cling to her skirt. Léo Lespès may have added a few details, but I have no doubt of the essential antiquity of what seems to me the most impressive form of one of the supreme parables of the world. The parable came to the Greeks in the sacrifice of Alcestis, but her sacrifice was less overwhelming, less apparently irremediable. Léo Lespès tells the story as follows:—