The Project Gutenberg EBook of On Canada's Frontier, by Julian Ralph

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: On Canada's Frontier

Sketches of History, Sport, and Adventure and of the

Indians, Missionaries, Fur-traders, and Newer Settlers of

Western Canada

Author: Julian Ralph

Release Date: February 7, 2011 [EBook #35208]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ON CANADA'S FRONTIER ***

Produced by Marcia Brooks, Ross Cooling and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Canada Team at

http://www.pgdpcanada.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet

Archive/Canadian Libraries)

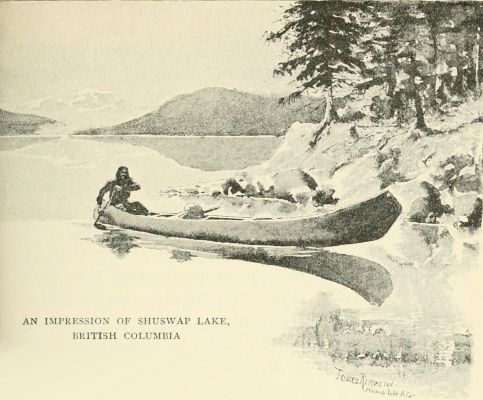

If all those into whose hands this book may fall were as well informed upon the Dominion of Canada as are the people of the United States, there would not be needed a word of explanation of the title of this volume. Yet to those who might otherwise infer that what is here related applies equally to all parts of Canada, it is necessary to explain that the work deals solely with scenes and phases of life in the newer, and mainly the western, parts of that country. The great English colony which stirs the pages of more than two centuries of history has for its capitals such proud and notable cities as Montreal, Quebec, Toronto, Halifax, and many others, to distinguish the progressive civilization of the region east of Lake Huron—the older provinces. But the Canada of the geographies of to-day is a land of greater area than the United States; it is, in fact, the "British America" of old. A great trans-Canadian railway has joined the ambitious province of the Pacific slope to the provinces of old Canada with stitches of steel across the Plains. There the same mixed surplusage of Europe that settled our own West is elbowing the fur-trader and the Indian out of the way, and is laying out farms far north, in the smiling Peace River district, where it was only a little while ago supposed that there were but two seasons, winter and late spring. It is with that new part of Canada, between the ancient and well-populated provinces and the sturdy new cities of the Pacific Coast, that this book deals. Some references to the North are added in those chapters that treat of hunting and fishing and fur-trading.

The chapters that compose this book originally formed a series of papers which recorded journeys and studies made in Canada during the past three years. The first one to be published was that which describes a settler's colony in which a few titled foreigners took the lead; the others were written so recently that they should possess the same interest and value as if they here first met the public eye. What that interest and value amount to is for the reader to judge, the author's position being such that he may only call attention to the fact that he had access to private papers and documents when he prepared the sketches of the Hudson Bay Company, and that, in pursuing information about the great province of British Columbia, he was not able to learn that a serious and extended study of its resources had ever been made. The principal studies and sketches were prepared for and published in Harper's Magazine. The spirit in which they were written was solely that of one who loves the open air and his fellow-men of every condition and color, and who has had the good-fortune to witness in newer Canada something of the old and almost departed life of the plainsmen and woodsmen, and of the newer forces of nation-building on our continent.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | Titled Pioneers | 1 |

| II. | Chartering a Nation | 11 |

| III. | A Famous Missionary | 53 |

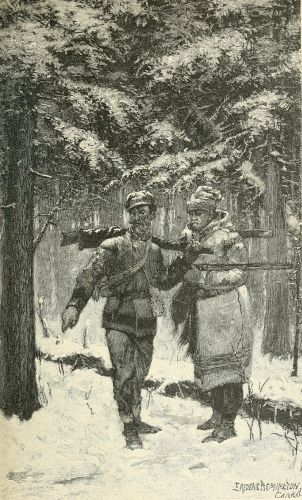

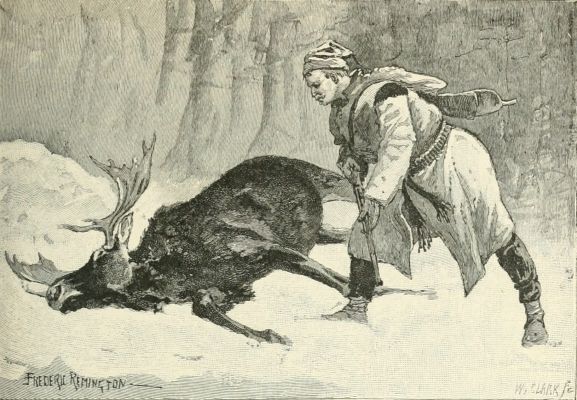

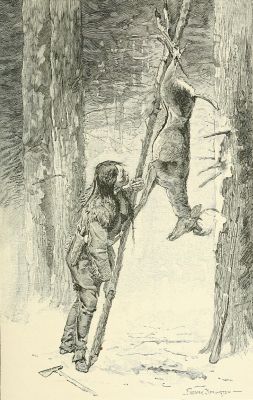

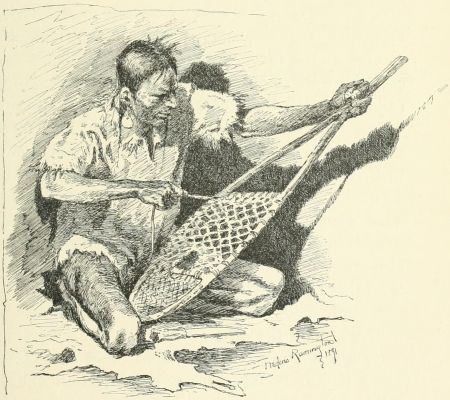

| IV. | Antoine's Moose-yard | 66 |

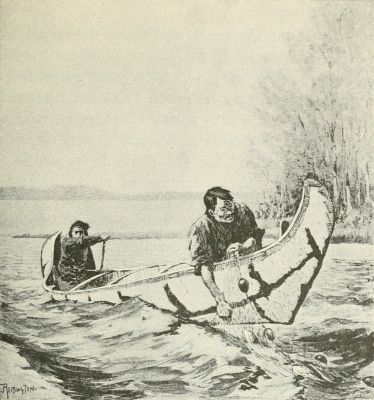

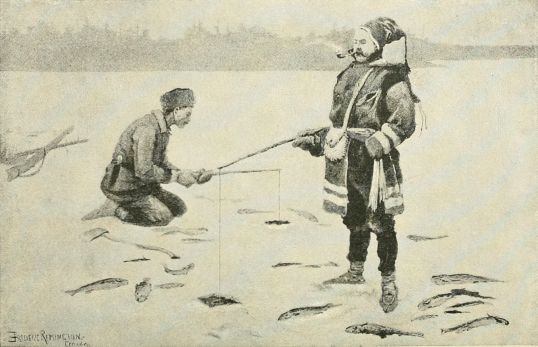

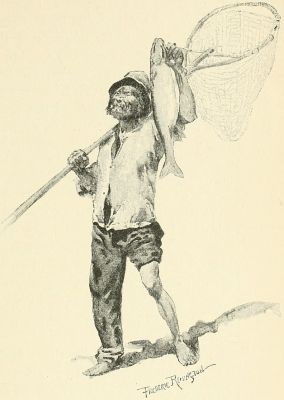

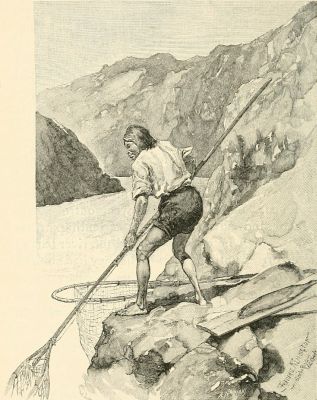

| V. | Big Fishing | 115 |

| VI. | "A Skin for a Skin" | 134 |

| VII. | "Talking Musquash" | 190 |

| VIII. | Canada's El Dorado | 214 |

| IX. | Dan Dunn's Outfit | 290 |

There is a very remarkable bit of this continent just north of our State of North Dakota, in what the Canadians call Assiniboia, one of the North-west Provinces. Here the plains reach away in an almost level, unbroken, brown ocean of grass. Here are some wonderful and some very peculiar phases of immigration and of human endeavor. Here is Major Bell's farm of nearly one hundred square miles, famous as the Bell Farm. Here Lady Cathcart, of England, has mercifully established a colony of crofters, rescued from poverty and oppression. Here Count Esterhazy has been experimenting with a large number of Hungarians, who form a colony which would do better if those foreigners were not all together, with only each other to imitate—and to commiserate. But, stranger than all these, here is a little band of distinguished Europeans, partly noble and partly scholarly, gathered together in as lonely a spot as can be found short of the Rockies or the far northern regions of this continent.

These gentlemen are Dr. Rudolph Meyer, of Berlin, the Comte de Cazes and the Comte de Raffignac, of France, and M. Le Bidau de St. Mars, of that country also. They form, in all probability, the most distinguished and aristocratic little band of immigrants and farmers in the New World.

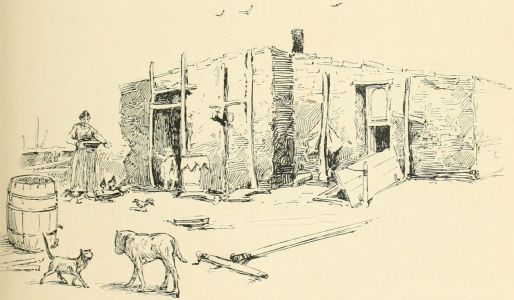

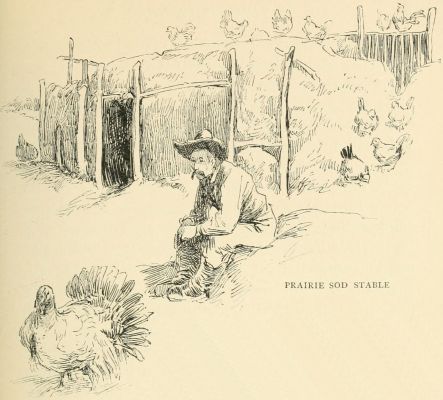

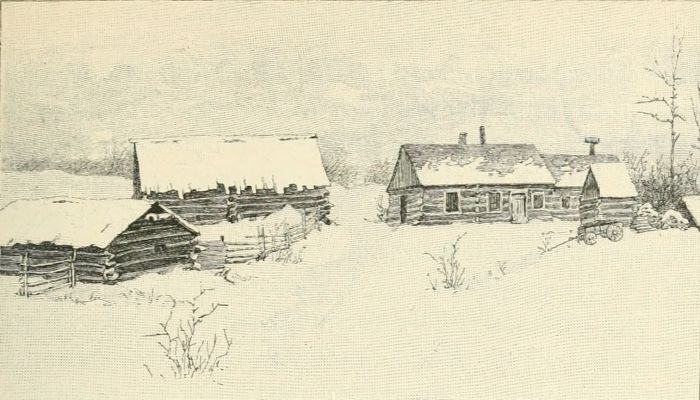

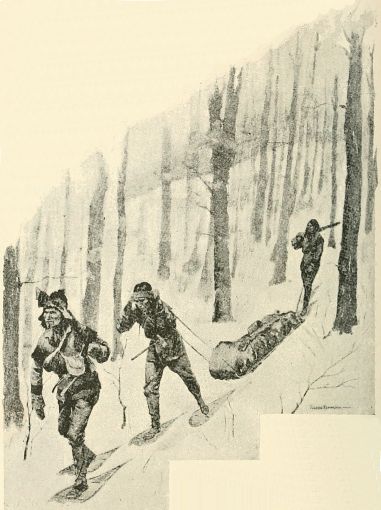

Seventeen hundred miles west of Montreal, in a vast prairie where settlers every year go mad from loneliness, these polished Europeans till the soil, strive for prizes at the provincial fairs, fish, hunt, read the current literature of two continents, and are happy. The soil in that region is of remarkable depth and richness, and is so black that the roads and cattle-trails look like ink lines on brown paper. It is part of a vast territory of uniform appearance, in one portion of which are the richest wheat-lands of the continent. The Canadian Pacific Railway crosses Assiniboia,[3] with stops about five miles apart—some mere stations and some small settlements. Here the best houses are little frame dwellings; but very many of the settlers live in shanties made of sods, with such thick walls and tight roofs, all of sod, that the awful winters, when the mercury falls to forty degrees below zero, are endured in them better than in the more costly frame dwellings.

I stopped off the cars at Whitewood, picking that four-year-old village out at hap-hazard as a likely point at which to see how the immigrants live in a brand-new country. I had no idea of the existence of any of the persons I found there. The most perfect hospitality is offered to strangers in such infant communities, and while enjoying the shelter of a merchant's house I obtained news of the distinguished settlers, all of whom live away from the railroad in solitude not to [4]be conceived by those who think their homes the most isolated in the older parts of the country. I had only time to visit Dr. Rudolph Meyer, five miles from Whitewood, in the valley of the Pipestone.

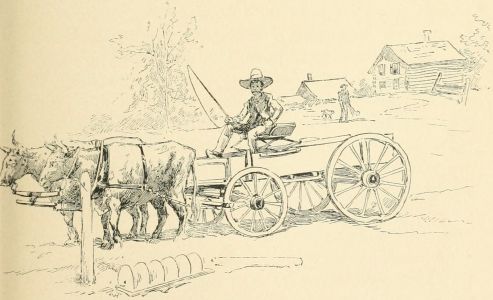

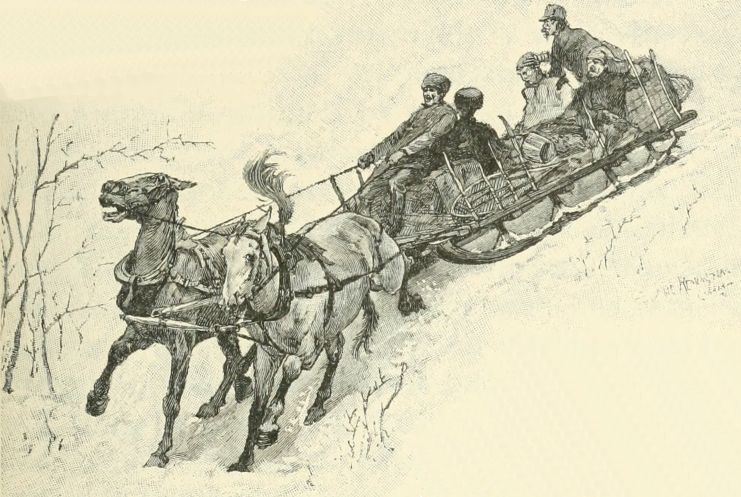

The way was across a level prairie, with here and there a bunch of young wolf-willows to break the monotonous scene, with tens of thousands of gophers sitting boldly on their haunches within reach of the wagon whip, with a sod house in sight in one direction at one time and a frame house in view at another. The talk of the driver was spiced with news of abundant wild-fowl, fewer deer, and marvellously numerous small quadrupeds, from wolves and foxes down. He talked of bachelors living here and there alone on that sea of grass, for all the world like men in small boats on the ocean; and I saw, contrariwise, a man and wife [5]who blessed Heaven for an unheard-of number of children, especially prized because each new-comer lessened the loneliness. I heard of the long and dreadful winters when the snowfall is so light that horses and mules may always paw down to grass, though cattle stand and starve and freeze to death. I heard, too, of the way the snow comes in flurried squalls, in which men are lost within pistol-shot of their homes. In time the wagon came to a sort of coulee or hollow, in which some mechanics imported from Pa[6]ris were putting up a fine cottage for the Comte de Raffignac. Ten paces farther, and I stood on the edge of the valley of the Pipestone, looking at a scene so poetic, pastoral, and beautiful that in the whole transcontinental journey there were few views to compare with it.

Reaching away far below the level of the prairie was a bowl-like valley, a mile long and half as wide, with a crystal stream lying like a ribbon of silver midway between its sloping walls. Another valley, longer yet, served as an extension to this. On the one side the high grassy walls were broken with frequent gullies, while on the other side was a park-like growth of forest trees. Meadows and fields lay between, and nestling against the eastern or grassy wall was the quaint, old-fashioned German house of the learned doctor. Its windows looked out on those beautiful little valleys, the property of the doctor—a little world far below the great prairie out of which sportive and patient Time had hollowed it. Externally the long, low, steep-roofed house was German, ancient, and picturesque in appearance. Its main floor was all enclosed in the sash and glass frame of a covered porch, and outside of the walls of glass were heavy curtains of straw, to keep out the sun in summer and the cold in winter. In-doors the house is as comfortable as any in the world. Its framework is filled with brick, and its trimmings are all of pine, oiled and varnished. In the heart of the house is a great Russian stove—a huge box of brick-work, which is filled full of wood to make a fire that is made fresh every day, and that heats the house for twenty-four ho[7]urs. A well-filled wine-cellar, a well-equipped library, where Harper's Weekly, and Uber Land und Mer, Punch, Puck, and Die Fliegende Blätter lie side by side, a kindly wife, and a stumbling baby, tell of a combination of domestic joys that no man is too rich to envy. The library is the doctor's workshop. He is now engaged in compiling a digest of the economic laws of nations. He is already well known as the author of a History of Socialism (in Germany, the United States, Scandinavia, Russia, France, Belgium, and elsewhere), and also for his History of Socialism in Germany. He writes in French and German, and his works are published in Germany.

Dr. Meyer is fifty-three years old. He is a political exile, having been forced from Prussia for connection with an unsuccessful opposition to Bismarck. It is because he is a scholar seeking rest from the turmoil of politics that one is able to comprehend his living in this overlooked corner of the world. Yet when that is understood, and one knows what an Arcadia his little valley is, and how complete are his comforts within-doors, the placidity with which he smokes his pipe, drinks his beer, and is waited upon by servants imported from Paris, becomes less a matter for wonder than for congratulation. He has shared part of one valley with the Comte de Raffignac, who thinks there is nothing to compare with it on earth. The count has had his house built near the abruptly-broken edge of the prairie, so that he may look down upon the calm and beautiful valley and enjoy it, as he could not had he built in the valley itself. He is a youth of very old French family, who loves hunting and horses. He was contemplating the raising of horses for a business when I was there. But the count mars the romance of his membership in this little band by going to Paris now and then, as a young man would be likely to.

Out-of-doors one saw what untold good it does to the present and future settlers to have such men among them. The hot-houses, glazed vegetable beds, the plots of cultivated ground, the nurseries of young trees—all show at what cost of money and patience the Herr Doctor is experimenting with every tree and flower and vegetable and cereal to discover what can be grown with profit in that region of rich soil and short summers, and what cannot. He is in communication with the see[9]dsmen, to say nothing of the savants, of Europe and this country, and whatever he plants is of the best. Near his quaint dwelling he has a house for his gardener, a smithy, a tool-house, a barn, and a cheese-factory, for he makes gruyere cheese in great quantities. He also raises horses and cattle.

The Comte de Cazes has a sheltered, favored claim a few miles to the northward, near the Qu' Appele River. He lives in great comfort, and is so successful a farmer that he carries off nearly all the prizes for the province, especially those given for prime vegetables. He has his wife and daughter and one of his sons with him, and an abundance of means, as, indeed, these distinguished settlers all appear to have.

These men have that faculty, developed in all educated and thinking souls, which enables them to banish loneliness and entertain themselves. Still, though Dr. Meyer laughs at the idea of danger, it must have been a little disquieting to live as he does during the Riel rebellion, especially as an Indian reservation is close by, and wandering red men are seen every day upon the prairie. Indeed, the Government thought fit to send men of the North-west Mounted Police to visit the doctor twice a week as lately as a year after the close of the half-breed uprising.

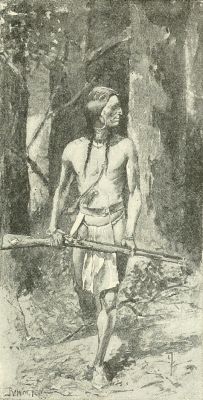

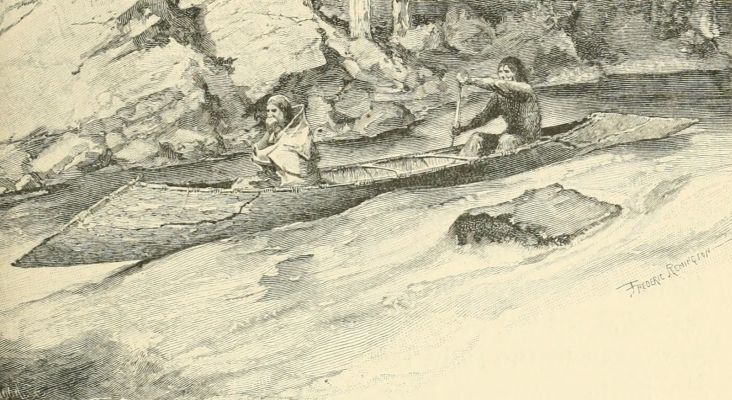

How it came about that we chartered the Blackfoot nation for two days had better not be told in straightforward fashion. There is more that is interesting in going around about the subject, just as in reality we did go around and about the neighborhood of the Indians before we determined to visit them.

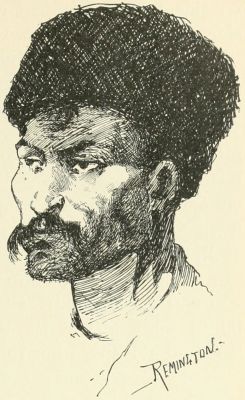

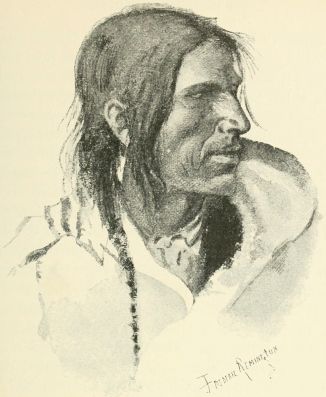

In the first place, the most interesting Indian I ever saw—among many kinds and many thousands—was the late Chief Crowfoot, of the Blackfoot people. More like a king than a chief he looked, as he strode upon the plains, in a magnificent robe of white bead-work as rich as ermine, with a gorgeous pattern illuminating its edges, a glorious sun worked into the front of it, and many artistic and chromatic figures sewed in gaudy beads upon its back. He wore an old white chimney-pot hat, bound around with eagle feathers, a splendid pair of chaperajos, all worked with beads at the bottoms and fringed along the sides, and bead-worked moccasins, for which any lover of the Indian or collector of his paraphernalia would have exchanged a new Winchester rifle without a second's hesitation. But though Crowfoot was so royally clothed, it was in himself that the kingly quality was most apparent. His face was extraordinarily like what portraits we have of Julius Cæsar, with the difference that Crowfoot had the complexion of an Egyptian m[12]ummy. The high forehead, the great aquiline nose, the thin lips, usually closed, the small, round, protruding chin, the strong jawbones, and the keen gray eyes composed a face in which every feature was finely moulded, and in which the warrior, the commander, and the counsellor were strongly suggested. And in each of these roles he played the highest part among the Indians of Canada from the moment that the whites and the red men contested the dominion of the plains until he died, a short time ago.

He was born and lived a wild Indian, and though the good fathers of the nearest Roman Catholic mission believe that he died a Christian, I am constrained to see in the reason for their thinking so only another proof of the consummate shrewdness of Crowfoot's life-long policy. The old king lay on his death-bed in his great wig-a-wam, with twenty-seven of his medicine-men around him, and never once did he pretend that he despised or doubted their magic. When it was evident that he was about to die, the conjurers ceased their long-continued, exhausting formula of howling, drumming, and all the rest, and, Indian-like, left Death to take his own. Then it was that one of the watchful, zealous priests, whose lives have indeed been like those of fathers to the wild Indians, slipped into the great tepee and administered the last sacrament to the old pagan.

"Do you believe?" the priest inquired.

"Yes, I believe," old Crowfoot grunted. Then he whispered, "But don't tell my people."

Among the last words of great men, those of Saponaxitaw (his Indian name) may never be recorded, but to the student of the American aborigine they betray more that is characteristic of the habitual attitude of mind of the wild red man towards civilizing influences than any words I ever knew one to utter.

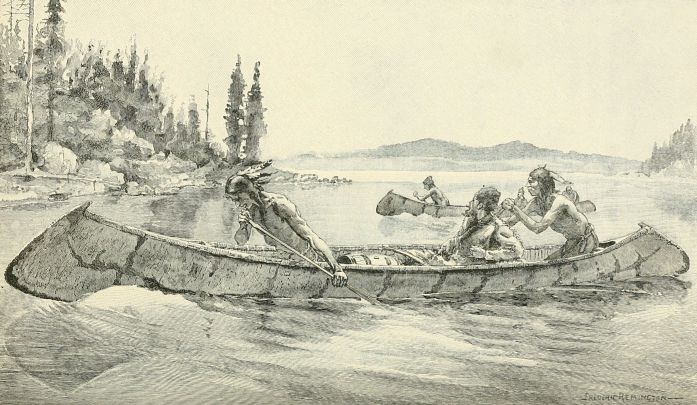

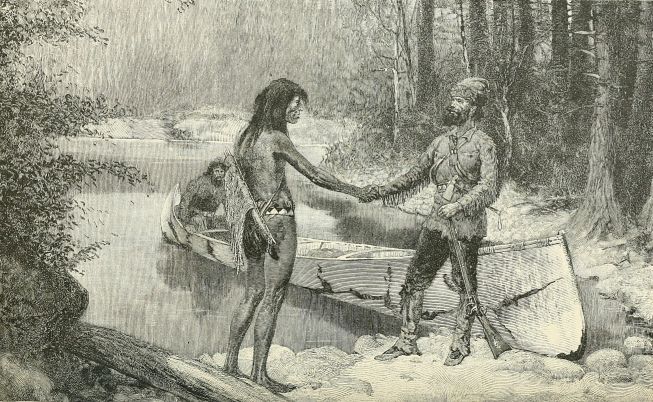

As the old chief crushed the bunch-grass beneath his gaudy moccasins at the time I saw him, and as his lesser chiefs and headmen strode behind him, we who looked on knew what a great part he was bearing and had taken in Canada. He had been chief of the most powerful and savage tribe in the North, and of several allied tribes as well, from the time when the region west of the Mississippi was terra incognita to all except a few fur traders and priests. His warriors ruled the Canadian wilderness, keeping the Ojibbeways and Crees in the forests to the east and north, routing the Crows, the Stonies, and the Big-Bellies whenever they pleased, and yielding to no tribe they met except the Sioux to the southward in our territory. The first white man Crowfoot ever knew intimately was Father Lacombe, the noble old missionary, whose fame is now world-wide among scholars. The peaceful priest and the warrior chief became fast friends, and from the day when the white men first broke down the border and swarmed upon the plains, until at the last they ran what Crowfoot called their "fire-wagons" (locomotives) through his land, he followed the priest's counselling in most important matters. He treated with the authorities, and thereafter hindered his braves from murder, massacre, and warfare. Better than that, during the Riel rebellion he more than any other man, or twenty men, kept t[14]he red man of the plains at peace when the French half-breeds, led by their mentally irresponsible disturber, rebelled against the Dominion authorities.

When Crowfoot talked, he made laws. While he spoke, his nation listened in silence. He had killed as many men as any Indian warrior alive; he was a mighty buffalo-slayer; he was torn, scarred, and mangled in skin, limb, and bone. He never would learn English or pretend to discard his religion. He was an Indian after the pattern of his ancestors. At eighty odd years of age there lived no red-skin who dared answer him back when he spoke his mind. But he was a shrewd man and an archdiplomatist. Because he had no quarrel with the whites, and because a grand old priest was his truest friend, he gave orders that his body should be buried in a coffin, Christian fashion, and as I rode over the plains in the summer of 1890 I saw his burial-place on top of a high hill, and knew that his bones were guarded night and day by watchers from among his people. Two or three days before he died his best horse was slaughtered for burial with him. He heard of it. "That was wrong," he said; "there was no sense in doing that; and besides, the horse was worth good money." But he was always at least as far as that in advance of his people, and it was natural that not only his horse, but his gun and blankets, his rich robes, and plenty of food to last him to the happy hunting-grounds, should have been buried with him.

There are different ways of judging which is the best Indian, but from the stand-point of him who would examine that distinct product of nature, the Indian as the white man found him, the Canadian Blackfeet are among if not quite the best. They are almost as primitive and natural as any, nearly the most prosperous, physically very fine, the most free from white men's vices. They are the most reasonable in their attitude towards the whites of any who hold to the true Indian philosophy. The sum of that philosophy is that civilization gets men a great many comforts, but bundles them up with so many rules and responsibilities and so much hard work that, after all, the wild Indian has the greatest amount of pleasure and the least share of care that men can hope for. That man is the fairest judge of the red-skins who considers them as children, governed mainly by emotion, and acting upon undisciplined impulse; and I know of no more hearty, natural children than the careless, improvident, impulsive boys and girls of from five to eighty years of age whom Crowfoot turned over to the care of Three Bulls, his brother.

The Blackfeet of Canada number about two thousand men, women, and children. They dwell upon a reserve of nearly five hundred square miles of plains land, watered by the beautiful Bow River, and almost within sight of the Rocky Mountains. It is in the province of Alberta, north of our Montana. There were three thousand and more of these Indians when the Canadian Pacific Railway was built across their hunting-ground, seven or eight years ago, but they are losing numbers at the rate of two hundred and fifty a year, roug[16]hly speaking. Their neighbors, the tribes called the Bloods and the Piegans, are of the same nation. The Sarcis, once a great tribe, became weakened by disease and war, and many years ago begged to be taken into the confederation. These tribes all have separate reserves near to one another, but all have heretofore acknowledged each Blackfoot chief as their supreme ruler. Their old men can remember when they used to roam as far south as Utah, and be gone twelve months on the war-path and on their foraging excursions for horses. They chased the Crees as far north as the Crees would run, and that was close to the arctic circle. They lived in their war-paint and by the chase. Now they are caged. They live unnaturally and die as unnaturally, precisely like other wild animals shut up in our parks. Within their park each gets a pound of meat with half a pound of flour every day. Not much comes to them besides, except now and then a little game, tobacco, and new blankets. They are so poorly lodged and so scantily fed that they are not fit to confront a Canadian winter, and lung troubles prey among them.

It is a harsh way to put it (but it is true of our own government also) to say that one who has looked the subject over is apt to decide that the policy of the Canadian Government has been to make treaties with the dangerous tribes, and to let the peaceful ones starve. The latter do not need to starve in Canada, fortunately; they trust to the Hudson Bay Company for food and care, and not in vain. Having treated with the wilder Indians, the rest of the policy is to send the brig[17]htest of their boys to trade-schools, and to try to induce the men to till the soil. Those who do so are then treated more generously than the others. I have my own ideas with which to meet those who find nothing admirable in any except a dead Indian, and with which to discuss the treatment and policy the live Indian endures, but this is not the place for the discussion. Suffice it that it is not to be denied that between one hundred and fifty and two hundred Blackfeet are learning to maintain several plots of farming land planted with oats and potatoes. This they are doing with success, and with the further result of setting a good example to the rest. But most of the bucks are either sullenly or stupidly clinging to the shadow and the memory of the life that is gone.

It was a recollection of that life which they portrayed for us. And they did so with a fervor, an abundance of detail and memento, and with a splendor few men have seen equalled in recent years—or ever may hope to witness again.

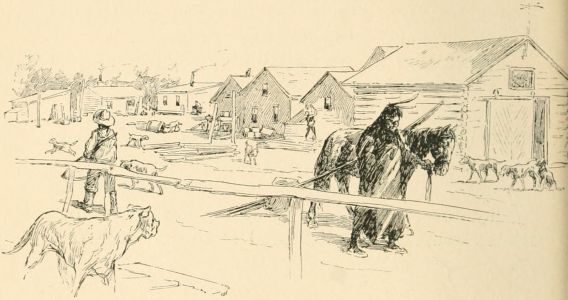

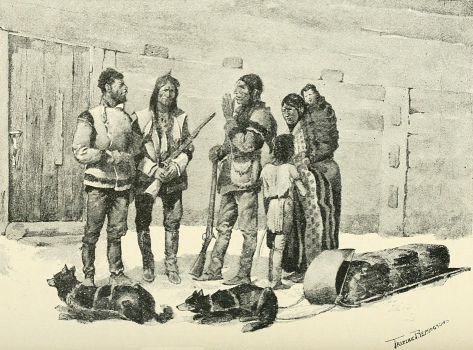

We left the cars at Gleichen, a little border town which depends almost wholly upon the Blackfeet and their visitors for its maintenance. It has two stores—one where the Indians get credit and high prices (and at which the red men deal), and one at which they may buy at low rates for cash, wherefore they seldom go there. It has two hotels and a half-dozen railway men's dwellings, and, finally, it boasts a tiny little station or barracks of the North-west Mounted Police, wherein the lower of the two rooms is fitted with a desk, and hung with pistols, guns, handcuffs, and cart[18]ridge belts, while the upper room contains the cots for the men at night.

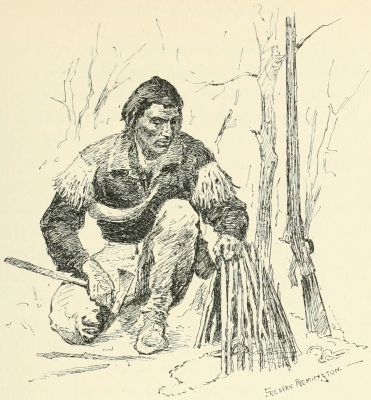

We went to the store that the Indians favor—just such a store as you see at any cross-roads you drive past in a summer's outing in the country—and there were half a dozen Indians beautifying the door-way and the interior, like magnified majolica-ware in a crockery-shop. They were standing or sitting about with thoughtful expressions, as Indians always do when they go shopping; for your true Indian generates such a contemplative mood when he is about to spend a quarter that one would fancy he must be the most prudent and deliberate of men, instead of what he really is—the greatest prodigal alive except the negro. These bucks might easily have been mistaken for waxworks. Unnaturally erect, with arms folded beneath their blankets, they stood or sat without moving a limb or muscle. Only when a new-comer entered did they stir. Then they turned their heads deliberately and looked at the visitor fixedly, as eagles look at you from out their cages. They were strapping fine fellows, each bundled up in a colored blanket, flapping cloth leg-gear, and yellow moccasins. Each had the front locks of his hair tied in an upright bunch, like a natural plume, and several wore little brass rings, like baby finger-rings, around certain side locks down beside their ears.

There they stood, motionless and speechless, waiting until the impulse should move them to buy what they wanted, with the same deliberation with which they had waited for the original impulse which sent them to the store. If Mr. Frenchman, who kept the store, had come from[19] behind his counter, English fashion, and had said: "Come, come; what d'you want? Speak up now, and be quick about it. No lounging here. Buy or get out." If he had said that, or anything like it, those Indians would have stalked out of his place, not to enter it again for a very long time, if ever. Bartering is a serious and complex performance to an Indian, and you might as well try to hurry an elephant up a gang-plank as try to quicken an Indian's procedure in trading.

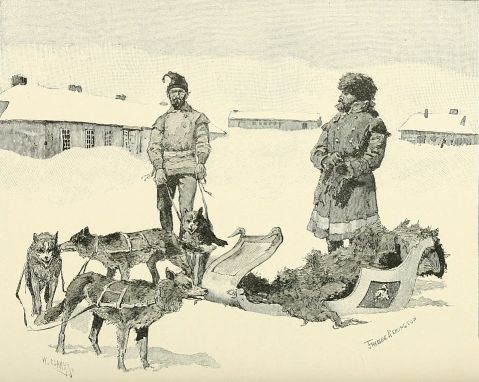

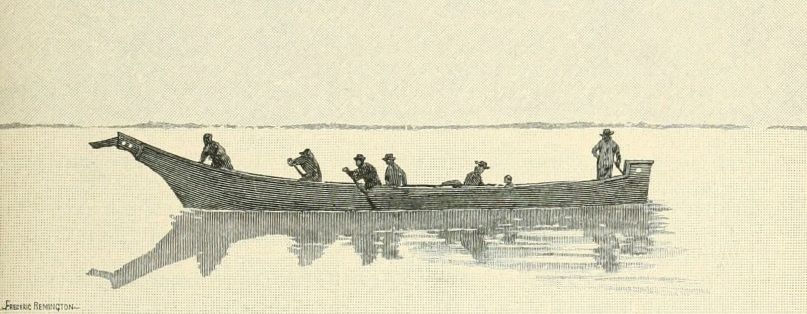

We purchased of the Frenchman a chest of tea, a great bag of lump sugar, and a small case of plug tobacco for gifts to the chief. Then we hired a buck-board wagon, and made ready for the journey to the reserve.

The road to the reserve lay several miles over the plains, and commanded a view of rolling grass land, like a brown sea whose waves were petrified, with here and there a group of sickly wind-blown trees to break the resemblance. The road was a mere wagon track and horse-trail through the grass, but it was criss-crossed with the once deep ruts that had been worn by countless herds of buffalo seeking water.

Presently, as we journeyed, a little line of sand-hills came into view. They formed the Blackfoot cemetery. We saw the "tepees of the dead" here and there on the knolls, some new and perfect, some old and weather-stained, some showing mere tatters of cotton flapping on the poles, and still others only skeleton tents, the poles remaining and the cotton covering gone completely. We knew what we would see if we looked into those "dead tepees" (being careful to approach fr[20]om the windward side). We would see, lying on the ground or raised upon a framework, a bundle that would be narrow at top and bottom, and broad in the middle—an Indian's body rolled up in a sheet of cotton, with his best bead-work and blanket and gun in the bundle, and near by a kettle and some dried meat and corn-meal against his feeling hungry on his long journey to the hereafter. As one or two of the tepees were new, we expected to see some family in mourning; and, sure enough, when we reached the great sheer-sided gutter which the Bow River has dug for its course through the plains, we halted our horse and looked down upon a lonely trio of tepees, with children playing around them and women squatted by the entrances. Three families had lost members, and were sequestered there in abject surrender to grief.

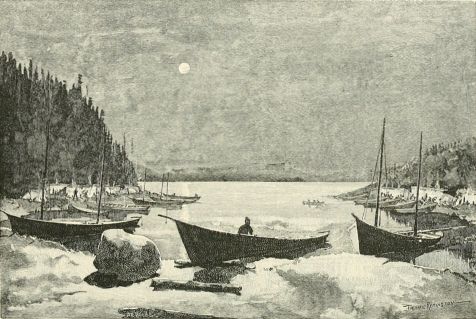

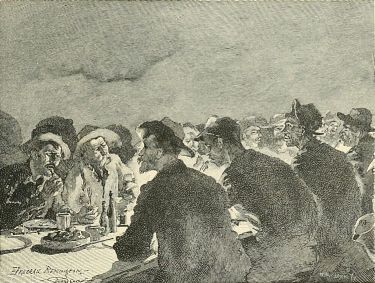

Those tents of the mourners were at our feet as we rode southward, down in the river gully, where the grass was green and the trees were leafy and thriving; but when we turned our faces to the eastward, where the river bent around a great promontory, what a sight met our gaze! There stood a city of tepees, hundreds of them, showing white and yellow and brown and red against the clear blue sky. A silent and lifeless city it seemed, for we were too far off to see the people or to hear their noises. The great huddle of little pyramids rose abruptly from the level bare grass against the flawless sky, not like one of those melancholy new treeless towns that white men are building all over the prairie, but rather like a mosquito fleet becalmed at sea. There are two camps on the Blackfo[21]ot Reserve, the North Camp and the South Camp, and this town of tents was between the two, and was composed of more households than both together; for this was the assembling for the sun-dance, their greatest religious festival, and hither had come Bloods, Piegans, and Sarcis as well as Blackfeet. Only the mourners kept away; for here were to be echoed the greatest ceremonials of that dead past, wherein lives dedicated to war and to the chase inspired the deeds of valor which each would now celebrate anew in speech or song. This was to be the anniversary of the festival at which the young men fastened themselves by a strip of flesh in their chests to a sort of Maypole rope, and tore their flesh apart to demonstrate their fitness to be considered braves. At this feast husbands had the right to confess their women, and to cut their noses off if they had been untrue, and if they yet preferred life to the death they richly merited. At this gala-time sacrifices of fingers were made by brave men to the sun. Then every warrior boasted of his prowess, and the young beaus feasted their eyes on gayly-clad maidens the while they calculated for what number of horses they could be purchased of their parents. And at each recurrence of this wonderful holiday-time every night was spent in feasting, gorging, and gambling. In short, it was the great event of the Indian year, and so it remains. Even now you may see the young braves undergo the torture; and if you may not see the faithless wives disciplined, you may at least perceive a score who have been, as well as hear the mighty boasting, and witness the dancing, gaming, and carous[22]ing.

We turned our backs towards the tented field, for we had not yet introduced ourselves to Mr. Magnus Begg, the Indian agent in charge of the reserve. We were soon within his official enclosure, where a pretty frame house, an office no bigger than a freight car, and a roomy barn and stable were all overtopped by a central flag-staff, and shaded by flourishing trees. Mr. Begg was at home, and, with his accomplished wife, welcomed us in such a hearty manner as one could hardly have expected, even where white folks were so "mighty unsartin" to appear as they are on the plains. The agent's house without is like any pretty village home in the East; and within, the only distinctive features are a number of ornamental mounted wild-beast's heads and a room whose walls are lined about with rare and beautiful Blackfoot curios in skin and stone and bead-work. But, to our joy, we found seated in that room the famous chief Old Sun. He is the husband of the most remarkable Indian squaw in America, and he would have been Crowfoot's successor were it not that he was eighty-seven years of age when the Blackfoot Cæsar died. As chief of the North Blackfeet, Old Sun boasts the largest personal following on the Canadian plains, having earned his popularity by his fighting record, his commanding manner, his eloquence, and by that generosity which leads him to give away his rations and his presents. No man north of Mexico can dress more gorgeously than he upon occasion, for he still owns a buckskin outfit beaded to the value of a Worth gown. Moreover, he owns a red coat, such as the Governmen[23]t used to give only to great chiefs. The old fellow had lost his vigor when we saw him, and as he sat wrapped in his blanket he looked like a half-emptied meal bag flung on a chair. He despises English, but in that marvellous Volapük of the plains called the sign language he told us that his teeth were gone, his hearing was bad, his eyes were weak, and his flesh was spare. He told his age also, and much else besides, and there is no one who reads this but could have readily understood his every statement and sentiment, conveyed solely by means of his hands and fingers. I noticed that he looked like an old woman, and it is a fact that old Indian men frequently look so. Yet no one ever saw a young brave whose face suggested a woman's, though their beardless countenances and long hair might easily create that appearance.

Mr. Remington was anxious to paint Old Sun and his squaw, particularly the latter, and he easily obtained permission, although when the time for the mysterious ordeal arrived next day the old chief was greatly troubled in his superstitious old brain lest some mischief would befall him through the medium of the painting. To the Indian mind the sun, which they worship, has magical, even devilish, powers, and Old Sun developed a fear that the orb of day might "work on his picture" and cause him to die. Fortunately I found in Mr. L'Hereux, the interpreter, a person who had undergone the process without dire consequences, was willing to undergo it again, and who added that his father and mother had submitted to the operation, and yet had lived to a yellow old age. When Old Sun [24]brought his wife to sit for her portrait I put all etiquette to shame in staring at her, as you will all the more readily believe when you know something of her history.

Old Sun's wife sits in the council of her nation—the only woman, white, red, or black, of whom I have ever heard who enjoys such a prerogative on this continent. She earned her peculiar privileges, if any one ever earned anything. Forty or more years ago she was a Piegan maiden known only in her tribe, and there for nothing more than her good origin, her comeliness, and her consequent value in horses. She met with outrageous fortune, but she turned it to such good account that she was speedily ennobled. She was at home in a little camp on the plains one day, and had wandered away from the tents, when she was kidnapped. It was in this wise: other camps were scattered near there. On the night before the day of her adventure a band of Crows stole a number of horses from a camp of the Gros Ventres, and very artfully trailed their plunder towards and close to the Piegan camp before they turned and made their way to their own lodges. When the Gros Ventres discovered their loss, and followed the trail that seemed to lead to the Piegan camp, the girl and her father, an aged chief, were at a distance from their tepees, unarmed and unsuspecting. Down swooped the Gros Ventres. They killed and scalped the old man, and then their chief swung the young girl upon his horse behind him, and binding her to him with thongs of buckskin, clashed off triumphantly for his own village. That has happened to many another Indian maide[25]n, most of whom have behaved as would a plaster image, saving a few days of weeping. Not such was Old Sun's wife. When she and her captor were in sight of the Gros Ventre village, she reached forward and stole the chief's scalping-knife out of its sheath at his side. With it, still wet with her father's blood, she cut him in the back through to the heart. Then she freed his body from hers, and tossed him from the horse's back. Leaping to the ground beside his body, she not only scalped him, but cut off his right arm and picked up his gun, and rode madly back to her people, chased most of the way, but bringing safely with her the three greatest trophies a warrior can wrest from a vanquished enemy. Two of them would have distinguished any brave, but this mere village maiden came with all three. From that day she has boasted the right to wear three eagle feathers.

Old Sun was a young man then, and when he heard of this feat he came and hitched the requisite number of horses to her mother's travois poles beside her tent. I do not recall how many steeds she was valued at, but I have heard of very high-priced Indian girls who had nothing except their feminine qualities to recommend them. In one case I knew that a young man, who had been casting what are called "sheep's eyes" at a maiden, went one day and tied four horses to her father's tent. Then he stood around and waited, but there was no sign from the tent. Next day he took four more, and so he went on until he had tied sixteen horses to the tepee. At the least they were worth $20, perhaps $30, apiece. At tha[26]t the maiden and her people came out, and received the young man so graciously that he knew he was "the young woman's choice," as we say in civilized circles, sometimes under very similar circumstances.

At all events, Old Sun was rich and powerful, and easily got the savage heroine for his wife. She was admitted to the Blackfoot council without a protest, and has since proven that her valor was not sporadic, for she has taken the war-path upon occasion, and other scalps have gone to her credit.

After a while we drove over to where the field lay littered with tepees. There seemed to be no order in the arrangement of the tents as we looked at the scene from a distance. Gradually the symptoms of a great stir and activity were observable, and we saw men and horses running about at one side of the nomad settlement, as well as hundreds of human figures moving in the camp. Then a nearer view brought out the fact that the tepees, which were of many sizes, were apt to be white at the base, reddish half-way up, and dark brown at the top. The smoke of the fires within, and the rain and sun without, paint all the cotton or canvas tepees like that, and very pretty is the effect. When closer still, we saw that each tepee was capped with a rude crown formed of pole ends—the ends of the ribs of each structure; that some of the tents were gayly ornamented with great geometric patterns in red, black, and yellow around the bottoms; and that others bore upon their sides rude but highly colored figures of animals—the clan sign of the family within. Against very many of [27]the frail dwellings leaned a travois, the triangle of poles which forms the wagon of the Indians. There were three or four very large tents, the headquarters of the chiefs of the soldier bands and of the head chief of the nation; and there was one spotless new tent, with a pretty border painted around its base, and the figure of an animal on either side. It was the new establishment of a bride and groom. A hubbub filled the air as we drew still nearer; not any noise occasioned by our approach, but the ordinary uproar of the camp—the barking of dogs, the shouts of frolicking children, the yells of young men racing on horseback and of others driving in their ponies. When we drove between the first two tents we saw that the camp had been systematically arranged in the form of a rude circle, with the tents in bunches around a great central space, as large as Madison Square if its corners were rounded off.

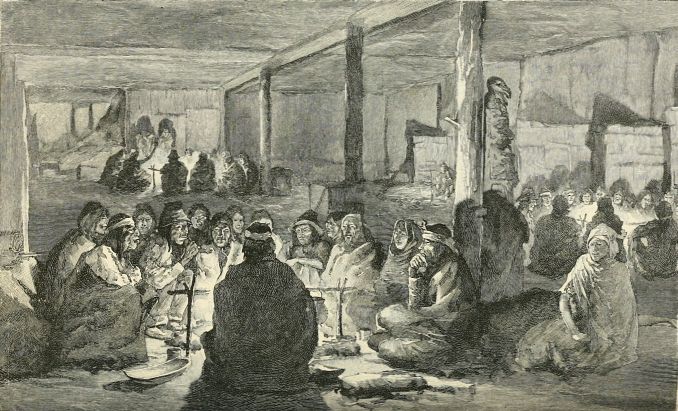

We were ushered into the presence of Three Bulls, in the biggest of all the tents. By common consent he was presiding as chief and successor to Crowfoot, pending the formal election, which was to take place at the feast of the sun-dance. European royalty could scarcely have managed to invest itself with more dignity or access to its presence with more formality than hedged about this blanketed king. He had assembled his chiefs and headmen to greet us, for we possessed the eminence of persons bearing gifts. He was in mourning for Crowfoot, who was his brother, and for a daughter besides, and the form of expression he gave to his grief caused him to wear nothing but a flanne[28]l shirt and a breech-cloth, in which he sat with his big brown legs bare and crossed beneath him. He is a powerful man, with an uncommonly large head, and his facial features, all generously moulded, indicate amiability, liberality, and considerable intelligence. Of middle age, smooth-skinned, and plump, there was little of the savage in his looks beyond what came of his long black hair. It was purposely wore unkempt and hanging in his eyes, and two locks of it were bound with many brass rings. When we came upon him our gifts had already been received and distributed, mainly to three or four relatives. But though the others sat about portionless, all were alike stolid and statuesque, and whatever feelings agitated their breasts, whether of satisfaction or disappointment, were equally hidden by all.

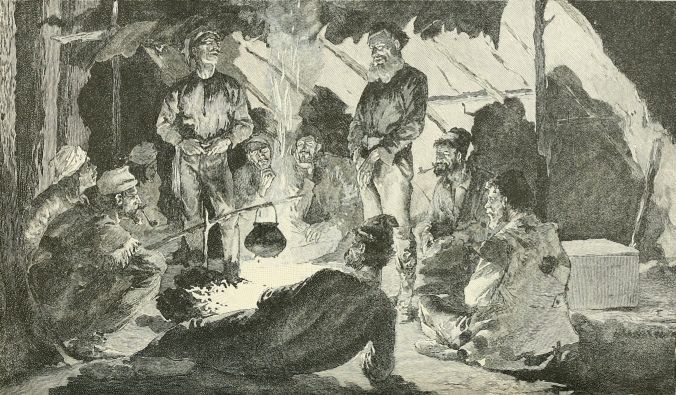

When we entered the big tepee we saw twenty-one men seated in a circle against the wall and facing the open centre, where the ground was blackened by the ashes of former fires. Three Bulls sat exactly opposite the queer door, a horseshoe-shaped hole reaching two feet above the ground, and extended by the partly loosened lacing that held the edges of the tent-covering together. Mr. L'Hereux, the interpreter, made a long speech in introducing each of us. We stood in the middle of the ring, and the chief punctuated the interpreter's remarks with that queer Indian grunt which it has ever been the custom to spell "ugh," but which you may imitate exactly if you will try to say "Ha" through your nose while your mouth is closed. As Mr. L'Hereux is a great talker, and is[29] of a poetic nature, there is no telling what wild fancy of his active brain he invented concerning us, but he made a friendly talk, and that was what we wanted. As each speech closed, Three Bulls lurched forward just enough to make the putting out of his hand a gracious act, yet not enough to disturb his dignity. After each salutation he pointed out a seat for the one with whom he had shaken hands. He announced to the council in their language that we were good men, whereat the council uttered a single "Ha" through its twenty-one noses. If you had seen the rigid stateliness of Three Bulls, and had felt the frigid self-possession of the twenty-one ramrod-mannered under-chiefs, as well as the deference which was in the tones of the other white men in our company, you would comprehend that we were made to feel at once honored and subordinate. Altogether we made an odd picture: a circle of men seated tailor fashion, and my own and Mr. Remington's black shoes marring the gaudy ring of yellow moccasins in front of the savages, as they sat in their colored blankets and fringed and befeathered gear, each with the calf of one leg crossed before the shin of the other.

But L'Hereux's next act after introducing us was one that seemed to indicate perfect indifference to the feelings of this august body. No one but he, who had spent a quarter of a century with them in closest intimacy, could have acted as he proceeded to do. He cast his eyes on the ground, and saw the mounds of sugar, tobacco, and tea heaped before only a certain few Indians. "Now who has done dose t'ing?" he inquired. "Oh, dat vill [30]nevaire do 'tall. You haf done dose t'ing, Mistaire Begg? No? Who den? Chief? Nevaire mind. I make him all rount again, vaire deeferent. You shall see somet'ing." With that, and yet without ceasing to talk for an instant, now in Indian and now in his English, he began to dump the tea back again into the chest, the sugar into the bag, and the plug tobacco in a heap by itself. Not an Indian moved a muscle—unless I was right in my suspicion that the corners of Three Bulls' mouth curved upward slightly, as if he were about to smile. "Vot kind of wa-a-y to do-o somet'ing is dat?" the interpreter continued, in his sing-song tone. "You moos' haf one maje-dome [major-domo] if you shall try satisfy dose Engine." He always called the Indians "dose Engine." "Dat chief gif all dose present to his broders und cousins, which are in his famille. Now you shall see me, vot I shall do." Taking his hat, he began filling it, now with sugar and now with tea, and emptying it before some six or seven chiefs. Finally, when a double share was left, he gave both bag and chest to Three Bulls, to whom he also gave all the tobacco. "Such tam-fool peezness," he went on, "I do not see in all my life. I make visitation to de t'ree soljier chief vhich shall make one grand darnce for dose gentlemen, und here is for dose soljier chief not anyt'ing 'tall, vhile everyt'ing was going to one lot of beggaire relation of T'ree Bull. Dat is what I call one tam-fool way to do some'ting."

The redistribution accomplished, Three Bulls wore a grin of satisfaction, and one chief who had lost a great [33]pile of presents, and who got nothing at all by the second division, stalked solemnly out of the tent, through not until Three Bulls had tossed the plugs of tobacco to all the men around the circle, precisely as he might have thrown bones to dogs, but always observing a certain order in making each round with the plugs. All were thus served according to their rank. Then Three Bulls rummaged with one hand behind him in the grass, and fetched forward a great pipe with a stone bowl and wooden handle—a sort of chopping-block of wood—and a large long-bladed knife. Taking a plug of tobacco in one hand and the knife in the other, he pared off enough tobacco to fill the pipe. Then he filled it, and passed it, stem foremost, to a young man on the left-hand side of the tepee. The superior chiefs all sat on the right-hand side. The young man knew that he had been chosen to perform the menial act of lighting the pipe, and he lighted it, pulling two or three whiffs of smoke to insure a good coal of fire in it before passing it back—though why it was not considered a more menial task to cut the tobacco and fill the pipe than to light it I don't know.

Three Bulls puffed the pipe for a moment, and then turning the stem from him, pointed it at the chief next in importance, and to that personage the symbol of peace was passed from hand to hand. When that chief had drawn a few whiffs, he sent the pipe back to Three Bulls, who then indicated to whom it should go next. Thus it went dodging about the circle like a marble on a bagatelle board. When it came to me, I hesitated a moment whether or not to smoke[34] it, but the desire to be polite outweighed any other prompting, and I sucked the pipe until some of the Indians cried out that I was "a good fellow."

While all smoked and many talked, I noticed that Three Bulls sat upon a soft seat formed of his blanket, at one end of which was one of those wickerwork contrivances, like a chair back, upon which Indians lean when seated upon the ground. I noticed also that one harsh criticism passed upon Three Bulls was just; that was that when he spoke, others might interrupt him. It was said that even women "talked back" to him at times when he was haranguing his people. Since no one spoke when Crowfoot talked, the comparison between him and his predecessor was injurious to him; but it was Crowfoot who named Three Bulls for the chieftainship. Besides, Three Bulls had the largest following (under that of the too aged Old Sun), and was the most generous chief and ablest politician of all. Then, again, the Government supported him with whatever its influence amounted to. This was because Three Bulls favored agricultural employment for the tribe, and was himself cultivating a patch of potatoes. He was in many other ways the man to lead in the new era, as Crowfoot had been for the era that was past.

When we retired from the presence of the chief, I asked Mr. L'Hereux how he had dared to take back the presents made to the Indians and then distribute them differently. The queer Frenchman said, in his indescribably confident, jaunty way:

"Why, dat is how you mus' do wid dose Engine. Nevaire ask one of dose Engine anyt'ing, but do dose t'ing which are right, and at de same time make explanashion what you are doing. Den dose Engine can say no t'ing 'tall. But if you first make explanashion and den try to do somet'ng, you will find one grand trouble. Can you explain dis and dat to one hive of de bees? Well, de hive of de bee is like dose Engine if you shall talk widout de promp' action."

He said, later on, "Dose Engine are children, and mus' not haf consideration like mans and women."

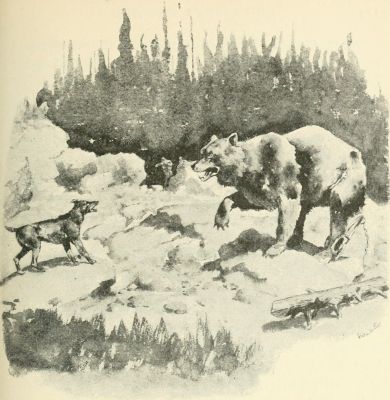

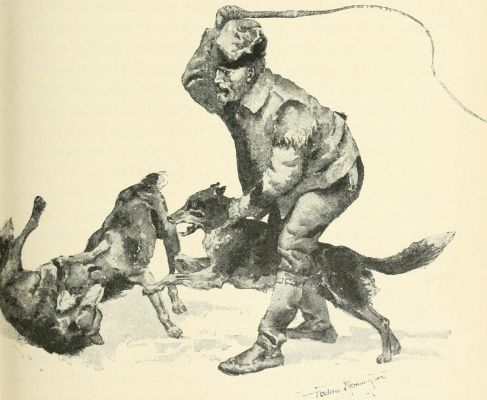

The news of our generosity ran from tent to tent, and the Black Soldier band sent out a herald to cry the news that a war-dance was to be held immediately. As immediately means to the Indian mind an indefinite and very enduring period, I amused myself by poking about the village, in tents and among groups of men or women, wherever chance led me. The herald rode from side to side of the enclosure, yelling like a New York fruit peddler. He was mounted on a bay pony, and was fantastically costumed with feathers and war-paint. Of course every man, woman, and child who had been in-doors, so to speak, now came out of the tepees, and a mighty bustle enlivened the scene. The worst thing about the camp was the abundance of snarling cur-dogs. It was not safe to walk about the camp without a cane or whip, on account of these dogs.

The Blackfeet are poor enough, in all conscience, from nearly every stand-point from which we judge civilized Communities, but their tribal possessions include several horses to each head of a family; and though the majority of the[36]ir ponies would fetch no more than $20 apiece out there, even this gives them more wealth per capita than many civilized peoples can boast. They have managed, also, to keep much of the savage paraphernalia of other days in the form of buckskin clothes, elaborate bead-work, eagle headdresses, good guns, and the outlandish adornments of their chiefs and medicine-men. Hundreds of miles from any except such small and distant towns as Calgary and Medicine Hat, and kept on the reserve as much as possible, there has come to them less damage by whiskey and white men's vices than perhaps most other tribes have suffered. Therefore it was still possible for me to see in some tents the squaws at work painting the clan signs on stretched skins, and making bead-work for moccasins, pouches, "chaps," and the rest. And in one tepee I found a young and rather pretty girl wearing a suit of buckskin, such as Cooper and all the past historians of the Indian knew as the co[37]nventional every-day attire of the red-skin. I say I saw the girl in a tent, but, as a matter of fact, she passed me out-of-doors, and with true feminine art managed to allow her blanket to fall open for just the instant it took to disclose the precious dress beneath it. I asked to be taken into the tent to which she went, and there, at the interpreter's request, she threw off her blanket, and stood, with a little display of honest coyness, dressed like the traditional and the theatrical belle of the wilderness. The soft yellowish leather, the heavy fringe upon the arms, seams, and edges of the garment, her beautiful beaded leggings and moccasins, formed so many parts of a very charming picture. For herself, her face was comely, but her figure was—an Indian's. The figure of the typical Indian woman shows few graceful curves.

The reader will inquire whether there was any real beauty, as we judge it, among these Indians. Yes, there was; at least there were good looks if there was not beauty. I saw perhaps a dozen fine-looking men, half a dozen attractive girls, and something like a hundred children of varying degrees of comeliness—pleasing, pretty, or beautiful. I had some jolly romps with the children, and so came to know that their faces and arms met my touch with the smoothness and softness of the flesh of our own little ones at home. I was surprised at this; indeed, the skin of the boys was of the texture of velvet. The madcap urchins, what riotous fun they were having! They flung arrows and darts, ran races and wrestled, and in some of their play they fairly swarmed all over one a[38]nother, until at times one lad would be buried in the thick of a writhing mass of legs and arms several feet in depth. Some of the boys wore only "G-strings" (as, for some reason, the breech-clout is commonly called on the prairie), but others were wrapped in old blankets, and the larger ones were already wearing the Blackfoot plume-lock, or tuft of hair tied and trained to stand erect above the forehead. The babies within the tepees were clad only in their complexions.

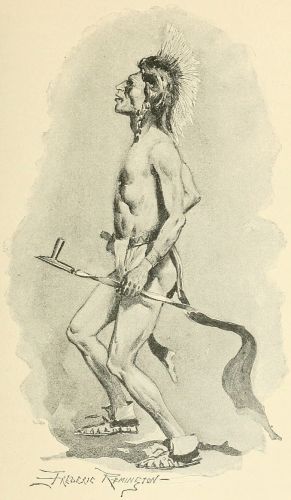

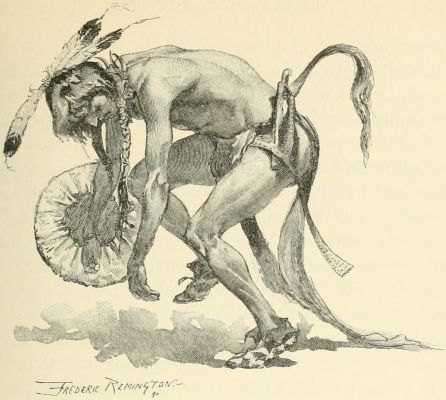

The result of an hour of waiting on our part and of yelling on the part of the herald resulted in a war-dance not very different in itself from the dances we have most of us seen at Wild West shows. An immense tomtom as big as the largest-sized bass-drum was set up between four poles, around which colored cloths were wrapped, and from the tops of which the same gay stuff floated on the wind in bunches of party-colored ribbons. Around this squatted four young braves, who pounded the drum-head and chanted a tune, which rose and fell between the shrillest and the deepest notes, but which consisted of simple monosyllabic sounds repeated thousands of times. The interpreter said that originally the Indians had words to their songs, but these were forgotten no man knows when, and only the so-called tunes (and the tradition that there once were words for them) are perpetuated. At all events, the four braves beat the drum and chanted, until presently a young warrior, hideous with war-paint, and carrying a shield and a tomahawk, came out of a tepee and began the dancing. It was the stiff-legged hopping, first on one foot and t[41][40][39]hen on the other, which all savages appear to deem the highest form the terpsichorean art can take. In the course of a few circles around the tomtom he began shouting of valorous deeds he never had performed, for he was too young to have ridden after buffalo or into battle. Presently he pretended to see upon the ground something at once fascinating and awesome. It was the trail of the enemy. Then he danced furiously and more limberly, tossing his head back, shaking his hatchet and many-tailed shield high aloft, and yelling that he was following the foe, and would not rest while a skull and a scalp-lock remained in conjunction among them. He was joined by three others, and all danced and yelled like madmen. At the last the leader came to a sort of standard made of a stick and some cloth, tore it out from where it had been thrust in the ground, and holding it far above his head, pranced once around the circle, and thus ended the dance.

The novelty and interest in the celebration rested in the surroundings—the great circle of tepees; the braves in their blankets stalking hither and thither; the dogs, the horses, the intrepid riders, dashing across the view. More strange still was the solemn line of the medicine-men, who, for some reason not explained to me, sat in a row with their backs to the dancers a city block away, and crooned a low guttural accompaniment to the tomtom. But still more interesting were the boys, of all grades of childhood, who looked on, while not a woman remained in sight. The larger boys stood about in groups, watching the spectacle with eyes afire with admiration, but the little fellows had[42] flung themselves on their stomachs in a row, and were supporting their chubby faces upon their little brown hands, while their elbows rested on the grass, forming a sort of orchestra row of Lilliputian spectators.

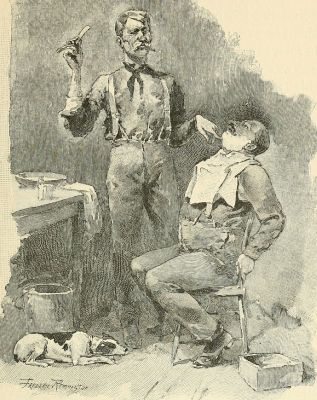

We arranged for a great spectacle to be gotten up on the next afternoon, and were promised that it should be as notable for the numbers participating in it and for the trappings to be displayed as any the Blackfeet had ever given upon their reserve. The Indians spent the entire night in carousing over the gift of tea, and we knew that if they were true to most precedents they would brew and drink every drop of it. Possibly some took it with an admixture of tobacco and wild currant to make them drunk, or, in reality, very sick—which is much the same thing to a reservation Indian. The compounds which the average Indian will swallow in the hope of imitating the effects of whiskey are such as to tax the credulity of those who hear of them. A certain patent "painkiller" ranks almost as high as whiskey in their estimation; but Worcestershire sauce and gunpowder, or tea, tobacco, and wild currant, are not at all to be despised when alcohol, or the money to get it with, is wanting. I heard a characteristic story about these red men while I was visiting them. All who are familiar with them know that if medicine is given them to take in small portions at certain intervals they are morally sure to swallow it all at once, and that the sicker it makes them, the more they will value it. On the Blackfoot Reserve, only a short time ago, our gentle and insinuating Sedlitz-powders were classed as childre[43]n's stuff, but now they have leaped to the front rank as powerful medicines. This is because some white man showed the Indian how to take the soda and magnesia first, and then swallow the tartaric acid. They do this, and when the explosion follows, and the gases burst from their mouths and noses, they pull themselves together and remark, "Ugh! him heap good."

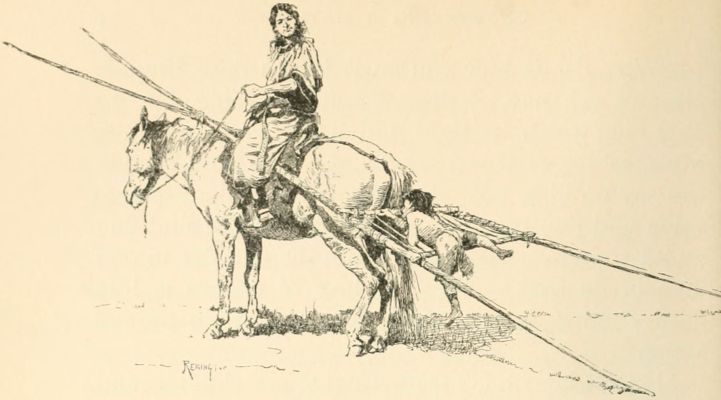

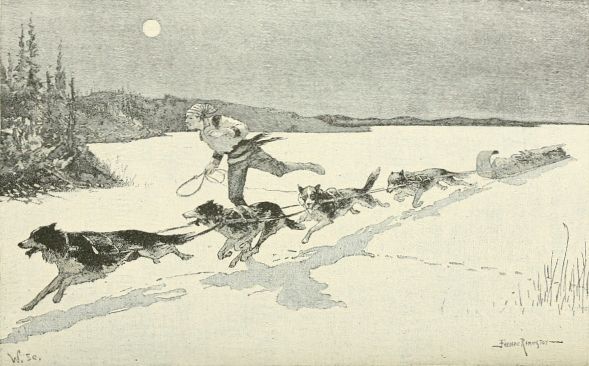

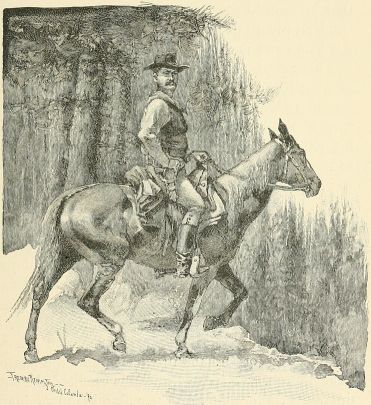

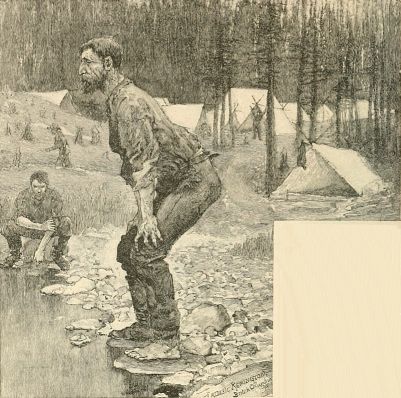

On the morning of the day of the great spectacle I rode with Mr. Begg over to the ration-house to see the meat distributed. The dust rose in clouds above all the trails as the cavalcade of men, women, children, travoises and dogs, approached the station. Men were few in the disjointed lines; most of them sent their women or children. All rode astraddle, some on saddles and some[44] bareback. As all urged their horses in the Indian fashion, which is to whip them unceasingly, and prod them constantly with spurless heels, the bobbing movement of the riders' heads and the gymnastics of their legs produced a queer scene. Here and there a travois was trailed along by a horse or a dog, but the majority of the pensioners were content to carry their meat in bags or otherwise upon their horses. While the slaughtering went on, and after that, when the beef was being chopped up into junks, I sat in the meat-contractor's office, and saw the bucks, squaws, and children come, one after another, to beg. I could not help noticing that all were treated with marked and uniform kindness, and I learned that no one ever struck one of the Indians, or suffered himself to lose his temper with them. A few of the men asked for blankets, but the squaws and the children wanted soap. It was said that when they first made their acquaintance with this symbol of civilization they mistook it for an article of diet, but that now they use it properly and prize it. When it was announced that the meat was ready, the butchers threw open an aperture in the wall of the ration-house, and the Indians huddled before it as if they had flung themselves against the house in a mass. I have seen boys do the same thing at the opening of a ticket window for the sale of gallery seats in a theatre. There was no fighting or quarrelling, but every Indian pushed steadily and silently with all his or her might. When one got his share he tore himself away from the crowd as briers are pulled out of hairy cloth. They are a hungry and an economical people. They bring p[45]ails for the beef blood, and they carry home the hoofs for jelly. After a steer has been butchered and distributed, only his horns and his paunch remain.

The sun blazed down on the great camp that afternoon and glorified the place so that it looked like a miniature Switzerland of snowy peaks. But it was hot, and blankets were stretched from the tent tops, and the women sat under them to catch the air and escape the heat. The salaried native policeman of the reserve, wearing a white stove-pipe hat with feathers, and a ridiculous blue coat, and Heaven alone knows what other absurdities, rode around, boasting of deeds he never performed, while a white cur made him all the more ridiculous by chasing him and yelping at his horse's tail.

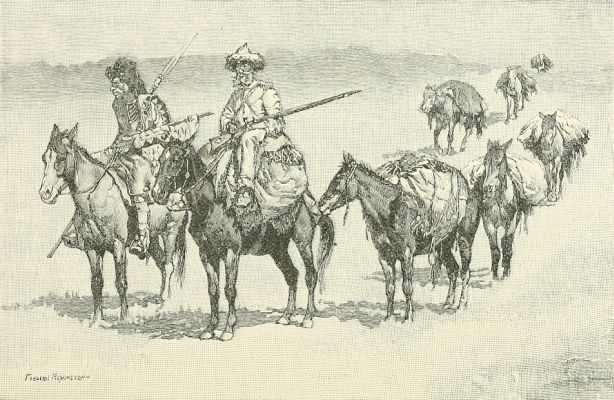

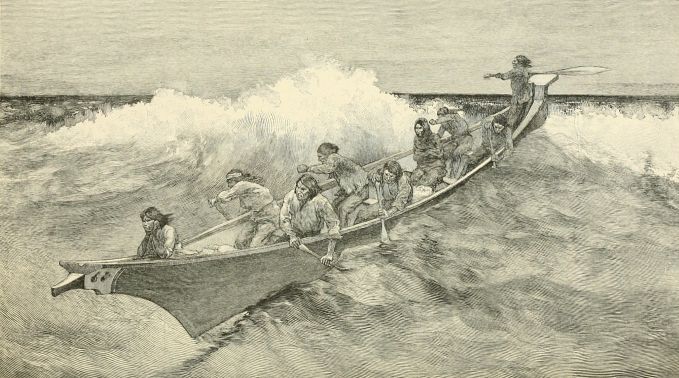

And then came the grand spectacle. The vast plain was forgotten, and the great campus within the circle of tents was transformed into a theatre. The scene was a setting of white and red tents that threw their clear-cut outlines against a matchless blue sky. The audience was composed of four white men and the Indian boys, who were flung about by the startled horses they were holding for us. The players were the gorgeous cavalrymen of nature, circling before their women and old men and children, themselves plumed like unheard-of tropical birds, the others displaying the minor splendor of the kaleidoscope. The play was "The Pony War-dance, or the Departure for Battle." The acting was fierce; not like the conduct of a mimic battle on our stage, but performed with the desperate zest of men who hope for distinction in war, and [46]may not trifle about it. It had the earnestness of a challenged man who tries the foils with a tutor. It was impressive, inspiring, at times wildly exciting.

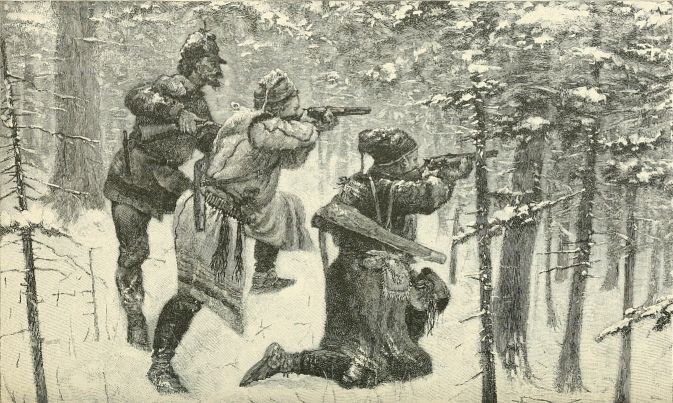

There were threescore young men in the brilliant cavalcade. They rode horses that were as wild as themselves. Their evolutions were rude, but magnificent. Now they dashed past us in single file, and next they came helter-skelter, like cattle stampeding. For a while they rode around and around, as on a race-course, but at times they deserted the enclosure, parted into small bands, and were hidden behind the curtains of their own dust, presently to reappear with a mad rush, yelling like maniacs, firing their pieces, and brandishing their arms and their finery wildly on high. The orchestra was composed of seven tomtoms that had been dried taut before a camp fire. The old men and the chiefs sat in a semicircle behind the drummers on the ground.

All the tribal heirlooms were in the display, the cherished gewgaws, trinkets, arms, apparel, and finery they had saved from the fate of which they will not admit they are themselves the victims. I never saw an old-time picture of a type of savage red man or of an extravagance of their costuming that was not revived in this spectacle. It was as if the plates in my old school-books and novels and tales of adventure were all animated and passing before me. The traditional Indian with the eagle plumes from crown to heels was there; so was he with the buffalo horns growing out of his skull; so were the idyllic braves in yellow buckskin fringed at every point. The shining bodies [49][48][47]of men, bare naked, and frescoed like a Bowery bar-room, were not lacking; neither were those who wore masses of splendid embroidery with colored beads. But there were as many peculiar costumes which I never had seen pictured. And not any two men or any two horses were alike. As barber poles are covered with paint, so were many of these choice steeds of the nation. Some were spotted all over with daubs of white, and some with every color obtainable. Some were branded fifty times with the white hand, the symbol of peace, but others bore the red hand and the white hand in alternate prints. There were horses painted with the figures of horses and of serpents and of foxes. To some saddles were affixed colored blankets or cloths that fell upon the ground or lashed the air, according as the horse cantered or raced. One horse was hung all round with great soft woolly tails of some white material. Sleigh-bells were upon several.

Only half a dozen men wore hats—mainly cowboy hats decked with feathers. Many carried rifles, which they used with one hand. Others brought out bows and arrows, lances decked with feathers or ribbons, poles hung with colored cloths, great shields brilliantly painted and fringed. Every visible inch of each warrior was painted, the naked ones being ringed, streaked, and striped from head to foot. I would have to catalogue the possessions of the whole nation to tell all that they wore between the brass rings in their hair and the cartridge-belts at their waists, and thus down to their beautiful moccasins.

Two strange features further distinguished their pageant. One was the appearance of two negro minstrels upon one horse. Both had blackened their faces and hands; both wore old stove-pipe hats and queer long-tailed white men's coats. One wore a huge false white mustache, and the other carried a coal-scuttle. The women and children roared with laughter at the sight. The two comedians got down from their horse, and began to make grimaces, and to pose this way and that, very comically. Such a performance had never been seen on the reserve before. No one there could explain where the men had seen negro minstrels. The other unexpected feature required time for development. At first we noticed that two little Indian boys kept getting in the way of the riders. As we were not able to find any fixed place of safety from the excited horsemen, we marvelled that these children were permitted to risk their necks.

Suddenly a hideously-painted naked man on horseback chased the little boys, leaving the cavalcade, and circling around the children. He rode back into the ranks, and still they loitered in the way. Then around swept the horsemen once more, and this time the naked rider flung himself from his horse, and seizing one boy and then the other, bore each to the ground, and made as if he would brain them with his hatchet and lift their scalps with his knife. The sight was one to paralyze an on-looker. But it was only a theatrical performance arranged for the occasion. The man was acting over again the proudest of his achievements. The boys played the parts of two white men whose scalps now grace his tepee and gladden h[51]is memory.

For ninety minutes we watched the glorious riding, the splendid horses, the brilliant trappings, and the paroxysmal fervor of the excited Indians. The earth trembled beneath the dashing of the riders; the air palpitated with the noise of their war-cries and bells. We could have stood the day out, but we knew the players were tired, and yet would not cease till we withdrew. Therefore we came away.[52]

We had enjoyed a never-to-be-forgotten privilege. It was if we had seen the ghosts of a dead people ride back to parody scenes in an era that had vanished. It was like the rising of the curtain, in response to an "encore," upon a drama that has been played. It was as if the sudden up-flashing of a smouldering fire lighted, once again and for an instant, the scene it had ceased to illumine.

The former chief of the Blackfeet—Crowfoot—and Father Lacombe, the Roman Catholic missionary to the tribe, were the most interesting and among the most influential public characters in the newer part of Canada. They had much to do with controlling the peace of a territory the size of a great empire.

The chief was more than eighty years old; the priest is a dozen years younger; and yet they represented in their experiences the two great epochs of life on this continent—the barbaric and the progressive. In the chief's boyhood the red man held undisputed sway from the Lakes to the Rockies. In the priest's youth he led, like a scout, beyond the advancing hosts from Europe. But Father Lacombe came bearing the olive branch of religion, and he and the barbarian became fast friends, intimates in a companionship as picturesque and out of the common as any the world could produce.

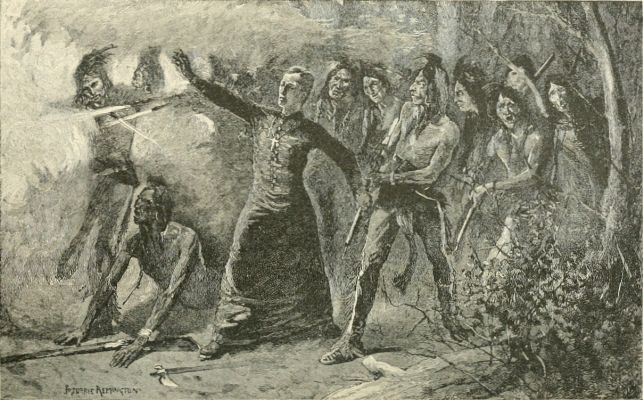

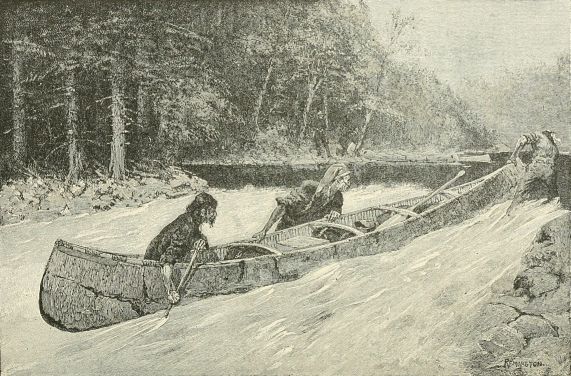

There is something very strange about the relations of the French and the French half-breeds with the wild men of the plains. It is not altogether necessary that the Frenchman should be a priest, for I have heard of French half-breeds in our Territories who showed again and again that they could make their way through bands of hostiles in perfect safety, though kno[54]wing nothing of the language of the tribes there in war-paint. It is most likely that their swarthy skins and black hair, and their knowledge of savage ways aided them. But when not even a French half-breed has dared to risk his life among angry Indians, the French missionaries went about their duty fearlessly and unscathed. There was one, just after the dreadful massacre of the Little Big Horn, who built a cross of rough wood, painted it white, fastened it to his buck-board, and drove through a country in which a white man with a pale face and blond hair would not have lived two hours.

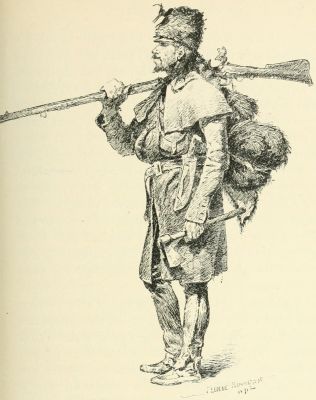

It must be remembered that in a vast region of country the French priest and voyageur and coureur des bois were the first white men the Indians saw, and while the explorers and traders seldom quarrelled with the red men or offered violence to them, the priests never did. They went about like women or children, or, rather, like nothing else than priests. They quickly learned the tongues of the savages, treated them fairly, showed the sublimest courage, and acted as counsellors, physicians, and friends. There is at least one brave Indian fighter in our army who will state it as his belief that if all the white men had done thus we would have had but little trouble with our Indians.

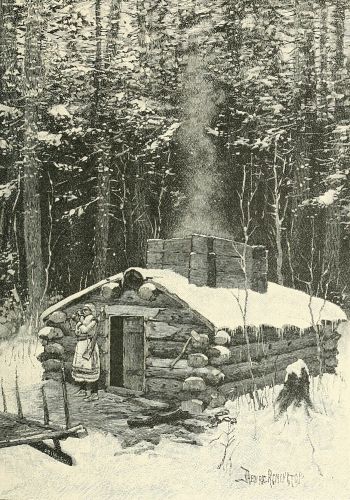

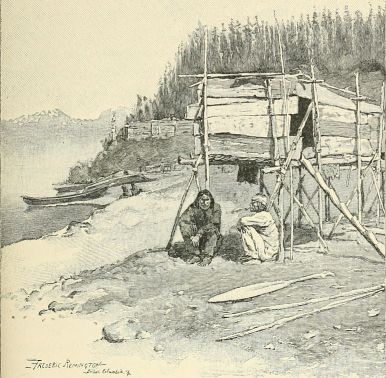

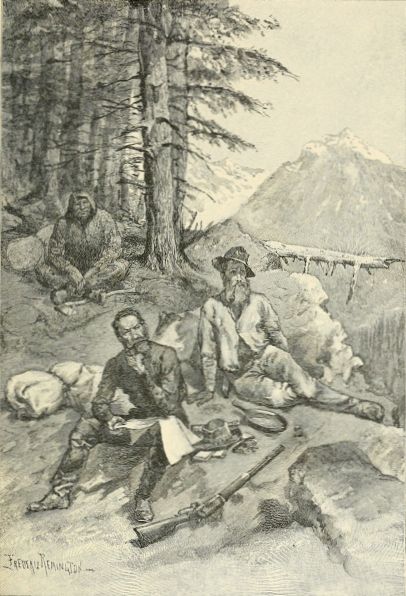

Father Lacombe was one of the priests who threaded the trails of the North-western timber land and the Far Western prairie when white men were very few indeed in that country, and the only settlements were those that had grown around the frontier forts and the still earlier mission chapels. For instance, in 1849, at twenty-[55]two years of age, he slept a night or two where St. Paul now weights the earth. It was then a village of twenty-five log-huts, and where the great building of the St. Paul Pioneer Press now stands, then stood the village chapel. For two years he worked at his calling on either side of the American frontier, and then was sent to what is now Edmonton, in that magical region of long summers and great agricultural capacity known as the Peace River District, hundreds of miles north of Dakota and Idaho. There the Rockies are broken and lowered, and the warm Pacific winds have rendered the region warmer than the land far to the south of it. But Father Lacombe went farther—400 miles north to Lake Labiche. There he found what he calls a fine colony of half-breeds. These were dependants of the Hudson Bay Company—white men from England, France, and the Orkney Islands, and Indians and half-breeds and their children. The visits of priests were so infrequent that in the intervals between them the white men and Indian women married one another, not without formality and the sanction of the colony, but without waiting for the ceremony of the Church. Father Lacombe was called upon to bless and solemnize many such matches, to baptize many children, and to teach and preach what scores knew but vaguely or not at all.

In time he was sent to Calgary in the province of Alberta. It is one of the most bustling towns in the Dominion, and the biggest place west of Winnipeg. Alberta is north of our Montana, and is all prairie-land; but from Father Lacombe's parsonage one sees the snow-capped Rockies, s[56]ixty miles away, lying above the horizon like a line of clouds tinged with the delicate hues of mother-of-pearl in the sunshine. Calgary was a mere post in the wilderness for years after the priest went there. The buffaloes roamed the prairie in fabulous numbers, the Indians used the bow and arrow in the chase, and the maps we studied at the time showed the whole region enclosed in a loop, and marked "Blackfoot Indians." But the other Indians were loath to accept this disposition of the territory as final, and the country thereabouts was an almost constant battle-ground between the Blackfoot nation of allied tribes and the Sioux, Crows, Flatheads, Crees, and others.

The good priest—for if ever there was a good man Father Lacombe is one—saw fighting enough, as he roamed with one tribe and the other, or journeyed from tribe to tribe. His mission led him to ignore tribal differences, and to preach to all the Indians of the plains. He knew the chiefs and headmen among them all, and so justly did he deal with them that he was not only able to minister to all without attracting the enmity of any, but he came to wield, as he does to-day, a formidable power over all of them.

He knew old Crowfoot in his prime, and as I saw them together they were like bosom friends. Together they had shared dreadful privation and survived frightful winters and storms. They had gone side by side through savage battles, and each respected and loved the other. I think I make no mistake in saying that all through his reign Crowfoot was the greatest Indian monarch in Canada; possibly no tribe in this country wa[57]s stronger in numbers during the last decade or two. I have never seen a nobler-looking Indian or a more king-like man. He was tall and straight, as slim as a girl, and he had the face of an eagle or of an ancient Roman. He never troubled himself to learn the English language; he had little use for his own. His grunt or his "No" ran all through his tribe. He never shared his honors with a squaw. He died an old bachelor, saying, wittily, that no woman would take him.

It must be remembered that the degradation of the Canadian Indian began a dozen or fifteen years later than that of our own red men. In both countries the railroads were indirectly the destructive agents, and Canada's great transcontinental line is a new institution. Until it belted the prairie the other day the Blackfoot Indians led very much the life of their fathers, hunting and trading for the whites, to be sure, but living like Indians, fighting like Indians, and dying like them. Now they don't fight, and they live and die like dogs. Amid the old conditions lived Crowfoot—a haughty, picturesque, grand old savage. He never rode or walked without his headmen in his retinue, and when he wished to exert his authority, his apparel was royal indeed. His coat of gaudy bead-work was a splendid garment, and weighed a dozen pounds. His leg-gear was just as fine; his moccasins would fetch fifty dollars in any city to-day. Doubtless he thought his hat was quite as impressive and king-like, but to a mere scion of effeminate civilization it looked remarkably like an extra tall plug hat, with no crown in the top and a lot of crows' plum[58]es in the band. You may be sure his successor wears that same hat to-day, for the Indians revere the "state hat" of a brave chief, and look at it through superstitious eyes, so that those queer hats (older tiles than ever see the light of St. Patrick's Day) descend from chief to chief, and are hallowed.

But Crowfoot died none too soon. The history of the conquest of the wilderness contains no more pathetic story than that of how the kind old priest, Father Lacombe, warned the chief and his lieutenants against the coming of the pale-faces. He went to the reservation and assembled the leaders before him in council. He told them that the white men were building a great railroad, and in a month their workmen would be in that virgin country. He told the wondering red men that among these laborers would be found many bad men seeking to sell whiskey, offering money for the ruin of the squaws. Reaching the greatest eloquence possible for him, because he loved the Indians and doubted their strength, he assured them that contact with these white men would result in death, in the destruction of the Indians, and by the most horrible processes of disease and misery. He thundered and he pleaded. The Indians smoked and reflected. Then they spoke through old Crowfoot:

"We have listened. We will keep upon our reservation. We will not go to see the railroad."

But Father Lacombe doubted still, and yet more profoundly was he convinced of the ruin of the tribe should the "children," as he sagely calls all Indians, disobey him. So once again he went to the reserve, and gathered the c[59]hief and the headmen, and warned them of the soulless, diabolical, selfish instincts of the white men. Again the grave warriors promised to obey him.

The railroad laborers came with camps and money and liquors and numbers, and the prairie thundered the echoes of their sledge-hammer strokes. And one morning the old priest looked out of the window of his bare bedroom and saw curling wisps of gray smoke ascending from a score of tepees on the hill beside Calgary.[1] Angry, amazed, he went to his doorway and opened it, and there upon the ground sat some of the headmen and the old men, with bowed heads, ashamed. Fancy the priest's wrath and his questions! Note how wisely he chose the name of children for them, when I tell you that their spokesman at last answered with the excuse that the buffaloes were gone, and food was hard to get, and the white men brought money which the squaws could get. And what is the end? There are always tepees on the hills now beside every settlement near the Blackfoot reservation. And one old missionary lifted his trembling forefinger towards the sky, when I was there, and said: "Mark me. In fifteen years there will not be a full-blooded Indian alive on the Canadian prairie—not one."

Through all that revolutionary railroad building and the rush of new settlers, Father Lacombe and Crowfoot kept the Indians from war, and even from depredations and f[60]rom murder. When the half-breeds arose under Riel, and every Indian looked to his rifle and his knife, and when the mutterings that preface the war-cry sounded in every lodge, Father Lacombe made Crowfoot pledge his word that the Indians should not rise. The priest represented the Government on these occasions. The Canadian statesmen recognize the value of his services. He is the great authority on Indian matters beyond our border; the ambassador to and spokesman for the Indians.

But Father Lacombe is more than that. He is the deepest student of the Indian languages that Canada possesses. The revised edition of Bishop Barager's Grammar of the Ochipwe Language bears these words upon its title-page: "Revised by the Rev. Father Lacombe, Oblate Mary Immaculate, 1878." He is the author of the authoritative Dictionnaire et Grammaire de la Langue Crise, the dictionary of the Cree dialect published in 1874. He has compiled just such another monument to the Blackfoot language, and will soon publish it, if he has not done so already. He is in constant correspondence with our Smithsonian Institution; he is famous to all who study the Indian; he is beloved or admired throughout Canada.