Illustrated by ASHMAN

Illustrated by ASHMANThe Project Gutenberg EBook of Zen, by Jerome Bixby This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Zen Author: Jerome Bixby Illustrator: William Ashman Release Date: August 21, 2009 [EBook #29750] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ZEN *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Stephen Blundell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Because they were so likable and intelligent and adaptable—they were vastly dangerous!

Illustrated by ASHMAN

Illustrated by ASHMANIt's difficult, when you're on one of the asteroids, to keep from tripping, because it's almost impossible to keep your eyes on the ground. They never got around to putting portholes in spaceships, you know—unnecessary when you're flying by GB, and psychologically inadvisable, besides—so an asteroid is about the only place, apart from Luna, where you can really see the stars.

There are so many stars in an asteroid sky that they look like clouds; like massive, heaped-up silver clouds floating slowly around the inner surface of the vast ebony sphere that surrounds you and your tiny foothold. They are near enough to touch, and you want to touch them, but they are so frighteningly far away ... and so beautiful: there's nothing in creation half so beautiful as an asteroid sky.

You don't want to look down, naturally.

I had left the Lucky Pierre to search for fossils (I'm David Koontz, the Lucky Pierre's paleontologist). Somewhere off in the darkness on either side of me were Joe Hargraves, gadgeting for mineral deposits, and Ed Reiss, hopefully on the lookout for anything alive. The Lucky Pierre was back of us, her body out of sight behind a low black ridge, only her gleaming nose poking above like a porpoise coming up for air. When I looked back, I could see, along the jagged rim of the ridge, the busy reflected flickerings of the bubble-camp the techs were throwing together. Otherwise all was black, except for our blue-white torch beams that darted here and there over the gritty, rocky surface.

The twenty-nine of us were E.T.I. Team 17, whose assignment was the asteroids. We were four years and three months out of Terra, and we'd reached Vesta right on schedule. Ten minutes after landing, we had known that the clod was part of the crust of Planet X—or Sorn, to give it its right name—one of the few such parts that hadn't been blown clean out of the Solar System.

That made Vesta extra-special. It meant settling down for a while. It meant a careful, months-long scrutiny of Vesta's every square inch and a lot of her cubic ones, especially by the life-scientists. Fossils, artifacts, animate life ... a surface chunk of Sorn might harbor any of these, or all. Some we'd tackled already had a few.

In a day or so, of course, we'd have the one-man beetles and crewboats out, and the floodlights orbiting overhead, and Vesta would be as exposed to us as a molecule on a microscreen. Then work would start in earnest. But in the meantime—and as usual—Hargraves, Reiss and I were out prowling, our weighted boots clomping along in darkness. Captain Feldman had long ago given up trying to keep his science-minded charges from galloping off alone like this. In spite of being a military man, Feld's a nice guy; he just shrugs and says, "Scientists!" when we appear brightly at the airlock, waiting to be let out.

So the three of us went our separate ways, and soon were out of sight of one another. Ed Reiss, the biologist, was looking hardest for animate life, naturally.

But I found it.

I had crossed a long, rounded expanse of rock—lava, wonderfully colored—and was descending into a boulder-cluttered pocket. I was nearing the "bottom" of the chunk, the part that had been the deepest beneath Sorn's surface before the blow-up. It was the likeliest place to look for fossils.

But instead of looking for fossils, my eyes kept rising to those incredible stars. You get that way particularly after several weeks of living in steel; and it was lucky that I got that way this time, or I might have missed the Zen.

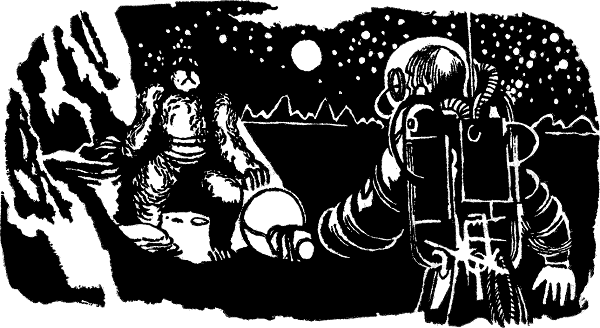

My feet tangled with a rock. I started a slow, light-gravity fall, and looked down to catch my balance. My torch beam flickered across a small, red-furred teddy-bear shape. The light passed on. I brought it sharply back to target.

My hair did not stand on end, regardless of what you've heard me quoted as saying. Why should it have, when I already knew Yurt so well—considered him, in fact, one of my closest friends?

The Zen was standing by a rock, one paw resting on it, ears cocked forward, its stubby hind legs braced ready to launch it into flight. Big yellow eyes blinked unemotionally at the glare of the torch, and I cut down its brilliance with a twist of the polarizer lens.

The creature stared at me, looking ready to jump halfway to Mars or straight at me if I made a wrong move.

I addressed it in its own language, clucking my tongue and whistling through my teeth: "Suh, Zen—"

In the blue-white light of the torch, the Zen shivered. It didn't say anything. I thought I knew why. Three thousand years of darkness and silence ...

I said, "I won't hurt you," again speaking in its own language.

The Zen moved away from the rock, but not away from me. It came a little closer, actually, and peered up at my helmeted, mirror-glassed head—unmistakably the seat of intelligence, it appears, of any race anywhere. Its mouth, almost human-shaped, worked; finally words came. It hadn't spoken, except to itself, for three thousand years.

"You ... are not Zen," it said. "Why—how do you speak Zennacai?"

It took me a couple of seconds to untangle the squeaking syllables and get any sense out of them. What I had already said to it were stock phrases that Yurt had taught me; I knew still more, but I couldn't speak Zennacai fluently by any means. Keep this in mind, by the way: I barely knew the language, and the Zen could barely remember it. To save space, the following dialogue is reproduced without bumblings, blank stares and What-did-you-says? In reality, our talk lasted over an hour.

"I am an Earthman," I said. Through my earphones, when I spoke, I could faintly hear my own voice as the Zen must have heard it in Vesta's all but nonexistent atmosphere: tiny, metallic, cricket-like.

"Eert ... mn?"

I pointed at the sky, the incredible sky. "From out there. From another world."

It thought about that for a while. I waited. We already knew that the Zens had been better astronomers at their peak than we were right now, even though they'd never mastered space travel; so I didn't expect this one to boggle at the notion of creatures from another world. It didn't. Finally it nodded, and I thought, as I had often before, how curious it was that this gesture should be common to Earthmen and Zen.

"So. Eert-mn," it said. "And you know what I am?"

When I understood, I nodded, too. Then I said, "Yes," realizing that the nod wasn't visible through the one-way glass of my helmet.

"I am—last of Zen," it said.

I said nothing. I was studying it closely, looking for the features which Yurt had described to us: the lighter red fur of arms and neck, the peculiar formation of flesh and horn on the lower abdomen. They were there. From the coloring, I knew this Zen was a female.

The mouth worked again—not with emotion, I knew, but with the unfamiliar act of speaking. "I have been here for—for—" she hesitated—"I don't know. For five hundred of my years."

"For about three thousand of mine," I told her.

And then blank astonishment sank home in me—astonishment at the last two words of her remark. I was already familiar with the Zens' enormous intelligence, knowing Yurt as I did ... but imagine thinking to qualify years with my when just out of nowhere a visitor from another planetary orbit pops up! And there had been no special stress given the distinction, just clear, precise thinking, like Yurt's.

I added, still a little awed: "We know how long ago your world died."

"I was child then," she said, "I don't know—what happened. I have wondered." She looked up at my steel-and-glass face; I must have seemed like a giant. Well, I suppose I was. "This—what we are on—was part of Sorn, I know. Was it—" She fumbled for a word—"was it atom explosion?"

I told her how Sorn had gotten careless with its hydrogen atoms and had blown itself over half of creation. (This the E.T.I. Teams had surmised from scientific records found on Eros, as well as from geophysical evidence scattered throughout the other bodies.)

"I was child," she said again after a moment. "But I remember—I remember things different from this. Air ... heat ... light ... how do I live here?"

Again I felt amazement at its intelligence; (and it suddenly occurred to me that astronomy and nuclear physics must have been taught in Sorn's "elementary schools"—else that my years and atom explosion would have been all but impossible). And now this old, old creature, remembering back three thousand years to childhood—probably to those "elementary schools"—remembering, and defining the differences in environment between then and now; and more, wondering at its existence in the different now—

And then I got my own thinking straightened out. I recalled some of the things we had learned about the Zen.

Their average lifespan had been 12,000 years or a little over. So the Zen before me was, by our standards, about twenty-five years old. Nothing at all strange about remembering, when you are twenty-five, the things that happened to you when you were seven ...

But the Zen's question, even my rationalization of my reaction to it, had given me a chill. Here was no cuddly teddy bear.

This creature had been born before Christ!

She had been alone for three thousand years, on a chip of bone from her dead world beneath a sepulchre of stars. The last and greatest Martian civilization, the L'hrai, had risen and fallen in her lifetime. And she was twenty-five years old.

"How do I live here?" she asked again.

I got back into my own framework of temporal reference, so to speak, and began explaining to a Zen what a Zen was. (I found out later from Yurt that biology, for the reasons which follow, was one of the most difficult studies; so difficult that nuclear physics actually preceded it!) I told her that the Zen had been, all evidence indicated, the toughest, hardest, longest-lived creatures God had ever cooked up: practically independent of their environment, no special ecological niche; just raw, stubborn, tenacious life, developed to a fantastic extreme—a greater force of life than any other known, one that could exist almost anywhere under practically any conditions—even floating in midspace, which, asteroid or no, this Zen was doing right now.

The Zens breathed, all right, but it was nothing they'd had to do in order to live. It gave them nothing their incredible metabolism couldn't scrounge up out of rock or cosmic rays or interstellar gas or simply do without for a few thousand years. If the human body is a furnace, then the Zen body is a feeder pile. Maybe that, I thought, was what evolution always worked toward.

"Please, will you kill me?" the Zen said.

I'd been expecting that. Two years ago, on the bleak surface of Eros, Yurt had asked Engstrom to do the same thing. But I asked, "Why?" although I knew what the answer would be, too.

The Zen looked up at me. She was exhibiting every ounce of emotion a Zen is capable of, which is a lot; and I could recognize it, but not in any familiar terms. A tiny motion here, a quiver there, but very quiet and still for the most part. And that was the violent expression: restraint. Yurt, after two years of living with us, still couldn't understand why we found this confusing.

Difficult, aliens—or being alien.

"I've tried so often to do it myself," the Zen said softly. "But I can't. I can't even hurt myself. Why do I want you to kill me?" She was even quieter. Maybe she was crying. "I'm alone. Five hundred years, Eert-mn—not too long. I'm still young. But what good is it—life—when there are no other Zen?"

"How do you know there are no other Zen?"

"There are no others," she said almost inaudibly. I suppose a human girl might have shrieked it.

A child, I thought, when your world blew up. And you survived. Now you're a young three-thousand-year-old woman ... uneducated, afraid, probably crawling with neuroses. Even so, in your thousand-year terms, young lady, you're not too old to change.

"Will you kill me?" she asked again.

And suddenly I was having one of those eye-popping third-row-center views of the whole scene: the enormous, beautiful sky; the dead clod, Vesta; the little creature who stood there staring at me—the brilliant-ignorant, humanlike-alien, old-young creature who was asking me to kill her.

For a moment the human quality of her thinking terrified me ... the feeling you might have waking up some night and finding your pet puppy sitting on your chest, looking at you with wise eyes and white fangs gleaming ...

Then I thought of Yurt—smart, friendly Yurt, who had learned to laugh and wisecrack—and I came out of the jeebies. I realized that here was only a sick girl, no tiny monster. And if she were as resilient as Yurt ... well, it was his problem. He'd probably pull her through.

But I didn't pick her up. I made no attempt to take her back to the ship. Her tiny white teeth and tiny yellow claws were harder than steel; and she was, I knew, unbelievably strong for her size. If she got suspicious or decided to throw a phobic tizzy, she could scatter shreds of me over a square acre of Vesta in less time than it would take me to yelp.

"Will you—" she began again.

I tried shakily, "Hell, no. Wait here." Then I had to translate it.

I went back to the Lucky Pierre and got Yurt. We could do without him, even though he had been a big help. We'd taught him a lot—he'd been a child at the blow-up, too—and he'd taught us a lot. But this was more important, of course.

When I told him what had happened, he was very quiet; crying, perhaps, just like a human being, with happiness.

Cap Feldman asked me what was up, and I told him, and he said, "Well, I'll be blessed!"

I said, "Yurt, are you sure you want us to keep hands off ... just go off and leave you?"

"Yes, please."

Feldman said, "Well, I'll be blessed."

Yurt, who spoke excellent English, said, "Bless you all."

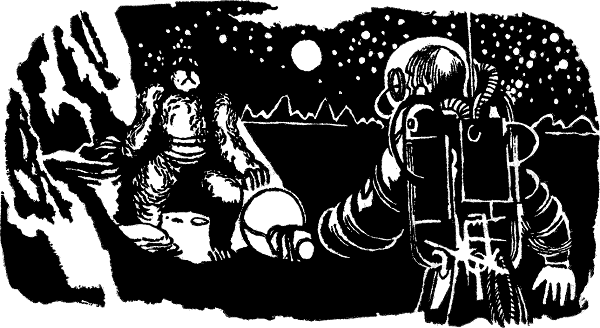

I took him back to where the female waited. From the ridge, I knew, the entire crew was watching through binocs. I set him down, and he fell to studying her intently.

"I am not a Zen," I told her, giving my torch full brilliance for the crew's sake, "but Yurt here is. Do you see ... I mean, do you know what you look like?"

She said, "I can see enough of my own body to—and—yes ..."

"Yurt," I said, "here's the female we thought we might find. Take over."

Yurt's eyes were fastened on the girl.

"What—do I do now?" she whispered worriedly.

"I'm afraid that's something only a Zen would know," I told her, smiling inside my helmet. "I'm not a Zen. Yurt is."

She turned to him. "You will tell me?"

"If it becomes necessary." He moved closer to her, not even looking back to talk to me. "Give us some time to get acquainted, will you, Dave? And you might leave some supplies and a bubble at the camp when you move on, just to make things pleasanter."

By this time he had reached the female. They were as still as space, not a sound, not a motion. I wanted to hang around, but I knew how I'd feel if a Zen, say, wouldn't go away if I were the last man alive and had just met the last woman.

I moved my torch off them and headed back for the Lucky Pierre. We all had a drink to the saving of a great race that might have become extinct. Ed Reiss, though, had to do some worrying before he could down his drink.

"What if they don't like each other?" he asked anxiously.

"They don't have much choice," Captain Feldman said, always the realist. "Why do homely women fight for jobs on the most isolated space outposts?"

Reiss grinned. "That's right. They look awful good after a year or two in space."

"Make that twenty-five by Zen standards or three thousand by ours," said Joe Hargraves, "and I'll bet they look beautiful to each other."

We decided to drop our investigation of Vesta for the time being, and come back to it after the honeymoon.

Six months later, when we returned, there were twelve hundred Zen on Vesta!

Captain Feldman was a realist but he was also a deeply moral man. He went to Yurt and said, "It's indecent! Couldn't the two of you control yourselves at least a little? Twelve hundred kids!"

"We were rather surprised ourselves," Yurt said complacently. "But this seems to be how Zen reproduce. Can you have only half a child?"

Naturally, Feld got the authorities to quarantine Vesta. Good God, the Zen could push us clear out of the Solar System in a couple of generations!

I don't think they would, but you can't take such chances, can you?

—JEROME BIXBY

Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Galaxy Science Fiction October 1952. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed. Minor spelling and typographical errors have been corrected without note.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Zen, by Jerome Bixby

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ZEN ***

***** This file should be named 29750-h.htm or 29750-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/2/9/7/5/29750/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Stephen Blundell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.net/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.net),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.net

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.