Project Gutenberg's From the Valley of the Missing, by Grace Miller White

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: From the Valley of the Missing

Author: Grace Miller White

Release Date: April 1, 2006 [EBook #18093]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FROM THE VALLEY OF THE MISSING ***

Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

FROM THE VALLEY

OF THE MISSING

BY

GRACE MILLER WHITE

AUTHOR OF

TESS OF THE STORM COUNTRY

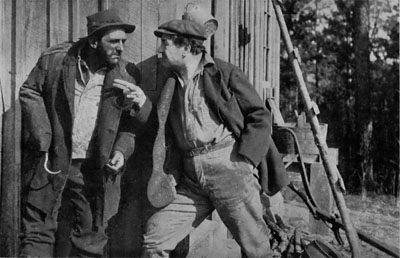

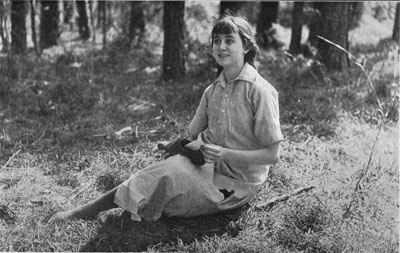

ILLUSTRATED WITH SCENES FROM THE PHOTO-PLAY

PRODUCED AND COPYRIGHTED BY THE FOX FILM CORPORATION

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS :

New York

Copyright, 1911, by

W. J. WYATT & COMPANY

Published, August, 1911

Table of Contents

| CHAPTER ONE | 1 |

| CHAPTER TWO | 10 |

| CHAPTER THREE | 18 |

| CHAPTER FOUR | 23 |

| CHAPTER FIVE | 30 |

| CHAPTER SIX | 45 |

| CHAPTER SEVEN | 52 |

| CHAPTER EIGHT | 59 |

| CHAPTER NINE | 65 |

| CHAPTER TEN | 74 |

| CHAPTER ELEVEN | 88 |

| CHAPTER TWELVE | 99 |

| CHAPTER THIRTEEN | 105 |

| CHAPTER FOURTEEN | 120 |

| CHAPTER FIFTEEN | 126 |

| CHAPTER SIXTEEN | 136 |

| CHAPTER SEVENTEEN | 144 |

| CHAPTER EIGHTEEN | 152 |

| CHAPTER NINETEEN | 162 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY | 173 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE | 180 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO | 185 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE | 194 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR | 202 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE | 214 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX | 226 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN | 234 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT | 241 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE | 256 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY | 263 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE | 271 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO | 277 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE | 282 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR | 289 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE | 300 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX | 307 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN | 311 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT | 326 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE | 335 |

[Pg 1]

“FROM THE VALLEY OF THE MISSING”

CHAPTER ONE

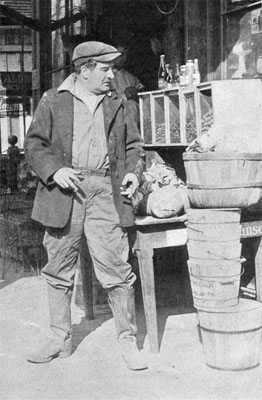

One afternoon in late October four lean mules, with stringy muscles

dragging over their bones, stretched long legs at the whirring of their

master's whip. The canalman was a short, ill-favored brute, with coarse

red hair and freckled skin. His nose, thickened by drink, threatened the

short upper lip with obliteration. Straight from ear to ear, deep under

his chin, was a zigzag scar made by a razor in his boyhood days, and

under emotion the injured throat became convulsed at times, causing his

words to be unintelligible. The red flannel shirt, patched with colors

of lighter shades, lay open to the shoulders, showing the dark, rough

skin.

"Git—git up!" he stuttered; and for some minutes the boat moved

silently, save for the swish of the water and the patter of the mules'

feet on the narrow path by the river.

From the small living-room at one end of the boat came the crooning of a

woman's voice, a girlish voice, which rose and fell without tune or

rhythm. Suddenly the mules came to a standstill with a "Whoa thar!"

"Pole me out a drink, Scraggy," bawled the man, "and put a big snack of

whisky in it—see?"

The boulder-shaped head shot forward in command as[Pg 2] he spoke. And he

held the reins in his left hand, turning squarely toward the scow.

Pushing out a dark, rusty, steel hook over which swung a ragged

coat-sleeve, he displayed the stump of a short arm.

As the woman appeared at the bow of the boat with a long stick on the

end of which hung a bucket, Lem Crabbe wound the reins about the steel

hook and took the proffered pail in the fingers of his left hand.

"Ye drink too much whisky, Lem," called the woman. "Ye've had as many as

twenty swigs today. Ye'll get no more till we reaches the dock—see?"

To this Lem did not reply. His shrewd eyes traveled up and down the

girlish figure in evil meaning. His thick lips opened, and the swarthy

cheeks went awry in a grimace. Before the hideous spasm of his silent

merriment the woman who loved him paled, and turned away with a shudder.

She slouched down the short flight of steps, and the man, with a grin,

malicious and cunning, lifted the tin pail to his lips.

"It's time for her to go," he muttered as he wiped his mouth, "it's time

for her to go! Git back here, Scraggy, and take this 'ere drink cup!"

This time the woman appeared with a fat baby in her arms. Mechanically

she unloosened the pail from the bent nail on the end of the pole and

put it down, watching the man as he unwound the reins from the hook.

Again the long-eared animals stretched their muscles at his hoarse

command. He paid no more attention to the woman, who, seated on a pile

of planks, was eying the square end of the boat. She drew a plaid shawl

close up under the baby's chin and threaded her listless fingers through

his dark curls. Scraggy's thin hair was drawn back from her wan face,

and her narrow shoulders were bowed with burdens too heavy for her

years; but she hugged the little creature sleeping on her breast, and

still[Pg 3] kept her eyes upon the scene. Beyond she could see the smoke

rising from the buildings in the city of Albany, where they were to draw

the boat up for the night. On each side of the river bank, behind clumps

of trees, stood the mansions of those men for whom, according to Scraggy

Peterson's belief, the world had been made. Finally her gaze dropped to

the scow, where little rivers of water made crooked paths across the

deck. Piles of planks reared high at her back, and edged the scow with

the squareness of a room. Scraggy knew that hauling lumber was but the

cover for a darker trade. Yet as she glanced at the stolid, indifferent

man trudging behind the mules a lovelight sprang into her eyes.

Later, by an hour, the mules came to a halt at Lem's order.

"Throw down that gangplank, Scraggy," stammered Crabbe, "and put the

brat below! I want to get these here mules in. The storm'll be here in

any minute."

Obediently the woman hastened to comply, and soon the tired mules

munched their suppers, their long faces filling the window-gaps of the

stable.

Lem Crabbe followed the woman down the scow-steps amid gusty howls of

the wind, and the night fell over the city and the black, winding river.

The man ate his supper in silence, furtively casting his eyes now and

then upon the slender figure of the woman. He chewed fast, uttering no

word, and the creaking of the heavy jaws and the smacking of the coarse

lips were the only sounds to be heard after the woman had taken her

place at the table. Scraggy dared not yet begin to eat; for something

new in her master's manner filled her with sudden fear. By sitting very

quietly, she hoped to keep his attention upon his plate, and after he

had eaten he would go to bed. She was aroused from this thought by the

feeble whimper of her child in the tiny room of the scow's bow.

Although[Pg 4] the woman heard, she made no move to answer the weak summons.

She rose languidly as the child began to cry more loudly; but a command

from Lem stopped her.

"Set down!" he said.

"The brat's a wailin'," replied Scraggy hoarsely.

"Set down, and let him wail!" shouted Lem.

Scraggy sank unnerved into the chair, gazing at him with terrified eyes.

"Why, Lem, he's too little to cry overmuch."

"Keep a settin', I say! Let him yap!"

For the second time that day Scraggy's face shaded to the color of

ashes, and her gaze dropped before the fierce eyes directed upon her.

"Ye said more'n once, Scraggy," began Lem, "that I wasn't to drink no

more whisky. Whose money pays for what I drink? That's what I want ye to

tell me!"

"Yer money, Lem dear."

"And ye say as how I couldn't drink what I pay for?"

"Yep, I has said it," was the timid answer. "Ye drink too much—that's

what ye do! Ye ain't no mind left, ye ain't! And it makes ye ugly, so it

does!"

"Be it any of yer business?" demanded Lem insultingly, as he filled his

mouth with a piece of brown bread. After washing it down with a drink of

whisky, he finished, "Ye ain't no relation to me, be ye?"

The thin face hung over the tin plate.

"Ye ain't married to me, be ye?"

And, while a giant pain gnawed at her heart, she shook her head.

"Then what right has ye got to tell me what to do? Shut up or get

out—ye see?"

He closed his jaw with a vicious snap, resting his half-dazed head on

his mutilated arm. Louder came the[Pg 5] baby's cries from the back room.

Thinking Lem had ended his tirade, Scraggy made a motion to rise.

"Set still!" growled Crabbe.

"Can't I get the brat, Lemmy?" she pleaded. "He's likely to fall offen

the bed."

"Let him fall. What do I care? I want to tell ye somethin'. I didn't

bring ye here to this boat to boss me, ye see? Ye keep yer mouth shet

'bout things what ye don't like. Ye're in my way, anyhow."

"Ye mean, Lemmy, as how I has to leave ye?"

Crabbe regarded the appealing face soddenly before answering. "Yep,

that's what I mean. I'm tired of a woman allers a snoopin' around, and a

hundred times more tired of the brat."

"But he's yer own," cried the woman, "and ye did say as how ye'd marry

me for his sake! Didn't ye say it, Lem? He ain't nothin' but a baby, an'

he don't cry much. Will ye let me an' him stay, Deary?"

"Ye can stay tonight; but tomorry ye go, and I don't give a hell where,

so long as ye leave this here scow, an' I'm a tellin' ye this—" He

halted with an exasperated gesture. "Go an' get that kid an' shet his

everlastin' clack!"

Scraggy bounded into the inner room, and, once out of sight of the

watchful eyes of Lem, snatched up the infant and pressed her lips

passionately to the rosy skin.

"Yer mammy'll allers love ye, little 'un, allers, allers, no matter what

yer pappy does!"

She whispered this under her breath; then, dragging the red shawl about

her shoulders, appeared in the living-room with the child hidden from

view.

"An' I'll tell ye somethin' else, too," burst in Lem, pulling out a

corncob pipe: "that it ain't none of yer business if I steal or if I

don't. I was born a thief, as[Pg 6] I told ye many a time, and last night ye

made Lon Cronk and Eli mad as hell by chippin' in."

"They be bad men," broke in the woman, "and ye know—"

"I know ye're a damn blat-heels, and I know more'n that: that yer own

pappy ain't no angel, and ye needn't be a sayin' my friends ain't no

right here—ye see? They be—"

"They be thieves and liars, too," interrupted Scraggy, allowing the

sleeping babe to sink to her knees, "and the prison's allers a yawnin'

for 'em!"

"Wall, I ain't a runnin' this boat for fun," drawled Lem, "nor for to

draw lumber for any ole guy in Albany. Ye know that I draw it jest to

hide my trade, and if, after ye leave here, ye open yer head to tell

what ye've seen, ye'll get this—ye see?" He held up the hooked arm

menacingly. "Ye've seen me rip up many a man with it, ain't ye,

Scraggy?"

"Yep."

"And I ain't got nothin' ag'in' rippin' up a woman, nuther. So, when ye

go back to yer pa in Ithacy, keep yer mouth shet.... Will ye let up that

there cryin'?"

Suppressing her tears, Scraggy shoved back a little from the table. "I

love ye, Lem," she choked, "and, if ye let me stay, I'll do whatever ye

say. I won't talk nothin' 'bout drink nor stealin'. If I go ye'll get

another woman! I know ye can't live on this here scow without no woman."

"And that ain't none of yer business, nuther—ye hear?" Lem grunted,

settling deep into his chair, with an oath. "I'll get all the women in

Albany, if I want 'em! I don't never want none of yer lovin' any more!"

During this bitter insult a storm-cloud broke overhead, sending sheets

of water into the river. The wind howled above Crabbe's words, and he

brought out the last of his[Pg 7] sentence in a higher key. Suddenly the

shrill whistle of a yacht brought the drunken man to his feet.

"It's some 'un alone in trouble," he muttered. But his tones were not so

low as to escape the woman.

"Ye won't do no robbin' tonight, Deary—not tonight, will ye, Lem?

'Cause it's the baby's birthday."

Crabbe flung his squat body about toward the girl. "Shet up about that

brat!" he growled. "I don't care 'bout no birthdays. I'll steal, if the

man has anything and he's alone. I'll kill him like this, if he don't

give up. Do ye want to see how I'd kill him?"

His eyes blazing with fire, he lifted the steel hook, brandished it in

the air, and brought it down close to the thin, drawn face.

Scraggy, uttering a cry, sprang to her feet. "Lemmy, Lemmy, I love ye,

and the brat loves ye, too! He'll grin at ye any ole day when ye cluck

at him. And I teached him to say 'Daddy,' to surprise ye on his

birthday. Will ye list to him—will ye?"

In her eagerness to take his attention from the shrieking yacht, now

close to the scow, Scraggy advanced toward the swaying man. She tried to

lift brave eyes to his face; but they were filled with tears as they met

his drunken, shifting look.

"Lem, Lemmy dear," she pleaded, "we love ye, both the brat an' me! He

can say 'Daddy'—"

"Git out of my way, git out! Some'n' be a callin'. Git out, I say!"

"Not yet, not yet—don't go yet, Deary.... Deary! Wait till the kid says

'Daddy.'" She held out the rosy babe, pushing him almost under Lem's

chin. "Look at him, Lemmy! Ain't—he—sweet? He's yer own pretty

boy-brat, and—"

Her loving plea was cut short; for the man, with a vicious growl, raised

his stumped arm, and the sharp part[Pg 8] of the hook scraped the skin from

her hollow cheek. It paused an instant on the level of her chin, then

descended into the upturned chest of the child. With a scream, Scraggy

dragged the boy back, and a wail rose from the tiny lips. Crabbe turned,

cursing audibly, and stumbled up the steps to the stern of the boat. The

woman heard him fall in his drunken stupor, and listened again and again

for him to rise. Her face was white and rigid as she stopped the flow of

blood that drenched the infant's coarse frock. Then, realizing the

danger both she and the child were in, since in all likelihood Lem would

sleep but a few minutes, she slid open the window and looked out upon

the dark river in search of help. Splashes of rain pelted her face,

while a gust of wind caused the scow to creak dismally. Scraggy could

see no human being, only the lights of Albany blinking dimly through the

raging storm. Another shrieking whistle warned her that the yacht was

still near. Sailors' voices shouted orders, followed by the chug, chug,

chug of an engine reversed.

But, in spite of the efforts of the engineer, the wind swung the small

craft sidewise against the scow, and, stupefied, Scraggy found herself

gazing into the face of another woman who was peering from the launch's

window. It was a small, beautiful face shrouded with golden hair, the

large blue eyes widened with terror. For a brief instant the two women

eyed each other. Just then the drunken man above rose and called

Scraggy's name with an oath. She heard him stumbling about, trying to

find the stairs, muttering invectives against herself and her child.

Scraggy looked down upon the little boy's face, twisted with pain. She

placed her fingers under his chin, closed the tiny jaws, and wrapped the

shawl about the dark head. Without a moment's indecision, she thrust him

through the window-space and said:

"Be ye a good woman, lady, a good woman?"[Pg 9]

The owner of the golden head drew back as if afraid.

"Ye wouldn't hurt a little 'un—a sick brat? He—he's been hooked. And

it's his birthday. Take him, 'cause he'll die if ye don't!"

Moved to a sense of pity, the light-haired woman extended two slender

white hands to receive the human bundle, struggling in pain under the

muffling shawl.

"He's a dyin'!" gasped Scraggy. "His pappy's a hatin' him! Give him warm

milk—"

Again the yacht's whistle shrieked hoarsely, drowning her last words. As

the stern of the little boat swung round, Scraggy read, stamped in black

letters upon it:

Harold Brimbecomb,

Tarrytown-on-the-Hudson,

New York.

The yacht shot away up the river, and was lost to the dull eyes that

continued peering for a last glimpse of the phantom-like boat that had

snatched her dying treasure from her. Then, at last, the stricken woman

turned, alone, to meet Lem Crabbe.

"Where's that brat?" he demanded in a thick voice.

"I throwed him in the river," declared the mother. "He were dead. Yer

hook killed him, Lem. He's gone!"

"I'll kill his mammy, too!" muttered Crabbe. "Git ye here—here—down

here—on the floor!"

His throat worked painfully as he threw the threatening words at her;

they mingled harshly with the snarling of the wind and the sonorous

rumble of the river. So great was Scraggy's fright that she sped round

the wooden table to escape the frenzied man. Taking the steps in two

bounds, she sprang to the deck like a cat, thence to the bank, and sped

away into the rain, with Lem's cries and curses ringing in her ears.

Five years later the Monarch was drawn up to the east bank of the Erie

Canal at Syracuse. It was past midnight, and with the exception of those

on Lem Crabbe's scow the occupants of all the long line of boats were

sleeping. Three men sat silently working in the living-room of the boat.

Lem Crabbe, Silent Lon Cronk, and his brother Eli, Cayuga Lake

squatters, were the workers. At one end of the room hung a broken iron

kettle. Into this Eli Cronk was dropping bits of gold which he cut from

baubles taken from a basket. Crabbe, his short legs drawn up under his

body, held a pair of pliers in his left hand, while caught firmly in the

hook was a child's tiny pin. From this he tore the small jewels, threw

them into a tin cup, and passed the setting on to Eli. The other man,

taciturn and fierce, was flattening out by means of strong pressers

several gold rings and bracelets. The three had worked for many hours

with scarcely a word spoken, with scarcely a recognition of one another.

Of a sudden Eli Cronk raised his head and said, "Lem, Scraggy was to

Mammy's t'other day."

"I didn't know ye'd been to Ithacy?" Lem made the statement a question.

"Yep, I went to see Mammy, and she says as how Scraggy's pappy were

dead, and as how the gal's teched in here." His words were low, and he

raised his forefinger to his head significantly.

"She ain't allers a stayin' in the squatter country nuther," he pursued.

"She takes that damn ugly cat of her'n and scoots away for a time. And

none of 'em up[Pg 11] there don't know where she goes. Hones' Injun, don't she

never come about this here scow, Lem?"

"Hones' Injun," replied Lem laconically, without looking up from his

work.

Presently Eli continued:

"Mammy says as how the winter's comin', and some 'un ought to look out

for Scraggy. She goes 'bout the lake doin' nothin' but hollerin' like a

hoot-owl, and she don't have enough to eat. But she's been gone now

goin' on two weeks, disappearin' like she's been doin' for a few years

back. Scraggy allers says she has bats in her head."

"So she has bats," muttered Lem, "and she allers had 'em, and that's why

I made her beat it. I didn't want no woman 'bout me for good and all."

Lem Crabbe lifted his head and glanced toward the small window

overlooking the dark canal. He had always feared the crazy

squatter-woman whom he had wrecked by his brutality.

"I says that I don't want no woman round me for all time," he repeated.

The third man raised his right shoulder at that; but sank into a heap

again, working more assiduously. The slight trembling of his body was

the only evidence he gave that he had heard Crabbe's words. Snip, snip,

snip! went the bits of gold into the kettle, until Eli spoke again.

"Ye can't tell me that ye ain't goin' never to get married, Lem?"

Crabbe lifted his hooked arm viciously. "I ain't said nothin' like that.

I says as how Scraggy can keep away from my scow."

"Don't she never come here no more?" asked Eli in disbelief.

"Nope, not after them three beatin's I give her. She kept a comin', and

I had to wallop her. I'd do it again if she snoops 'bout here."[Pg 12]

"Ye beat her up well, didn't ye, Lem? And she telled Mammy that yer brat

were drowned one night in the river. Were it, Lem?"

There was an expectant pause between his first and last questions, and

Lem waited almost as long before he grunted:

"Yep."

"Did ye throw it in when ye was drunk?"

"Nope, he jest fell in—that's all."

"I guess that last beatin' ye give Scraggy made her batty. Mam says that

she ain't no more sense than her cat."

"Let her keep to hum then, and she won't get beat. I don't do no runnin'

after her!"

Again there came a space of time during which Eli and Lem worked in

silence. From far away in the city there came the sound of the fire

whistle, followed by the ringing of bells. But not one of the men ceased

his clipping to satisfy any curiosity he might have had.

Suddenly Lem Crabbe spoke louder than he had before that evening.

"Women ain't no good, nohow! They don't love no men, and men don't love

them. What's the good of havin' 'em round to feed and to bother a feller

'bout drinkin' an' things? Less a man sees of 'em the better!"

The third man, Silent Lon Cronk, sunk lower at his work, even more

fiercely flattening the gemless rings under the pressers. After a few

moments he laid down his tools and began to stretch his long legs,

scraping into a cup the bits of gold from his lap.

"I've been goin' to ask ye fellers somethin' for a long time. Might as

well now as any other night, eh?"

"Yep," replied Eli eagerly.

"'Tain't nothin' that will take any money out yer pockets; 'twill put it

in, more likely. We've been stealin'[Pg 13] together for how long, Lem? How

long we been pals?"

"Nigh onto ten years, I'm thinkin'. It were that year that Tilly

Jacobson got burned, weren't it?"

"Yep, for ten years," replied Lon, ignoring Lem's last query, "and we've

allers been hones' with each other. I've been hones' with both of ye,

and ye've been hones' with me. Eh?"

"Yep."

"Lem, do ye want all the swag in this here room, only a sharin' up with

Eli, without havin' to share and share alike with me?"

A small jewel bounded from the steel hook, and the pliers fell from

Lem's fingers. Eli dropped back upon his bare feet.

"What's in the wind?" demanded Lem.

"Only want ye to help me with a job some night that won't be nothin' to

nuther of ye. But it's all to me. Will ye?"

Lem wriggled nearer on the floor. "Ye mean stealin', Lon?" he demanded.

"Yep."

"And we ain't to share up with it?"

"Nope; but ye're to have all that's in this here room. If I tell ye,

will ye help?"

Crabbe looked at Eli, and a furtive look was shot back. Each was afraid

of the other; but for the big, gloomy man before them they had vast

respect.

"What be ye goin' to steal, Lon? Tell us before we say we'll help."

"Kids," muttered Lon moodily.

"Live kids?" asked Eli, in great surprise.

"Yep, live ones. What do I want with dead ones? Will ye help?"

"Can't see no good a swipin' kids. What do ye want with 'em?"[Pg 14]

"I'll tell ye if ye sit up and listen to me."

Crabbe dropped his hooked arm and leaned against the wall. Eli lighted a

pipe. A mysterious change had passed over Silent Lon's face. The blue

eyes glowed out from under a massive brow, and a mouth cruel and

vindictive set firm-jawed over decayed teeth.

"I'll tell ye this much for all time, Lem Crabbe: that ye lied when ye

said that no woman could love no man—ye lied, I say!"

So fierce had he become that the man with the hook drew back into the

corner and sat staring sullenly. Eli puffed more vigorously on his pipe.

Lon went on:

"I had a woman oncet," said he, "and she were every bit mine. And she

were little—like this."

The big fellow measured off a space with his hand and, straightening

again, stood against the wall of the scow, his head reaching almost to

the ceiling.

"She were mine, I say, and any man what says she weren't—"

"Where be she?" interrupted Lem curiously.

"Dead," replied Lon, "as dead as if she'd never been alive, as dead as

if she'd never laid ag'in' my heart when I wanted her! God! how I wanted

her!"

"But were she a woman?" asked Lem meditatively.

"Yep, she were a woman, and I married her square, I did!"

Lon stirred his dank black hair ferociously, standing it on end with

horny fingers. "I loved her, Lem Crabbe," he continued hoarsely. "I

loved her, that I know! And ye can let that devilish grin ride on yer

lips when I say it and I don't give a hell; but—but if ye say that she

didn't love me, if ye so much as smile when I say that she died a

callin' me, that she went away lovin' me every[Pg 15] minute, I—I'll rip

offen yer hooked arm and tear out yer in'ards with it!"

He was leaning against the wall no longer. As he spoke, he came closer

to the crouching canalman, his eyes straining from their sockets in

livid hate. But he halted, and presently began to speak in a voice more

subdued.

"But she's dead, and I'm goin' to get even. He killed her, he did,

'cause he wouldn't let me see her, and he's got to go the same way I

went! He's got to tear his hair and call God to curse some 'un he won't

know who! He's got to want his kids like as how I've been wantin'

mine—"

"Ye ain't had no kids, Lon," his brother broke in scoffingly.

"I would a had if he'd a kept his hands to hum and let me see her. But

she were so little an' young-like an' afeard, and I telled her that

night—I telled her when she whispered that she were a goin' to have a

baby, and said as how she couldn't stand bein' hurt—I says, 'Midge

darlin', do it hurt the grass to grow jest 'cause the winds bend it

double? Do it hurt the little birds to bust out of their shells in the

springtime?' And she knowed what I meant, that not even what she were a

thinkin' of could hurt her if I was there close by."

His deep voice sank almost to a whisper, a hard, heavy sob closing his

throat. He shook himself fiercely and continued:

"I took her up close—God! how close I tooked her up! And I telled her

that there wasn't no pain big 'nough to hurt her when I were there—that

even God's finger couldn't tech her afore it went through me. And she

fell to sleep like a bird, a trustin' me, 'cause I said as how there

wasn't goin' to be no hurt. And all the time I knowed I were a lyin'—I

knowed that she'd suffer—"

His voice trailed into silence, the muscles of his dark[Pg 16] face twitching

under the gnawing heart-pain; but after a time he conquered his feelings

and went on:

"Then they comed and took me away for stealin' jest that there week and

sent me up to Auburn prison, and they wouldn't let me stay with her. And

I telled the state's lawyer, Floyd Vandecar, this; I says, 'Vandecar, ye

be a good man, I be a thief, and ye caught me square, ye did. My little

Midge be sick like women is sick sometimes, and she wants me, like every

woman wants her man jest then, an' if ye'll let me see her, to stay a

bit, I'll go up for twice my time.' But he jest laughed till—"

Lon stopped speaking, and neither listener moved. For a moment he

lowered his head to the small boat window and gazed out into the vapors

hanging low over the opposite bank.

Turning again, he backed up to the scow's side and proceeded in a lower

voice:

"When they telled me she were dead, they had to set me in the jacket,

buckled so tight ye could hear my bones crack. The warden ain't got no

blame comin' from me, 'cause I smashed his face afore he'd done tellin'

me. And I felled the keeper like that!" He raised a knotty fist and

thrust it forth. "But it were all 'cause I wanted to be with her so,

'cause I couldn't stand the knowin' that she'd gone a callin' and a

callin' me!"

He was quiet so long that Eli Cronk drew his sleeve across his face to

break the oppressive stillness. Here, in the dead of night, his somber

brother had been transformed into another creature,—a passionate

creature, responding to the call of a dead woman, a man whose hatred

would carry him to fearful lengths.

The hoarse voice broke forth again:

"Midge darlin', dead baby, and all that ye had belongin' to me, I do it

for you! I'll steal his'n, and they'll suffer and suffer—"[Pg 17]

He tossed up his great head with a jerk, crushing the sentiment from his

voice.

"But that don't make no matter now," he muttered. "I'm goin' to take his

kids! He's got two, an' he's prouder'n a turkey cock of 'em. I'll take

'em and I'll make of 'em what I be—I'll make 'em so damn bad that he

won't want 'em no more after I get done with 'em! I'll see what his

woman does when she finds 'em gone! Will ye help, Lem—Eli?"

"Yep, by God, you bet!" burst from both men at once.

"I'll take 'em to the squatter country, up to Mammy's," Lon proceeded,

"and, Eli, if ye'll take one of 'em on the train up to McKinneys Point,

I'll take t'other one up the west side of the lake. I'll pay all the

way, Eli; it won't be nothin' out o' yer pocket. We'll tell Mammy the

kids be mine—see? And ye can have all there be in this here room. Be it

a bargain?"

"Yep," assured Eli, and Lena's consent followed only an instant later.

After that there were no sounds save the snip, snip, snip of the pliers

and the occasional low grating from a jeweled trinket as the steel hook

gouged into the metal.

As Eli Cronk said, Scraggy Peterson left her lonely squatter home two

weeks before with no companion but her vicious black cat. The woman had

intervals of sanity, and during those periods her thoughts turned to a

dark-haired boy, growing up in a luxurious home. In these rare days she

donned her rude clothing, and with the cat perched close to her thin

face walked across the state to Tarrytown. Several times during the five

years after leaving Lem's scow she walked to Tarrytown, returning only

when she had seen the little boy, to take up her squatter life in her

father's hut. So secretive was she that no one had been taken into her

confidence; neither had she interfered with her child in any way. Never

once, hitherto, had her senses left her on those long country marches

toward the east; but often when she turned backward she would utter

forlorn cries, characteristic of her malady.

At eight o'clock, four hours before Lon Cronk opened his heart to his

companions, Scraggy, footsore and weary, entered Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

and seated herself on the damp earth to gather strength. By begging and

stealing she had managed to reach her destination; but now for the first

time on this journey the bats were in her head, sounding the walls of

her poor brain with the ceaseless clatter of their wings. Still the

mother heart called for its own, through the madness—called for one

sight of Lem's child and hers. At length after a long rest she turned

into a broad path which she knew well, and did not halt until she was

staring eager-eyed into the window of Harold Brimbecomb's house which

stood close to the cemetery.

To the left of the Brimbecomb's was the mansion, belonging to the

orphans of Horace Shellington. The young Horace and his sister Ann were

the favorite companions of Everett Brimbecomb, now six years old. He was

a strong, proud, handsome lad. Many conjectures had been made concerning

him by the Tarrytown people, because one day five years before the

delicate, light-haired wife of Mr. Brimbecomb had appeared with a

dark-haired baby boy, announcing that from that day on he would take the

place of her own child who had died a few months before. No person had

told Everett that the millionaire was not his father, nor was he made to

understand that the mother and the home were not his by right of birth.

His bright mind and handsome appearance were the pride of his adopted

mother's life, and his rich father smiled only the more leniently when

the lad showed a rebellious spirit. In the child's dark, limpid eyes

slumbered primeval passions, needing but the dawn of manhood to break

forth, perhaps to destroy the soul beneath their reckless domination.

Everett was entertaining Ann and Horace Shellington at dinner, and after

the repast the youngsters betook themselves to the large square room

given to the young host's own use. Here were multitudinous playthings

and mechanical toys of all descriptions. For many minutes the children

had been too interested to note that the shadows were grown long and

that a somber gloom had settled down over the cemetery that lay just

beyond the windows.

Ann Shellington, a delicate little creature of eight, looked up

nervously. "Everett, draw down the curtain," she said. "It looks so

ghostly out there!"

Ann made a motion toward the window; but the boy did not obey her.[Pg 20]

"Isn't that just like a girl, Horace?" he asked. "I'm not afraid of

ghosts. Dead people can't walk, can they, Horace?"

The other boy answered "No" thoughtfully, as he started a miniature

train across the length of the room.

"Then who is it that walks in the night out there?" insisted the girl.

"Lots of town people have seen it. It's a woman with shaggy hair, and

sometimes her eyes turn green."

"Pouf!" scoffed Everett. "My father says there aren't any such things as

ghosts. I wouldn't be a fraidy cat, Ann."

"I'm not a fraidy cat," pouted the girl. "I always go upstairs alone,

don't I, Horace?"

Another answer in the affirmative, and Horace proceeded to roll the

train back over the carpet.

"If you had any mother," said Everett, "she'd tell you there weren't any

ghosts. My mother tells me that."

"I haven't any mother," sighed the little girl, listlessly folding her

hands in her lap.

"Nor any father, either," supplemented Horace, with seemingly no thought

of the magnitude of his statement. "I don't believe in ghosts, anyhow!"

He glanced up as he spoke, and the train fell with a bang to the floor.

Everett Brimbecomb dropped the toy he held in his hand, and Ann bounded

from her chair. A white face with wide eyes, staring through scraggly

gray hair, appeared at the window. For only an instant it pressed

against the pane, then vanished as if it had never been.

"It was a woman," gasped Horace, "or was it a—"

"It wasn't a ghost," interrupted Everett stoutly. "I dare follow it out

there. Look at me!"

He straightened his shoulders, threw up his dark head, and opened the

door leading to the narrow walk at the[Pg 21] side of the house. In another

moment the watching boy and girl at the window saw him dart into the

hedge and a minute later emerge through it, picking his way among the

ancient graves. Suddenly from behind a tall monument stole a figure, and

as it approached the solemn eyes of the apparition smiled in dull wonder

on Everett Brimbecomb.

Scraggy held out her hands. "Don't run away, little 'un," she whispered.

"There be bats flyin' about in my head; but my cat won't hurt ye."

She passed one arm about the snarling creature perched on her shoulder;

but the cat with a hiss only raised himself higher.

"Don't spit at the pretty boy, Kitty—pretty pussy, black pussy!"

wheedled the woman. "He won't hurt ye, childy. Come nearer, will ye?

This be a good cat."

"Are you a ghost?" demanded Everett, edging into the light.

"Nope, I ain't no ghost. I love ye, pretty boy. Ye won't tell no one

that I speak to ye, will ye? I ain't doin' no hurt."

"What do you carry that cat for, and what's your name?" demanded Everett

insolently; for the proud young eyes had noticed the disheveled figure.

"If any one of our men see you about here, they'll shoot you. I'd shoot

you and your cat, too, if I had my father's gun!"

Scraggy smiled wanly. "Screech Owl's my name," said she. "They call me

that 'cause I'm batty. But ye wouldn't hurt me, little 'un, 'cause I

love ye. How old be ye?"

"Six years old; but it isn't any of your business. Crazy people ought to

be locked up. You'd better go away from here. My father owns that house,

and—don't you follow me through the hedge. Get back, I say! If I call

Malcolm—"[Pg 22]

Everett drew back through the box-hedge, and the boy and the girl at the

window saw the woman squeeze in after him. In another moment the young

heir to the Brimbecomb fortune bounded through the doorway. His face was

white; his eyes were filled with fear.

"Did you see that old woman?" he gasped. "She tried to kiss me, and I

punched her in the face, and her cat did this to my arm."

He pulled up his sleeve, and displayed a long scratch from wrist to

elbow.

"Are you sure it wasn't a ghost, Everett?" asked Ann, shivering.

"Of course, it wasn't," boasted Everett. "It was only a horrid woman

with a cat—that's all."

As he closed the door vehemently, there drifted to the children from the

marble monument and waving trees the faint wail of a night-owl.

On a fashionable street in Syracuse, Floyd Vandecar, district attorney

of the city, lived in a new house, built to please the delicate fancies

of his pretty wife. His career had been comet-like. Graduated from

Cornell University and starting in law with his father, he had succeeded

to a large practice when but a very young man. Then came the call for

his force and strength to be used for the state, and, with a gratified

smile, he accepted the votes of his constituents to act as district

attorney. Then, as Lon Cronk had told, it came within the duty of the

young lawyer to convict the thief of grand larceny committed three years

before. After that Floyd married the lovely Fledra Martindale, and a

year later his twin children were born—a sturdy boy and a tiny girl.

The children were nearly a year old when Fledra Vandecar whispered

another secret to her husband, and Vandecar, lover-like, had gathered

his darling into his arms, as if to hold her against any harm that might

come to her. This happened on the morning following the night when

Silent Lon Cronk told the dark tale of suffering to his pals.

Just how Lon Cronk came to know the inner workings of the Vandecar

household he never confided; but, biding his time, waited for the hour

to come when the blow would be harder to bear. At last it fell, fell not

only upon the brilliant district attorney, but upon his lovely wife and

his hapless children.

One blustering night in March, Lem Crabbe's scow was tied at the locks

near Syracuse. The day for the fulfil[Pg 24]ment of Lon Cronk's revenge had

arrived. That afternoon Lon had come from Ithaca with his brother Eli to

meet Lem.

"Be ye goin' to steal the kids tonight, Lon?" asked Lem.

"Yep, tonight."

"Why don't ye take just one? It'd make 'em sit up and note a bit to

crib, say, the boy."

"We'll take 'em both," replied Lon decisively.

"And if we get caught?" stammered Crabbe.

"We don't get caught," assured Lon darkly, "'cause tonight's the time

for 'em all to be busy 'bout the Vandecar house. I know, I do—no matter

how!"

Wee Mildred Vandecar was ushered into the world during one of the worst

March storms ever known in the western part of New York. As she lay

snuggled in laces in her father's home, a tall man walked down a lane,

four miles from Ithaca, with her sleeping sister in his arms. The dark

baby head was covered by a ragged shawl; two tender, naked feet

protruded from under a coarse skirt. Lon Cronk struggled on against the

wind to a hut in the rocks, opened the door, and stepped inside.

A woman, not unlike him, in spite of added years, rose as he entered.

"So ye comed, Lon," she said.

"Course! Did Eli get here with the other brat?"

"Yep, there 'tis. And he's been squalling for the whole night and day.

He wanted the other little 'un, I'm a thinkin'."

"Yep," answered Lon somberly, "and he wants his mammy, too. But, as I

telled ye before, she's dead."

"Be ye reely goin' to live to hum, Lon?" queried the old woman eagerly.

"Yep. And ye'll get all ye want to eat if ye'll[Pg 25] take care of the kids.

Be ye glad to have me stay to hum?"

"Yep, I'm glad," replied the mother, with a pathetic droop to her

shriveled lips.

Just then the child on the cot turned over and sat up. The small,

tear-stained face was creased with dirt and molasses. Bits of bread

stuck between fingers that gouged into a pair of gray eyes flecked with

brown. Noting strangers, he opened his lips and emitted a forlorn wail.

The other baby, in the man's arms, lifted a bonny dark head with a jerk.

For several seconds the babies eyed each other. Two pairs of brown-shot

eyes, alike in color and size, brightened, and a wide smile spread the

four rosy lips.

"Flea! Flea!" murmured the baby on the bed; and "Flukey!" gurgled the

infant in Lon's arms.

"There!" cried the old woman. "That's what he's been a cryin' for. Set

him on the bed, Lon, for God's sake, so he'll keep his clack shet for a

minute!"

The baby called "Flea" leaned over and rubbed the face of the baby

called "Flukey," who touched the dimpled little hand with his. Then they

both lay down on a rough, low cot in the squatter's home and forgot

their baby troubles in sleep.

The kidnapping of the twins was discovered just after Fledra Vandecar

had presented her husband with another daughter, a tiny human flower

which the strong man took in his hands with tender thanksgiving. The

three days that followed the disappearance of his children were eternal

for Floyd Vandecar. The entire police force of the country had been

called upon to help bring to him his lost treasures. So necessary was it

for him to find them that he neither slept nor worked. He had had to

tell the mother falsehood after falsehood to[Pg 26] keep her content. The

children had suddenly become infected with a contagious disease, and the

doctor had said that the new baby must not be exposed in any

circumstances. After three long weeks of torture it devolved upon him to

tell his wife that her children were gone.

"Sweetheart," he whispered, sitting beside her and taking her hands in

his, "do you love and trust me very much indeed?"

The wondering blue eyes smiled upon him, and small fingers threaded his

black hair.

"I not only love you, Dear, but trust you always. I don't want to seem

obstinate and impatient, Floyd, but if I could see my babies just from

the door I should be happy. And it won't hurt me. I haven't seen them in

three whole weeks."

During the long, agonizing silence the young mother gathered something

of his distress.

"Floyd, look at me!"

Slowly he lifted his white face and looked straight at her.

"Floyd, Floyd, you've tears in your eyes! I didn't mean to hurt you—"

She stopped speaking, and the pain in his heart reached hers.

"Floyd," she cried again, "is there anything the matter with—with—"

"Hush, Fledra darling, little wife, will you be brave for my sake and

for the sake of—her?"

His eyes were still full of tears as he touched the bundle on the bed.

"But my babies!" moaned Mrs. Vandecar. "If there isn't anything the

matter with my babies—"

"I want to speak to you about our children, Dear."

"They are dead?" Mrs. Vandecar asked dully. "My babies are dead?"[Pg 27]

At first Vandecar could scarcely trust himself to speak; but, curbing

his emotion with an effort, he answered, "No, no; but gone for a little

while."

His arms were tightly about her, and time and again he pressed his lips

to hers.

"Gone where?" she demanded.

"Fledra, you must not look that way! Listen to me, and I will tell you

about it. I promise, Fledra. Don't, don't! You must not shake so!

Please! Then you do not trust me to bring them back to you?"

His last appeal brought the tense arms more limply about his neck. She

had believed him absolutely when he said they were not dead.

"Am I to have them tonight?"

"No, dear love."

"Where are they gone?"

"The cradles were empty after little Mildred—"

"They have been gone for—for three weeks!" she wailed. "Floyd, who took

them? Were they kidnapped? Have you had any letters asking for money?"

Vandecar shook his head.

"And no one has come to the house? Tell me, Floyd! I can't bear it!

Someone has taken my babies!"

She raised herself on her arm wildly, fever brightening the anguished

eyes. The husband with bowed head remained praying for them and

especially for her. Another cry from the wounded mother aroused him.

"Floyd, they have been taken for something besides money. Tell me,

Dearest! Don't you know?"

Faithfully he told her that he could think of no human being who would

deal him a blow like this; that he had thought his life over from

beginning to end, but no new truth came out of his mental search.

"Then they want money! Oh, you will pay anything[Pg 28] they demand! Floyd,

will they torture my baby boy and girl? Will they?"

"Fledra, beloved heart," groaned Vandecar, "please don't struggle like

that! You'll be very ill. I promised you that you should have them back

some day soon, very soon. Fledra, sweet wife, you still have the baby

and me—and Katherine."

"I want my little children! I want my boy and girl!" gasped Mrs.

Vandecar. "I will have them, I will! No, I sha'n't lie down till I have

them! I'm going to find them if you won't! I will not listen to you,

Floyd, I won't ... I won't—"

Each time the words came forth they were followed by a moan which tore

the man's heart as it had never been torn before. For a single instant

he drew himself together, forced down the terrible emotion in his

breast, and leaned over his wife.

"Fledra, Fledra, I command you to obey me! Lie down! I am going to bring

you back your babies."

He had never spoken to her in such a tone of authority. She sank under

it with parted lips and swift-coming breath.

"But I want my babies, Floyd!" she whispered. "How can I think of them

out in the cold and the storm, perhaps being tortured—"

"Fledra, sweet love, precious little mother, am I not their father, and

don't you trust me? Wait—wait a moment!"

He moved the babe from her mother's side, called the nurse, and in a low

tone told her to keep the child until he should send for her. Then he

slipped his arms about the wailing mother, lay down beside her, and drew

her to his breast.

During the next few hours of darkness he watched her—watched her until

the night gave way to a shadowy[Pg 29] dawn. And as she slept he still held

her, praying tensely that he might be given power to keep his promise to

her. When she started up he gathered her closer and hushed her to sleep

as a mother does a suffering child. How gladly he would have borne her

larger share, yet more gladly would he have convinced himself that by

morning the children would be again under his roof!

At last Mrs. Vandecar awoke, calmer and with ready faith to acknowledge

that she believed he would accomplish his task. At her own request, he

brought their tiny baby.

"Will you see Katherine, too, Fledra," ventured Vandecar. "The poor

child hasn't slept much, and she can't be persuaded to eat."

Misery, deep and pathetic, flashed in the blue eyes Mrs. Vandecar raised

to his. At length she faltered:

"Floyd, I've never loved Katherine as I should. I'm sorry.... Yes, yes,

I will see her—and you will bring me my babies!"

Vandecar stooped and kissed her; then, with a tightening of his throat,

went out.

Five minutes later a small girl followed Mr. Vandecar in and stood

beside the bed. Fledra Vandecar took the little girl-face in her hands

and kissed it.

The years went on, with the gap still left wide in the Vandecar

household. As month after month passed and nothing was heard of her

children, Mrs. Vandecar gradually gave up hope. Her despair left a

shadow of pathetic pleading in her blue eyes. This constant silent

appeal whitened Floyd Vandecar's hair and caused him to apply himself to

business more assiduously than ever. Never once in all those bitter

years did he connect Lon Cronk with the disappearance of his babies.

Meantime two sturdy children were growing to girlhood and boyhood in the

Cronk hut on Cayuga Lake. So safely had the secret of the kidnapping

been kept from Granny Cronk and the other squatters in the settlement

that the twins were regarded by all as the son and daughter of the

squatter.

The year following Flea's and Flukey's fourteenth birthday the boy was

taken into his foster-father's trade of thieving. At first he was

allowed only to enter the houses and deftly unbar the door for an easier

egress for Eli Cronk and Lem Crabbe. Later he was commanded to snatch up

anything of value he could. Many were the times he wept in boyish

bitterness against the commands of Lon, revealing his sorrows to Flea,

who listened moodily.

"I wouldn't steal nothin' if I was you," she said again and again. But

Flukey one day silenced this reiteration by confiding to her that Pappy

Lon had threatened to turn her to his trade if he rebelled.

One afternoon in late September, Flea left the hut and went out to the

lake. Flukey, Lon Cronk, and Lem Crabbe[Pg 31] had gone to Ithaca to buy

groceries, and it was time for them to return. A chill wind swung the

girl's skirt about her knees, and for some minutes she squatted on the

beach, keeping her eyes upon the lighthouse in the distance.

For the last year Flea had been rapidly growing into a woman. Granny

Cronk had proudly noted that the fair face had grown lovelier, that the

ebony curls fell about her shoulders. The one dream the girl had had was

a dream of long hair, ankle dresses, and girl's shoes. Until that year

Lon had insisted that her hair be kept short, and had himself trimmed

the ebony curls every month. Now, in the damp air, they twisted and

turned in the wildest profusion. The coming of womanhood had thrown new

light into the clear-gray, brown-flecked eyes. At this moment she was

wondering what she and her brother would do if Granny Cronk died. She

shivered as she thought of life in the hut without the protecting old

woman.

Suddenly, from above the Lehigh Valley tracks, she heard the sound of

horses' hoofs. Her attention taken from her meditations, she lifted her

pensive gaze from the lake, wheeled about, and looked for the horseman.

Flea knew that it was not a summer cottager; for many days before the

last of them had taken his family to Ithaca. Perhaps some chance

wayfarer had followed the wrong road. Just below the tracks she caught a

glimpse of a black horse, and as it came nearer Flea noted the rider, a

young man whose kindly dark eyes and white teeth dazzled her. His

straight legs were incased in yellow boots, his fine form in a tightly

fitting riding-coat. Flea had never seen just such a man, not even in

the infrequent visits she made to Ithaca. Something in his smile, as he

drew up his steed and looked down upon her, affected her with a curious

thrill.[Pg 32]

"Little girl, will you tell me if I am on the right road to Glenwood?"

Flea's tongue clove to the roof of her mouth. His voice, cultivated and

deep, made her forget for a moment the question he had asked her. Then

she remembered; but instinctively she did not reply in her usual high

squatter tones.

"Nope, ye got to go back, and turn to the right at the top of the hill.

Ye can't go round the shore from here; the water's too high."

This impulsive desire to choose her words and to modulate her voice came

from a sudden realization that there lived another class of people

outside the squatter settlement of whom she knew little.

"Thank you very much," replied the questioner. "Now I understand that if

I ride to the top of the hill and turn to the right, I'll reach

Glenwood?"

"Yep," answered Flea.

Her embarrassment caused her lips to close over the one word.

Wonderingly she watched the man ride away until the sight of his dark

horse was lost in the trees above the tracks.

"It were a prince," she stammered in a low tone, "a real live prince!"

Flea contemplated the darkening hills with moody eyes. She counted

slowly one by one the towers of the university buildings. This she did

merely from habit; for the expression remained unchanged on her

melancholy face. At length the gray eyes dropped to the water and fixed

their gaze upon a fishing boat turning toward the shore. A few moments

before it had been but a black speck near the lighthouse; but as it came

nearer Flea distinctly saw the two men and the boy in it. Upon the bow

of the boat was perched Snatchet, a yellow terrier, his short ears

perked up with happiness at the prospect of sup[Pg 33]per. When the craft

touched shore the girl rose and ran toward it. Almost in fear, she

searched the face of the youth at the rudder with eyes so like his own

that they seemed rather a reflection than another pair. She said no word

until she took her position beside the boy on the shore, slipping her

hand into his as she walked by his side toward the hut.

"Be ye back for the night, Flukey?" she asked.

"Nope."

"Where ye goin' after supper?"

"To Ithaca."

"Air ye leg a hurtin' ye much?"

"Yep."

"Granny Cronk says as how yer pains be rheumatiz. If ye stay in out of

the night air, ye'll get well."

"Pappy Lon won't let me," sighed Flukey.

He sank down on the cabin threshold, and as he spoke drew a blue trouser

leg slowly up.

"Damn knee!" he groaned. "It gets so twisted! And sometimes I can't

walk."

"Be ye goin' to steal again tonight?" asked the girl, bending toward

him.

"Yep, with Pappy Lon and Lem. I hate it all, I do!" he cried

impetuously.

"What makes ye go? Take a lickin', an' I bet ye'll stay to hum. I

would!"

With a spiteful shake of the black curls, she rubbed a bare toe over

Snatchet's yellow back.

"I wish I was a boy," she went on. "While I hate stealin', I'd do it to

have ye stay to hum, Flukey; then ye'd get well. And—"

She broke off abruptly and lowered her eyes to the shore, where Lem and

Lon were in earnest conversation. At the same moment Lon looked up and

shouted a command:[Pg 34]

"Flea gal, Flea gal, come down here to me!"

Flea dropped the hand of her brother, moved directly to the water's

edge, and stood quietly until Lon chose to speak.

Lem Crabbe's eyes devoured the slight young figure, his smile contorting

the corners of his whiskered mouth. One hand rested on the bow of the

boat, while the long, rusty hook, sharp at the point and thick ironed at

the top, protruded from the other coat-sleeve.

At last Lon Cronk began to speak deliberately, and the girl gave him her

attention.

"Flea, ye be a woman now, ain't ye?" he said "Ye be fifteen this comin'

Saturday."

"Yep, Pappy Lon."

"And yer brother be fifteen on the same day, you bein' twins."

"Yep, Pappy Lon."

"Yer brother's been taken into my trade," proceeded the squatter, "and

it ain't the wust in the world—that of takin' what ye want from them

that have plenty. It's time for ye to be doin' somethin', too. Ye'll go

to Lem's Scow, Flea."

"To Lem's scow?" exclaimed Flea. "That ain't no place for a kid, and

nobody ain't a wantin' me, nuther! I know there ain't!"

"Ain't there nobody a wantin' her in yer scow, Lem Crabbe?" grinned Lon.

"Ye bet there be!" answered Lem, with an evil leer.

Flukey, who had approached the group, placed himself closer to his

sister. "Who—who be wantin' Flea, Lem Crabbe?" he demanded.

"It's me, it's me!" replied Lem, wheeling savagely about.

For a short space of time nothing but the splash of the waves could be

heard as they rolled white on the shore. A change passed over Flea, and

she clutched fiercely at her brother's fingers. It was as if she had

said, "Help me, Flukey, if ye can!" But she did not speak the words;

only stared at the hook-armed man with strained eyes.

"Flea ain't no notion of goin' away right yet, Pappy Lon," burst out

Flukey, catching his breath after the shock. "She's perferrin' to stay

with us; and I'll work for her keep, if ye let her stay."

"Nope, I ain't no notion o' marryin'," repeated Flea, encouraged by her

brother's insistence.

"Who said as how Lem wanted ye to marry him?" sneered Lon, eying her

from head to foot. "Yer notions one way or nother ain't nothin' to me,

my gal. Ye'll go with the man I choose for ye, and that's all there be

to it!"

Dazed by his first words, she whispered, "I hate Lem Crabbe!"

As if by its own volition, the hook rose threateningly to within a short

distance of the fair, appealing face. But it dropped again, as Lon

repeated:

"That ain't nothin' to do with the thing, nuther, Flea. A man ain't a

seekin' for a lovin' woman. He wants her to take care of his shanty and

what he gets by hard work, he does, and he gives her victuals and drink

for the doin' of it. That's enough for you, or for any gal what's a

squatter."

So well did Flea realize the powerlessness of the rigid boy at her side

to help her, that she dropped his hand and alone went nearer to the

thief.

"Can't I stay with you and with Granny Cronk for another year? Can't I

stay? Can't I, Pappy Lon?"

"Nope, I wouldn't keep ye in the shanty if ye had money for yer keeps.

Ye go on a Saturday to Lem's boat to be his woman, ye see?"[Pg 36]

The iron hook by this time was hanging loosely by Lem's side; but a

cruel expression had gathered on the sullen face. A frown drew the

crafty eyes together, bespeaking wrath at the girl's words.

That he would have her at the bidding of her father, Lem never doubted.

During the last three years he had been resolved to take her home in due

time to be his woman. To subdue the proud young spirit, to make her the

mother of children like himself,—the boys destined to be thieves, and

the girls squatter women,—was his one ambition. That he was old enough

to be her father made no difference to him.

He was watching her as she stood in the darkening twilight, gloating

over the thought that his vicious dreams were so near their fulfilment.

Flea was looking into the eyes of her father, and he looked back at her

with an impudent smile.

"Ye don't like the thought of this comin' Saturday, Flea—eh?" he asked

slowly. "But, as I said before, a gal hain't nothin' to do with the

notions of her daddy. And Granny Cronk'll give ye a pork cake to take to

Lem's, and he'll let ye eat it all to yerself. Eh, Lem?"

"Yep," grunted Lem. "She eats the pork cake if she will; but after

that—"

Suddenly Lon silenced Lem's words with a wag of his head toward the

girl. "Flea," he said, "I telled Lem as how ye'd kiss him tonight."

The words stunned the girl, they were so unexpected, so terrible. She

turned her eyes upon Lem and fearfully studied his face. He was gazing

back, his open lips showing his discolored, broken teeth. The coarse,

red hair sprinkled with gray gave a fierce aspect to his whole

appearance, and from the emotion through which he was passing the

muscles under his chin worked to and fro. With a grin he advanced toward

her. Flea fell back[Pg 37] against Flukey. The boy steadied the trembling,

slender body.

"I ain't a goin' to kiss ye," she muttered. "I hate yer kisses! I hate

'em!"

"Ye'll kiss him, jest the same!" ordered Lon.

Closer and closer Lem came toward the girl; then suddenly he sprang at

her like a tiger, crushing the slim figure against his breast. For a

moment Flea was encircled by his left arm. Then she turned fiercely to

the ugly face so close to hers, and in another instant had bitten it

through the cheek. He dropped her with a yelling oath, and Flea sprang

back, turning flashing eyes upon Lon.

"That's how I kiss him afore I go to him," she screamed, "and worser and

worser after he takes me!"

Lon laughed wickedly. He had not expected such a display of spirit. "I

guess ye'll have to wait, Lem," he said; "fer—"

Flea did not hear the rest of the sentence; for she and Flukey were

hurrying toward the hut.

Lem stood wiping the blood from his face. "The cussed spit-cat!" he

hissed. "When I take her in hand—"

"When ye take her in hand, Lem," interrupted Lon darkly, "ye can do what

ye like. Break her spirit! Break her neck, if ye want to! I don't care."

The children found Granny Cronk with bent shoulders and palsied hands

toiling over the supper. About the withered neck hung a red

handkerchief, and on top of the few gray whisps of hair rested a

spotless cap. She grunted as the children entered the room like a

whirlwind and climbed the long ladder to the loft, where for some time

the low voice of Flukey and the sobs of Flea could be heard in the

kitchen below.

It was not until her son had entered and hung his cap upon the peg that

the old woman ventured to speak.[Pg 38]

"Be Flea in a tantrum, Lon?"

"Yep, ye bet she be!"

"Have ye been a beatin' her?"

"Nope, I never teched her," replied the squatter; "but I will beat her,

if she don't do what I tell her. No matter how she kicks ag'in' my

notions, she has to do 'em, Granny!"

"Yep, I know that; but I asked ye what she was a blubberin' about."

"'Cause I says as how on Saturday she's got to go and be Lem's

woman—that's what I says."

"Lem's woman! Do ye mean that she's got to go away?"

"Yep, with Lem Crabbe," replied Cronk; "he's to be her man on her next

birthday. I bet he brings the kid to his likin'!"

"Lem's a bad man, Lon," replied Mrs. Cronk, "and ye be one, too, if ye

be my own son, and Flea's your own flesh and blood, and I like her. It

would be a good thing if ye let her stay to hum while I be a livin'; and

I mean what I say, and I'm yer mammy, and that's the truth!"

"Mammy or no mammy," answered Cronk sullenly, "Flea goes to Lem, and ye

makes her a pork cake, which she can hog down at one gulp, for all I

care—the damn brat! I say it, and Lem says it. He'll dry her tears

after she's left hum, I'm a guessin'!"

Seeing the futility of arguing the question, Mrs. Cronk placed the fish

and beans on his plate and, with a shrill cry to Flea and Flukey, sat

down to eat.

As he stumbled along the rocks to the scow, Lem Crabbe uttered dark

threats against the girl who had bitten him. Her temper and the

spontaneous deed that had marked his face did not lessen his longing to

call her his woman, nor did it take the fever of desire from his veins.

It had[Pg 39] strengthened his passion to such a degree that he now determined

to permit nothing to interfere with his plans. For at least three years

he had lived on the promise of Lon Cronk that he should have the girl

for weal or woe. Six months before he had offered Lon anything within

his power to set the day of Flea's coming to him nearer; but the thief

had shaken his head with the thought that Flea as a girl would not

suffer through indignities as she would as a woman. He felt no remorse

for the other girl that he had ruined so many years back; but he kept

out of the way of the crazy woman who sometimes crossed his path.

Tonight Lem entered the living-room of his boat, muttering an oath that

ended in a groan, dropped the basket on the table, and struck a match.

He was touching it to the candle, when a sound in the corner startled

him. He turned as he finished his task and saw the brilliant eyes of

Scraggy's cat as the animal sat perched on the woman's shoulder. The

presence of Screech Owl surprised him so that he did not move for a

moment, and she spoke first:

"I hain't seed ye in such a long time, Lem, that I thought I'd come and

let ye see my new kitty. He ain't but two years old."

Lem took a long breath. At first he thought that this must be Scraggy's

wraith come to haunt him after some horrible lonely death. He had far

rather deal with a living Scraggy than a dead one, and at once recovered

his composure.

"I hain't sent for ye, have I?" he asked, hanging up his coat. "And if I

ain't sent for ye, then ye needn't be sneakin' round."

"I've a lot to say to ye," sighed Scraggy mournfully, "and I thought as

how the night was better than the day. It's dark now."[Pg 40]

"Then ye'd better trot hum," put in Lem, "if ye don't want another

beatin'."

"I ain't goin' to get no beatin' tonight," assured the woman, throwing

one arm over the bristling cat, "'cause I comed to tell ye somethin'."

Lem turned on her sharply; for Scraggy seemed to speak sanely.

"The bats be gone from my brain, Lem, and I want to tell ye somethin'

'bout Flea—Flea Cronk—and to tell ye that I be hungry."

"What about Flea?" snapped Lem. "Ye're bein' hungry ain't nothin' to do

with me. If ye got somethin' to tell me that I want to hear, lip it out,

and then scoot; for I ain't no time to bother with ye. My time's

precious, Scraggy—see?"

"Yep; but I ain't goin' to tell ye nothin' till ye give me somethin' to

eat."

She cast ravenous eyes on the small bundles Lem was placing on the

table.

"I'll give ye a piece of bread an' 'lasses," was the grudging answer.

"And mind ye, I wouldn't do that but I want to hear what ye say 'bout

Flea."

Avidly the woman ate the thick slice of bread and treacle, offering a

bit now and then to the cat. When she had devoured it Lem spoke:

"Now wash it down with this here water and tell me yer tale—and if ye

lie to me I'll kill ye!"

"I ain't a goin' to lie to ye—I'll tell ye the truth, I will!"

They both drank, the man from the bottle, the woman from a tin cup.

Presently she asked:

"Be ye goin' to marry Flea Cronk?"

"Who's been carryin' tales to ye?" shouted Lem, bounding from his chair.

"Ye better be a mindin' yer[Pg 41] own affairs, or ye'll be havin' nothin' but

bats in yer head till ye die. Scoot for hum! Ye hear?"

"Yep; but I ain't goin' jest yet. Ye want to hear 'bout Flea, don't ye?"

"Yep."

"Then set down an' I'll tell ye."

Lem, growling impatience, seated himself.

"Flea Cronk ain't for you, Lem!"

"Who said as how she ain't?" demanded Lem, starting up. The cat spat

viciously, startled by the sudden movement. "I wish ye'd left that damn

cat to hum! I hain't no notion to be bit by no cat."

"Kitty won't bite ye if ye let me alone—will ye, Kitty? I ain't never

afeard of nothin' when I got him with me—be I, Kitty, pretty pussy?"

"Stop a cooin', ye bughouse woman," snarled Crabbe, "and tell me what ye

got to!"

"I said Flea wasn't for you."

"Ye lie!"

He made a desperate move toward her; but the cat rose threateningly, its

hair standing on end in a mound upon the humped back. Lem fell away with

an oath, and Scraggy, smiling wanly, petted the vicious brute.

"I said ye was to keep away, Lem. Wait till I get done. Flea's got to be

some 'un else's, not yers."

"Who's?" Lem's voice rose; but he did not advance toward her.

"I dunno; but I seed him. He rides a black horse, and has a fine, big

body and wears yeller boots. This afternoon when the day was darkenin' I

saw him from the railroad bed, and I saw Flea's spirit a travelin' with

him. I know that ye cared for her this long time back; but ye can't have

her."

"Who be the feller?" demanded Lem, frowning.[Pg 42]

"I said I didn't know, and I don't."

"Were Flea with him?"

"Nope; not in her body, but jest in her spirit."

"Rats! Scoot along with ye, and take yer cat and get out!"

Scraggy had not noticed the blood oozing from Lem's, cheek until she had

received her dismissal. She passed a long, red, bare arm about the

animal and asked:

"Who bit yer cheek, Lem?"

"Who says it were bit?"

"I say it. I see white teeth a goin' in it. And I see red lips ag'in' it

with deadly hate."

Lem glanced forbiddingly at the woman. "The bats be a comin' again," he

muttered, "and there ain't no tellin' what she'll do. If it wasn't for

that blasted cat, I'd chuck her in the lake!"

But he dared not carry out his threat; for Scraggy was muttering to

herself, the cat rebuffing her rough handling.

In another minute she rose and made toward the steps. Her eyes fell upon

Lem, and sanity flashed back into them.

"I gived the boy to the woman—with golden hair," she stammered, as if

some power were forcing the words from her. "Ye would have killed him.

Yer kid be a livin', Lem!"

Truth rang in her statement, and the man got to his feet abruptly. He

had almost forgotten the black-haired little boy. Only when Scraggy's

name was mentioned to him did he remember. But the woman's words awoke a

new feeling in his heart, and mentally he counted back the years to the

date of his son's birth. Scraggy was still looking at him in

bewilderment, scarcely realizing that her story had been told to the

enemy of her child. She bat[Pg 43]tled with a desire to blurt out the whole

truth; but the man's next words silenced her.

"Who be the golden-haired woman, Scraggy?" he wheedled.

"What woman—what golden-haired woman?"

"The woman who has our brat."

Like lightning a sudden joy filled Scraggy's heart. Her benumbed love

for Lem Crabbe grew mighty in a moment and rushed over her. His words

were softly spoken with an old-time inflection. She sank down with a

cry. She was so near him that the cat rose and spat venomously. Lem's

curses brought Scraggy out of her dreams.

"Chuck that damn cat to the bank," ordered Lem, "if ye want to stay with

me! Do ye hear? Chuck him out!"

"Nope, I ain't a goin' to! I'm goin' hum."

"Not till ye tell me where the boy is. Didn't ye throw him in the

river?"

"Nope."

"What did ye do with him?"

"Gived him away."

"Ye lie! That winder was open, and the river was dark as hell. Ye

throwed him in, I tell ye!"

"Nope; I gived him to a woman—"

She stopped and edged toward the stairs, all her old fear of him

returning. Reaching the short flight, she bounded up, the cat clinging

to her sleeve. Lem did not follow; for the crazy woman had frightened

him. He stood with hushed breath, holding grimly to the wooden table. A

voice from the deck of the scow came down to him.

"I gived him to a rich woman on a yacht. He's rich with mints of money.

Yer kid's a gentleman, Lem Crabbe!"[Pg 44]

He sprang after her to the deck; but nothing greeted him save the cry of

an owl from the ragged rocks and the glistening green of the cat's eyes

as Scraggy hurried away.

After eating his supper, Lon, sullen and moody, looked out upon the

lake, reviewing in his mind the terrible revenge he was soon to

complete. He took his pipe slowly from his pocket and filled it with

coarse tobacco. Soon gray rings lifted themselves to the ceiling and

faded into the rafters. As the smoke curled upward, his mind became busy

with the past, and so vivid was his imagination that outlined in the

smoke rings that floated about him was a girlish face—a face pale and

wan, but a loving, sweet one to him. He could see the fair curls which

clung close to the head; the eyes, serious but kind, seemed to strike

his memory in unforgotten glances. To another than himself the

smoke-formed face would have been plain, perhaps ugly, the weakness of

her race showing in every feature; but not to him. So intent was he with

these thoughts that the present dissolved completely into the past, and

beside him stood a small, fond woman. In his imagination she had risen

from that grave which he had never been able to find in the Potter's

Field. The personality of his dead wife called upon his senses and made

itself as necessary to him then as in the moment of his first rapture

when she had placed her womanly might upon his soul.

His revenge upon Floyd Vandecar would be finished when the gray-eyed

Flea, so like her own father, went away with the one-armed man, to eke

out her destiny amid the squalor of the thief's home.

For months he had been enthralled with the satisfaction of the last act

in the one terrible drama of his life; for[Pg 46] it had played with his rude

fancy as a tigress does with her prey, inflaming his hatred and keeping

alive his desire for retaliation. Flukey was a good thief, although

obeying him at the end of the lash, and Flea would receive her portion

of hate's penalty on her fifteenth birthday.

Cronk did not heed the pitter-patter of his mother's feet as she cleared

the table, nor did he hear the droning of the twin's voices in the loft

above. He was thinking of how the dead woman with her child—his child,

the one small atom he would have loved better than himself—would be

well avenged when Flea went away with Lem.

Lon had kept track of the doings of the young district attorney. He knew

that he had gone to the gubernatorial chair but the year before. The

squatter smiled gloomily as he remembered the words of a newspaper

friendly to Vandecar, in which he had read that Syracuse was full of

painful memories for the new governor, and that Floyd Vandecar had taken

his family down the Hudson, to make another home at Tarrytown, where

Harold Brimbecomb, a youthful friend, resided. Another expression of

dark gratification flitted over Lon's heavy features as he reviewed

again the purport of the article. It had plainly said that in the new

home there would be fewer visions of a lost boy and girl to haunt the

afflicted parents. Lon realized in his savage heart that the change of

scene would not lessen the grief of the stricken family. It was his one

satisfaction to brood over the bereaved father and mother, delighting in

his part of the tragedy and enjoying every evidence of it. Never for a

moment did he think gently of the children, but only of the woman

sacrificed. On this night she stood so close that, with a groan, he put

out his hand. His flesh tingled; for he felt that he could almost touch

her, and his heart clamored for the warmth of the tender body he had

never forgotten.[Pg 47]