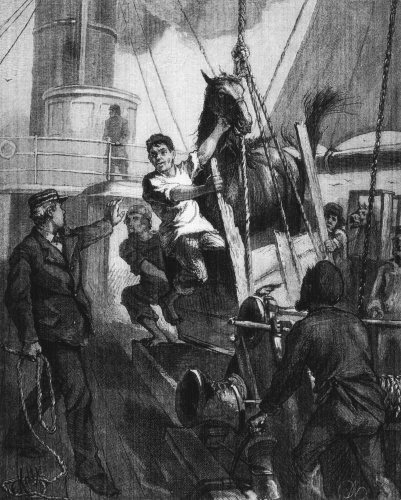

A HORSE AT SEA.

[See page 367.]

Project Gutenberg's St. Nicholas, Vol. 5, No. 5, March, 1878, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: St. Nicholas, Vol. 5, No. 5, March, 1878 Author: Various Release Date: March 15, 2005 [EBook #15374] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ST. NICHOLAS, VOL. 5, NO. 5, *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Lynn Bornath and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net.

A HORSE AT SEA.

[See page 367.]

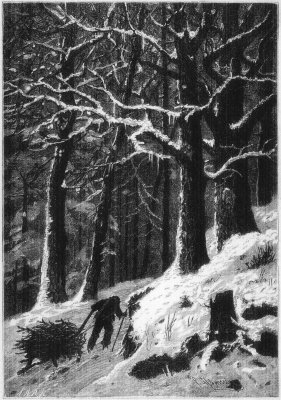

Once upon a time, in a very small village on the borders of one of the great pine forests of Norway, there lived a wood-cutter, named Peder Olsen. He had built himself a little log-house, in which he dwelt with his twin boys, Olaf and Erik, and their little sister Olga.

Merry, happy children were these three, full of life and health, and always ready for a frolic. Even during the long, cold, dark winter months, they were joyous and contented. It was never too cold for these hardy little Norse folk, and the ice and snow which for so many months covered the land, they looked on as sent for their especial enjoyment.

The wood-cutter had made a sledge for the boys, just a rough box on broad, wooden runners, to be sure, but it glided lightly and swiftly over the hard, frozen surface of snow, and the daintiest silver-tipped sledge could not have given them more pleasure.

They shared it, generously, with each other, as brothers should, and gave Olga many a good swift ride; but it was cold work for the little maid, sitting still, and, after a while, she chose rather to watch the boys from the little window, as they took turns in playing "reindeer."

One day they both wanted to be "reindeer" at once, and begged Olga to come and drive, but the chimney corner was bright and warm, and she would not go.

"Of course," said Olaf; "what else could one expect? She is only a girl! I would far rather take Krikel; he is always ready. Hi! Krikel! come take a ride!" and he whistled to the clever little black Spitz dog that Peder Olsen had brought from Tromsöe for the children.

Krikel really seemed to know what was said to him, and scampered to the door, pushed it open with his paws and nose, then, jumping into the little sledge, sat up straight and gave a quick little bark, as if to say: "Come on, then: don't you see I am ready!"

OLAF GIVES KRIKEL A RIDE IN HIS SLED.

"Come, Erik; Krikel is calling us," said Olaf. But Olga was crying because she had vexed her brother, and Erik stayed to comfort her. So Olaf went alone, and he and Krikel had such a good time that they forgot all about everything, till it grew so very dark that only the tracks on the pure, white snow, and a little twinkle of light from the hut window helped them to find their way home again.

In the wood-cutter's home lived some one else whom the children loved dearly. This was old grandmother Ingeborg, who was almost as good as the dear mother who had gone to take their baby sister up to heaven, and had never yet come back to them.

All day long, while the merry children played about the door, or watched their father swing the bright swift ax that fairly made the chips dance, Dame Ingeborg spun and knit and worked in the little hut, that was as clean and bright and cheery as a hut with only one door and a tiny window could be. But then it had such a grand, wide chimney-place, where even in summer great logs and branches of fir and pine blazed brightly, lighting up all the corners of the little room that the sunbeams could not reach.

Here, when tired with play, the children would gather, and throwing themselves down on the soft wolf-skins that lay on the floor before the fire, beg dear grandmother Ingeborg for a story. And such stories as she told them!

So the long winter went peacefully and happily by, and at last all hearts were gladdened at sight of the glorious sun, as he slowly and grandly rose above the snow-topped mountains, bringing to them sunshine and flowers, and the golden summer days.

One bright day in July, father Peder went to the fair in Lyngen.

"Be good, my children," said he, as he kissed them good-bye, "and I will bring you something nice from the fair."

But they were nearly always good, so he really need not have said that.

Now, it was a very wonderful thing indeed for the wood-cutter to go from home in summer, and grandmother Ingeborg was quite disturbed.

"Ah!" said she, "something bad will happen, I know."

But the children comforted her, and ran about so merrily, bringing fresh, fragrant birch-twigs for their beds, shaking out their blankets of reindeer-skins, and helping her so kindly, that the good dame quite forgot to be cross, and before she knew it, was telling them her very, very best story, that she always kept for Sundays.

So the hours went by, and the children almost wearied themselves wondering what father Peder would bring from the fair.

"I should like a little reindeer for my sledge," said Olaf.

"I should like a fur coat and fur boots," said Erik; "I was cold last winter."

You see, these children did not really know anything about toys, so could not wish for them.

"I should like a little sister," said Olga, wistfully. "There are two of you boys for everything, and that is so nice; but there is only one of me, ever, and that is so lonely."

And the little maid sighed; for besides these three, there were no children in the village. The brawny wood-cutters who lived in groups in the huts around, and who came home at night-fall to cook their own suppers and sleep on rude pallets before the fires, were the only other persons whom the little maiden knew; and sometimes the two boys (as boys will do to their sisters) teased and laughed at her, because she was timid, and because her little legs were too short to climb up on the great pile of logs where they loved to play. So it was no wonder that she longed for a playmate like herself.

"Hi!" cried the boys, both together; "one might be sure you would wish for something silly! What should we do with two girls, indeed?"

"But father said he would bring 'something nice,' and I think girls are the very nicest things in the world," replied Olga, sturdily.

There would certainly have been more serious words, but just then good grandmother Ingeborg called "supper," and away scampered the hungry little party to their evening meal of brown bread and cream, to which was added, as a treat that night, a bit of goat's-milk cheese.

During midsummer in Norway the sun does not set for nearly ten weeks, and only when little heads nod, and bright eyes shut and refuse to open, do children know that it is "sleep-time." So on this day, though the little hearts longed to wait for father's coming, six heavy lids said "no," and soon the tired children were sleeping soundly on their sweet, fresh beds of birch-twigs.

A few miles beyond Lyngen, on the north, a little colony of wandering Lapps had pitched their tents, some years before our story begins, and finding there a pleasant resting-place, had made it their home, bringing with them their herds of reindeer to feed on the abundant lichens with which the stony fields and hill-side trees were covered. Somewhat apart from the little cluster of tents stood one, quite pretentious, where dwelt Haakon, the wealthiest Lapp of all the tribe. He counted his reindeer by hundreds, and in his tent, half buried in the ground for safe keeping, were two great chests filled with furs, gay, bright-colored jackets and skirts, beautiful articles of carved bone and wood, and, more valuable than all, a little iron-bound box full of silver marks. For Haakon had married Gunilda, a rich maiden of one of the richest Lapp families, and she had brought these to his tent.

Here, for a while, Gunilda lived a peaceful, happy life. Haakon was kind, and, when baby Niels came to share her love, the days were full of joy and content. She made him a little cradle of green baize bound with bright scarlet, filled with moss as soft and fine as velvet, and covered with a dainty quilt of hare's-skin. This was hung by a cord to one of the tent-poles, and here the baby rocked for hours, while his mother sang to him quaint, weird songs, that yet were not sad because of the joyous baby laugh that mingled with the notes.

But, alas! after a time Haakon fell into bad habits and grew cruel and hard to Gunilda. Though she spoke no word, her meek eyes reproached him when he let the strong drink, or "finkel," steal away his senses; and because he could not bear this look, he gave his wife many an unkind word and blow, so that at last her heart was broken. Even baby Hansa, who had come to take Niels' place in the little cradle, could not comfort her; and, one day, when Haakon was sleeping, stupidly, by the tent-fire, Gunilda kissed her children,—then she, too, slept, but never to waken.

When Haakon came to his senses, he was sad for a while; but he loved his finkel more than either children or wealth, and many a long day he would leave them and go to Lyngen, to drink with his companions there.

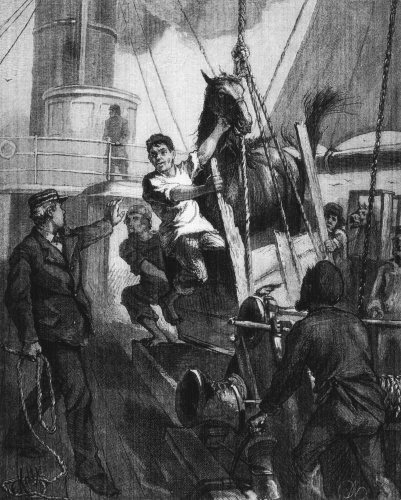

Ah! those were lonely days for Niels and little Hansa. The Lapp women were kind, taking good care of the little ones in Haakon's absence, and would have coaxed them away to their tents to play with the other children; but Niels remembered his gentle-voiced mother, and would not go with those women who spoke so harshly, though their words were kind. Hansa and he were happy alone together. Each season brought its own joys to their simple, childish hearts; but they loved best the soft, balmy summer-time, when the harvests ripened quickly in the warm sunshine, and they could wander away from their tent to the fields where the reapers were at work, who had always a kindly word for the gentle, quiet Lapp children. Here Hansa would sit for hours, weaving garlands of the sweet yellow violets, pink heath, anemones, and dainty harebells, that grew in such profusion along the borders of the fields and among the grain, that the reapers, in cutting the wheat, laid the flowers low before them as well. Niels liked to bind the sheaves, and did his work so deftly that he was always welcome. He it was, too, who made such a wonderful "scarecrow" that not a bird dared venture near. But little Hansa laughed and said: "Silly birds! the old hat cannot harm you. See! I will bring my flowers close beside it." Then the reapers, laughing, called the ugly scarecrow "Hansa's guardian."

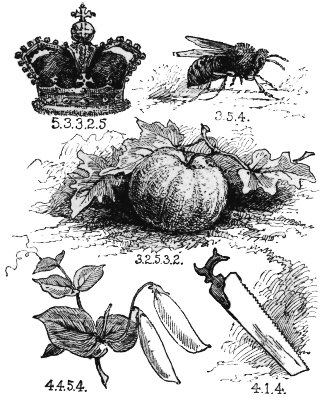

"HANSA'S GUARDIAN."

So the years went by, and the children lived their quiet life, happy with each other. It seemed as though the tender mother-love that had been theirs in their babyhood was around them still, guarding and shielding them from harm. Niels was a wonderful boy, the neighbors said, and little Hansa, by the time she was twelve years old, could spin and weave, and embroider on tanned reindeer-skins (which are used for boots and harness) better than many a Lapp woman. Besides, she was so clever and good that every one loved her. Every one, alas! but Haakon, her father. He was not openly cruel; with Gunilda's death the blows had ceased, but Hansa seemed to look at him with her mother's gentle, reproachful eyes, and so he dreaded and disliked her.

One summer's day he said, suddenly: "Hansa, to-day the great fair in Lyngen is held; dress yourself in your best clothes, and I will take you there."

"Oh, how kind, dear father!" said Hansa, whose tender little heart warmed at even the semblance of a kind word. "That will be joyful! But, may Niels go also? I cannot go without him," she said, entreatingly, as she saw her father's brow darken.

But Haakon said, gruffly: "No, Niels may not go; he must stay at home to guard the tent."

"Never mind, Hansa," whispered Niels; "I shall not be lonely, and you will have so many things to tell me and to show me when you come home, for father will surely buy us something at the fair; and perhaps," he added, bravely, seeing that Hansa still lingered at his side, "perhaps father will love you if you go gladly with him."

"Oh, Niels!" said Hansa, "do you really think so? Quick! help me, then, that I may not keep him waiting."

Never was toilet more speedily made, and soon Hansa stepped shyly up to Haakon, saying gently, "I am ready, father."

She was very pretty as she stood before him, so gayly dressed, and with a real May-day face, all smiles and tears—tears for Niels, to whom for the first time she must say "good-bye," smiles that perhaps might coax her father to love her. But Haakon looked not at her, and only saying "Come, then," walked quickly away.

"Good-bye, my Hansa," said Niels, for the last time. "I love you. Come back ready to tell me of all the beautiful things at the fair."

Then he went into the tent, and Hansa ran on beside her father, who spoke not a word as they walked mile after mile till four were passed, and Lyngen, with its tall church spires, its long rows of houses, and many gayly decorated shops, was before them. Hansa, to whom everything was new and wonderful, gazed curiously about her, and many a question trembled on her tongue but found no voice, as Haakon strode moodily on, till they reached the market-place, and there beside one of the many drinking-booths sat himself down, while Hansa stood timidly behind him. Soon he called for a mug of finkel, and drank it greedily; then another and another followed, till Hansa grew frightened and said, "Oh, dear father, do not drink any more!"

Then Haakon beat her till she cried bitterly.

"Oh, cry on!" said the cruel father, who we must hope hardly knew what he was saying, "for never will I take you back to my tent and to Niels. I brought you here to-day that some one else may have you. You shall be my child no longer. I will give you for a pipe, that I may smoke and drink my finkel in peace. Who'll buy?"

Just then, good Peder Olsen came by, and his kind heart ached for the little maid.

"See!" said he to the angry Lapp. "Give me the child, and I will give you a pipe and these thirty marks as well. They are my year's earnings, but I give them gladly."

"Strike hands! She is yours!" said Haakon, who, without one look at his weeping child, turned away; while the wood cutter led Hansa, all trembling and frightened, toward his home.

At first, she longed to tell her kind protector of Niels, and beg him to take her back. But she was a wise little maid, and curious withal. So she said to herself: "Who knows? It may be a beautiful home, and the kind people may send me back for Niels. I will go on now, for I have never been but one road in all my life, and surely I can find it again."

So she walked quietly on beside father Peder, till at last his little cottage appeared in sight.

"This is your new home, dear child," said he, and they stepped quickly up to the door, opened it softly, and entered the little room.

Grandmother Ingeborg was nodding in her big chair in the chimney corner, but the soft footsteps aroused her, and, looking up, she said:

"Oh! tak fur sidst[A] good Peder. Hi, though! What is that you bring with you?"

Before she could be answered, the children, whose first nap was nearly over, awoke and saw their father with the little girl clinging to his hand, and looking shyly at them from his sheltering arm.

"Oh!" cried Olga, "a little sister! My wish has come true!"—and she ran to the new-comer and gave her sweet kisses of welcome; at which father Peder said, "That is my own good Olga."

But grandmother Ingeborg, who had put on her spectacles, said:

"Ah! I see now! A good-for-nothing Lapp child! She shall not stay here, surely!"

"Listen," said Peder Olsen, "and I will tell you why I brought home the little Hansa, for that is her name,"—and he told the story of the father's drinking so much finkel, and offering to give his little girl for a pipe, and how he himself had purchased her. "But see!" added the worthy Peder, turning toward Hansa, "you are not bound but for as long as the heart says stay."

Hansa looked about, and, meeting Olga's sweet, entreating glance, said, "I will stay ever."

Then Olga cried, joyously, "Now, indeed, have I a sister!" and took her to her own little bed, where soon they both were sleeping, side by side.

As for Olaf and Erik, they were still silent, though now from anger, and that was very bad.

Grandmother Ingeborg, I think, was angry, too, for said she to herself:

"Now I shall have to spin more cloth, and sew and knit, that when her own clothes wear out we may clothe this miserable Lapp child" (for the good dame was a true Norwegian, and despised the Lapps); "and our little ones must divide their brown bread and milk with her, for we are too poor to buy more, and it is very bad altogether. Ah! I was sure something bad would happen,"—and grandmother fairly grumbled herself into bed.

In the morning all were awake early, you may be sure, and gazing curiously at the new-comer, whom they had been almost too sleepy to see perfectly before; and this is how she appeared to their wondering eyes.

She seemed about twelve years old, but no taller than Olga, who was just ten. She had beautiful soft, brown eyes; and fair, flaxen hair, which hung in rich, wavy locks far down her back. She wore a short skirt of dark blue cloth, with yellow stripes around it; a blue apron, embroidered with bright-colored threads; a little scarlet jacket; a jaunty cap, also of scarlet cloth, with a silver tassel; and neat, short boots of tanned reindeer-skin, embroidered with scarlet and white.

Soon grandmother Ingeborg, who had been out milking the cow, came in, and almost dropped her great basin of milk, in her anger.

"What!" cried she to Hansa, "all your Sunday clothes on? That will never do!"

"But I have no others," said the little maid.

"Then you shall have others," said grandmother, and she took from a great chest in the corner an old blue skirt of Olga's, a jacket which Olaf had outgrown, and a pair of Erik's wooden shoes.

Meekly, Hansa donned the strange jacket and skirt; but her tiny feet, accustomed to the soft boots of reindeer-skin, could not endure the hard, clumsy wooden shoes.

"Ah!" said grandmother, who was watching her. "Then must you wear my old cloth slippers," which were better, though they would come off continually.

"Now bring me my big scissors, that I may cut off this troublesome hair," cried Dame Ingeborg. "I do not like that long mane; Olga's head is far neater!"

And, in spite of poor Hansa's entreaties, all her long, beautiful, shining locks were cut short off.

But Hansa proved herself a merry little maid, who, after all, did not care for such trifles. Besides, this, she was so helpful in straining the milk, preparing the breakfast, and bringing fresh twigs for the beds, that Dame Ingeborg quite relented toward her, and said:

"You are very nice indeed—for a Lapp child. If you could only spin, I'd really like to keep you."

Then Hansa moved quickly toward the great spinning-wheel which stood near the open door, and, before a word could be spoken, began to spin so swiftly, yet carefully, that grandmother, in her surprise, forgot to say "Ah," but kissed the clever little maid instead.

"She'll be proud," said the boys, "because she is so wise. Let us go by ourselves and play,"—and away they ran.

"Come," said Olga to Hansa; "though they have run away, they will not be happy without us,"—which wise remark showed that she knew boys pretty well; and the two little maids went hand in hand, and sat down beside the boys.

"We have no room for two girls here," said Olaf, and he gave poor Hansa a very rough push.

"What can you do to make us like you?" said Erik.

"I can tell stories," said Hansa. "Listen!"

And she told them a wonderful tale, far better than grandmother's Sunday best one.

"That is a very good story," said Olaf, when it was finished, "and you are not so bad—for a girl. But still, if my father had not bought you, I should have owned a reindeer for my sledge to-day."

"And I should have had a fur coat and boots, to keep me warm next winter," said Erik.

At this, Hansa opened her bright eyes very wide, and looked curiously at the boys for a moment, then said: "Did you wish for those things?"

"We have wished for them all our lives," said Erik; while Olaf, too sore at his disappointment to say a word, gave Hansa a rude slap instead.

That night, when all were sleeping soundly, little Hansa arose, dressed, and stole softly from the hut. The sun was shining brightly, and it seemed as if the path over which father Peder had led her showed itself, and said, "Come, follow me, and I will lead you home!" And so it did, safely and surely, though the way seemed long, and her little feet ached sorely before she had gone many miles. But she kept bravely on, till at last her father's tent appeared in sight. Then her heart failed her.

"I hope father is not home," said she, "else he will beat me again. I only want my Niels."

And she gave a curious little whistle that Niels had taught her as a signal; but no answer came back. So she crept gently up to the tent, drew aside the scarlet curtain that hung before the opening, and looked in.

Meanwhile, let us go back to Haakon at the fair.

As father Peder led Hansa away, he turned again to the booth, and being soon joined by some friendly Lapps, spent the night, and far on into the next day, in games and wild sports (such as abound at the fair) with them.

At last, a thought of home seemed to come to him, and, heedless of all cries and exclamations from his companions, he hurried away. The long road was passed as in a kind of dream, and, almost ere he knew it, he stood before his tent, with Niels' frightened eyes looking into his, and Niels' eager voice crying:

"Oh, father! where is Hansa? What have you done with my sister?"

"Be silent, boy!" said Haakon, sternly. "Your sister is well, but—she will never come back to the tent again!"

Then, as if suddenly a true knowledge of his crime flashed upon him, he buried his face in his hands, and tears, that for many years had been strangers to his eyes, trickled slowly down his rough brown cheeks, and so, not daring to meet his boy's truthful questioning gaze, he told him all.

"Oh, father, let us go for her! She will surely come back if you are sorry," cried Niels, eagerly.

"You cannot, for, alas! I know neither her new master's name nor whither he went," said Haakon.

Then Niels, in despair, threw himself down on his bed and wept bitterly—wept, till at last, all exhausted with the force of his grief, he slept. How long he knew not, for in the Lapp's tent was nothing to mark the flight of the hours; but he awoke, finally, with a start, sat up and rubbed his eyes, and looked wildly about, saying:

"Yes, there sits father, just where I left him, and there is no one else here. But I am sure I heard Hansa whistle to me; no one else knows our signal, and——Oh! there—there she is at the door!" and he sprang toward her and clasped her in his arms, crying, "Hansa, my Hansa! I have had a dream—such an ugly dream! How joyful that I am awake at last! See, father," he said, leading her to Haakon; "have you, too, dreamed?"

"It was no dream, boy," said his father; and, turning to Hansa, he asked, more gently than he had ever yet spoken to her, "How came you back, my child?"

Then Hansa, clinging closely to Niels the while, told him all that had befallen her, and of the pleasant home she had found, and added, boldly;

"Father, let me take these kind friends some gifts; we have so much, and I wish to make them happy."

"Take what you want, child," said Haakon. "And see! here is a bag of silver marks; give it to Peder Olsen, and say that each year I will fill it anew for him, so that he shall never more want." Then, turning to Niels, he added: "Go you, too, with Hansa. Surely those kind people will give you a home as well. It is better for you both that you have a happier home, and care; and I—can lead my life best alone."

In the wood-cutter's little hut, Olga was the first to discover Hansa's absence.

"Ah, you naughty boys!" cried she. "You have driven my new sister away!"—and she wept all day and would not be comforted.

Bed-time came, but brought no trace of Hansa. Poor, tender-hearted Olga cried herself to sleep; while Olaf and Erik were really both frightened and sorry, and whispered privately to each other, under their reindeer blanket, that if Hansa should ever come back, they would be very good to her.

"And I will give her my Sunday cap," said Erik, "since she cannot wear my shoes."

Two, three, four days went by, and still Hansa came not; and father Peder, who was the last to give up hope, said, finally:

"I fear we shall never see our little maid again."

The children gathered around him, sorrowing, while Dame Ingeborg threw her apron over her head, and rocked to and fro in her big chair in the chimney corner.

Just then came a gentle little tap on the door, which, as Olga sprang toward it, softly opened, and there on the threshold stood little Hansa, smiling at them; and—wonder of wonders!—behind her was a little reindeer, gayly harnessed, with bright silver bells fastened to the collar, which tinkled merrily as it tossed its pretty head. Beside it stood a boy, somewhat taller than Olaf, balancing on his head a great package.

"I have been far, far away to my own home," said Hansa, "and my brother Niels has come back with me, bringing something for you."

Then Niels laid down the package, and gravely opening it, displayed to the wondering eyes real gifts from fairy-land, it seemed.

There were the fur coat and boots, and a cap also, more beautiful than Erik had ever dreamed of. A roll of soft, fine blue wool, for grandmother, came next; then a beautifully embroidered dress, and scarlet apron and jacket, for Olga; and last of all, a fat little leather bag, which Hansa gave to father Peder, saying:

"There are many silver marks for you, and my father has promised that it shall never more be empty, if you will give to Niels and me a home." Then turning quickly to Olaf, she said: "And here is my own pet reindeer 'Friska' for you."

So the children, in the gladness of their hearts, kissed the little maid, and Olaf whispered, "Forgive me that slap, dear Hansa!"

Father Peder stood thoughtfully quiet a moment, then, turning to the children, he said:

"See, little ones! I gave my last mark for Hansa, and knew not where I should find bread for you all afterward; but the dear child has brought only good to us since. I am getting old, and my arms grow too weak to swing the heavy ax, and I thought, often, soon must my little ones go hungry. But now we are rich, and my cares have all gone. So long as they wish, therefore, shall Niels and Hansa be to me as my own children; they shall live here with us, and we will love them well."

Then he kissed all the happy faces, and said: "Now go and play, little ones, for grandmother and I must think quietly over these God-sent gifts."

So the children, first putting Friska, the reindeer, carefully in the little stable beside the cow (so that he should not run away from the strange new home, Hansa said), hastened to their favorite play-place,—a large pine board lying on the slope of the hill, whence they could look far away across the fields and fjords to the Kilpis, the great mountain peaks where, even in summer, the pure white snow lay glistening in the sunlight.

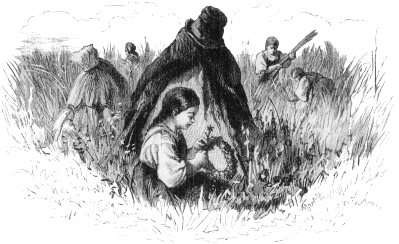

"Ho!" cried Niels, "that is a fine board, but no good so; see what I can do with it!" and lifted one end and put it across a great log that lay near by.

"Now you little fellows," said he to Olaf and Erik, "I am strong as a giant, but I cannot quite roll up this other log alone. Come you and help."

So the boys together rolled the heavy log to its place, and put the other end of the board upon it.

"Now jump!" cried Niels; and with one joyous "halloo" the children were on the broad, springy plank, enjoying to the utmost this novel pleasure.

ON THE SPRING-BOARD.

Their shouts of delight brought the wood-cutter to the door of the little hut, and grandmother Ingeborg following, caught the excitement, and, pulling off her cap, she waved it wildly, crying: "Hurrah for the Lapps! Hurrah!"

Then she and father Peder went back to their chairs in the chimney corner; and Hansa, sitting on the spring-board, with the children around her, told them such a wonderful, beautiful story, that they were quite silent with delight.

At last said Olaf, contentedly, as he lay with his head on Hansa's knee:

"After all, girls are the nicest things in the world!"

"Except boys," said little Hansa, slyly.

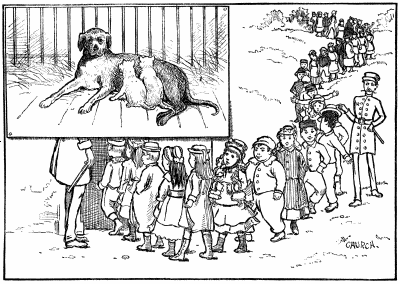

Juno lived in a great park, where there was a menagerie, and neither the park nor the menagerie could have done without Juno. Now, who do you think Juno was? She was a dear old black and brown dog, the best-natured dog in the world. And this was the reason they could not do without her in the park. A lioness died, and left two little lion-cubs with no one to take care of them. The poor little lions curled up in a corner of the cage, and seemed as if they would die. Then the keeper of the menagerie brought Juno, and showed her the little lion-cubs, and said: "Now, Juno, here are some puppies for you; go and take care of them, that's a good dog." Juno's own puppies had just been given away, and she was feeling very badly about it, and was rather glad to take care of the two little lions. They were so pretty, with their soft striped fur and yellow paws, that Juno soon loved them, and she took the best of care of them till they grew old enough to live by themselves. Many people used to come and stand near the big lion's cage, and laugh to see only a quiet old dog, and two little bits of lion-cubs shut in it.

It was very pretty to see Juno playing with the cubs, and all the children who came to the park wanted first to see "the doggie that nursed the lion-puppies." But when they grew large enough they were taken away from her, and sold to different menageries far away, and poor Juno wondered what had become of her pretty adopted children. She looked for them all about the menagerie, and asked all the animals if they had seen her two pretty yellow-striped lion-puppies. No one had seen them, and nearly every one was sorry, and had something kind to say, for Juno was a favorite with many. To be sure, the wolf snarled at her, and said it served her right for thinking that she, a miserable tame dog, could bring up young lions. But Juno knew she had only done as she was told, so she did not mind the wolf. The monkeys cracked jokes, and teased her, saying they guessed she would be given another family to take care of—sea lions, most likely, and she would have to live in the water to keep them in order. This had not occurred to Juno before, and it made her quite uneasy.

"It is not possible they would want me to nurse young sea-lions," said she. "They are so very rude, and so very slippery, I never could make them mind me."

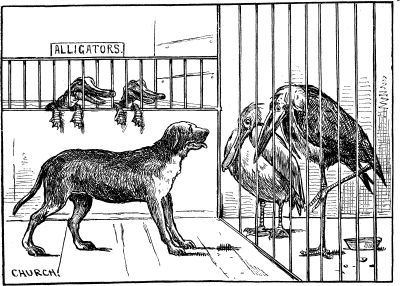

"You may be thankful if you don't get those two young alligators in the other tank," said a gruff-voiced adjutant.

"Good gracious!" exclaimed Juno. "You don't think it possible?"

JUNO IS WARNED BY THE PELICAN.

"Of course it is possible," said a pelican, stretching his neck through his cage-bars. "You'll see what comes of being too obliging."

"We all think you are a good creature, Juno," said a crane. "Indeed, I should willingly trust you with my young crane children, but really, if you will do everything that is asked of you, there's no knowing whose family you may have next."

Juno went and lay down in a sunshiny place near the elephant's house, and thought over all these words. Very soon she grew sleepy, in spite of her anxiety, and was just dropping off into a doze, when she heard the keeper whistle for her. She ran to him and found him in the hippopotamus's cage.

"Juno," said he, "I guess you'll have to take charge of this young hippopotamus, the poor little fellow has lost his mother."

"Dear, dear!" sighed Juno. "I was afraid it would come to this. I'm thankful it isn't the young alligators."

JUNO TAKES CARE OF THE YOUNG HIPPOPOTAMUS.

So Juno took charge of the young hippo,—she called him hippo for short, and only when he was naughty she called him: "Hip-po-pot-a-mus, aren't you ashamed of yourself?" But he was a great trial. He was awkward and clumsy, and not a bit like her graceful little lion-puppies. When he got sick, and she had to give him peppermint, his mouth was so large that she lost the spoon in it, and he swallowed spoon and all, and was very ill afterward. But he grew up at last, and just as Juno had made up her mind not to take care of other people's families any more, the keeper came to her with two young giraffes, and told her she really must be a mother to the poor little scraps of misery, for their mother was gone, and they would die if they weren't cared for immediately. These were a dreadful trouble, and besides, they would keep trotting after her everywhere, till the pelican, and the adjutant, and the cranes nearly killed themselves laughing at her. Poor Juno felt worse and worse, till when one day she heard the keeper say she certainly would have to take care of the young elephant, she felt that she could stand it no longer, and made up her mind to run away. So she said good-bye to all her friends, and ran to the wall of the park. There she gave a great jump, and,—waked up, and found herself in the sunshiny grass near the elephant's house.

"Oh, how glad I am!" said Juno.

"What in the world has been the matter?" asked the elephant. "You've been kicking and growling in your sleep at a great rate. I've been watching you this long time."

"Such dreadful dreams!" said Juno. "Lion-puppies are all very well, but when it comes to hippopotamus, and giraffes, and elephant——"

"What are you talking about?" said the elephant. "I guess you'd better go to your supper; I heard the keeper call you long ago."

So Juno went to her supper very glad to find she had only dreamed her troubles; but she made up her mind that if the old hippopotamus should die, she would run away that very night.

match is a small thing. We seldom pause to think, after it has performed its mission, and we have carelessly thrown it away, that it has a history of its own, and that, like some more pretentious things, its journey from the forest to the match-safe is full of changes. This little bit of white pine lying before me came from far north, in the Hudson Bay Territory, or perhaps from the great silent forests about Lake Superior, and has been rushed and jammed and tossed in its long course through rivers, over cataracts and rapids, and across the great lakes.

We read that near the middle of the seventeenth century it was discovered that phosphorus would ignite a splint of wood dipped in sulphur; but this means of obtaining fire was not in common use until nearly a hundred and fifty years later.

This, then, appears to have been the beginning of match-making. Not that kind which some old gossips are said to indulge in, for that must have had its origin much farther back, but the business of making those little "strike-fires," found in every country store, in their familiar boxes, with red and blue and yellow labels.

The matches of fifty years ago were very clumsy affairs compared with the "parlor" and "safety" matches of to-day, but they were great improvements upon the first in use. Those small sticks, dipped in melted sulphur, and sold in a tin box with a small bottle of oxide of phosphorus, were regarded by our forefathers as signs of "ten-leagued progress." Later, a compound made of chlorate of potash and sulphur was used on the splints. This ignited upon being dipped in sulphuric acid. In 1829 an English chemist discovered that matches on which had been placed chlorate of potash could be ignited by friction. Afterward, at the suggestion of Professor Faraday, saltpeter was substituted for the chlorate, and then the era of friction matches, or matches lighted by rubbing, was fairly begun.

But the match of to-day has a story more interesting than that of the old-fashioned match. As we have said, much of the timber used in the manufacture comes from the immense tracts of forest in the Hudson Bay Territory. It is floated down the water-courses to the lakes, through which it is towed in great log-rafts. These rafts are divided; some parts are pulled through the canals, and some by other means are taken to market. When well through the seasoning process, which occupies from one to two years, the pine is cut up into blocks twice as long as a match, and about eight inches wide by two inches thick. These blocks are passed through a machine which cuts them up into "splints," round or square, of just the thickness of a match, but twice its length. This machine is capable, as we are told, of making about 2,000,000 splints in a day. This number seems immense when compared with the most that could be made in the old way—by hand. The splints are then taken to the "setting" machine, and this rolls them into bundles about eighteen inches in diameter, every splint separated from its neighbors by little spaces, so that there may be no sticking together after the "dipping." In the operation of "setting," a ribbon of coarse stuff about an inch and a half wide, and an eighth of an inch thick, is rolled up, the splints being laid across the ribbon between each two courses, leaving about a quarter of an inch between adjoining splints. From the "setting" machine the bundles go to the "dipping" room.

After the ends of the splints have been pounded down to make them even, the bundles are dipped—both ends—-into the molten sulphur and then into the phosphorus solution, which is spread over a large iron plate. Next they are hung in a frame to dry. When dried they are placed in a machine which, as it unrolls the ribbon, cuts the sticks in two across the middle, thus making two complete matches of each splint.

The match is made. The towering pine which listened to the whisper of the south wind and swayed in the cold northern blast, has been so divided that we can take it bit by bit and lightly twirl it between two fingers. But what it has lost in size it has gained in use. The little flame it carries, and which looks so harmless, flashing into brief existence, has a latent power more terrible than the whirlwind which perhaps sent the tall pine-tree crashing to the ground.

But the story is not yet closed. From the machine which completed the matches they are taken to the "boxers"—mostly girls and women—who place them in little boxes. The speed with which this is done is surprising. With one hand they pick up an empty case and remove the cover, while with the other they seize just a sufficient number of matches, and by a peculiar shuffling motion arrange them evenly, then—'t is done!

The little packages of sleeping fire are taken to another room, where on each one is placed a stamp certifying the payment to the government of one cent revenue tax. Equipped with these passes the boxes are placed in larger ones, and these again in wooden cases, which are to be shipped to all parts of the country, and over seas.

All this trouble over such little things as matches! Yet on these fire-tipped bits of wood millions of people depend for warmth, cooked food and light. They have become a necessity, and the day of flint, steel and tinder seems almost as far away in the past as are the bow and fire-stick of the Indian.

Some idea of the number of matches used in North America during a year may be gained from the fact that it is estimated by competent judges that, on an average, six matches are used every day by each inhabitant; this gives a grand total of 87,400,000,000 matches, without counting those that are exported. Now, this would make a single line, were the matches placed end to end, more than 2,750,000 miles in length! It would take a railroad train almost eight years to go from one end to the other, running forty miles an hour all the time.

How apt to our subject is that almost worn-out Latin phrase, "multum in parvo"—much in little! Much labor, much skill, and much usefulness, all in a little piece of wood scarcely one-eighth of an inch through and about two inches long!

Teddy was such a rogue, you see! If Aunt Ann sent him to the store for raisins, the string on the package would be very loose, and the paper very much lapped over, when he brought it home; if he went to the baker's, the tempting end of the twist loaf was sure to be snapped off in the street, and a dozen buns were never more than ten when they reached the table. Boys are so hungry! Teddy knew every corner of the pantry: if half a pie were left over from dinner, it could not possibly be hidden under any pan, bowl, pail, or cunningly folded towel, but he would find it before supper. Pieces of cake disappeared as if by magic, preserves were found strangely lowered in the crocks, pickles went by the wholesale, gingerbread never could be reckoned on after the first day, and once—only once—did Teddy's mamma succeed in hiding a whole baking of apple tarts in the cellar for a day by setting them under a tub. The cellar never was a safe place again; Aunt Ann tried it with doughnuts, and the crock was empty in two days. She put her stick cinnamon on the top shelf in the closet, behind her medicine bottles, and when she wanted it a week after, there was not a sliver to be found. Then the loaf sugar—I don't know but that was the worst of all. Did he stuff his pockets with it? did he carry it away by the capful? It seemed incredible that anything could go so fast. One day, Aunt Ann detected Teddy behind the window curtain with a tumbler so nearly full of sugar that the water in it only made a thick syrup, and there he was reading "Robinson Crusoe" and sipping this delightful mixture. From that moment Aunt Ann made up her mind that he should "stop it."

"I'll tell him it's nothing more nor less than downright STEALING—so I will," muttered the good soul to herself; "the poor child's never had proper teaching on the subject from one of us; he's got all his pa's appetite without the good principles of our side of the family to save him."

So, the next day, the sugar being out, she bought two dollars' worth while Teddy was at school, and without even telling his mother, she searched the house for a hiding-place. She shook her head at the pantry and cellar, but she visited the garret, and the spare front chamber; she looked into the camphor-chest, she contemplated a barrel of potatoes, she moved about the things in her wardrobe, and at last she hid the sugar! No danger of Teddy finding it this time! Aunt Ann could not repress a smile of triumph as she sat down to her knitting.

Unconscious Teddy came home at noon, ate his dinner, and was off again. His mother and Aunt Ann went out making calls that afternoon, and as Aunt Ann closed the street door she thought to herself—

"I can really take comfort going out, I feel so safe in my mind, now that sugar is hid."

But at tea-time she almost relented when she saw Teddy look into the sugar-bowl, and turn away without taking a single lump.

"He is really honorable," she said to herself; "he thinks that is all there is, and he wont touch it." And she passed the gingerbread to him three times, as a reward of merit.

There was sugar enough in the bowl to sweeten all their tea the next day, and so far all went well. But the third day, in the afternoon, up drove a carry-all to the gate, with Uncle Wright, Aunt Wright, and two stranger young ladies from the city—all come to take tea, have a good time, and drive home again by moonlight.

Teddy's mother sat down in the front room to entertain them, and Aunt Ann hurried out to see about supper. How lucky it was that she had boiled a ham that very morning! Pink slices of ham, with nice biscuit and butter, were not to be despised even by city guests. She had also a golden comb of honey, brought to the house by a countryman a few hours before; it looked really elegant as she set it on the table in a cut-glass dish. Then there were,—oh, moment of suspense! would she find any left?—yes; there were enough sweet crisp seed-cakes to fill a plate.

The table was set—the tea with its fine aroma, and the coffee, amber-clear, were made. The cream was on, so was the sugar-bowl, and Aunt Ann was just going to summon her guests, when she happened to think to lift the sugar-bowl cover and peep in. Sure enough, there wasn't a lump there!

"I must run and fill it!" exclaimed Aunt Ann, lifting it in a hurry, and starting; but she had to stop to think in what direction to go.

"Where was it I put that sugar?" she asked herself.

In the camphor chest? No. In the potatoes? No; she remembered thinking they were not clean enough. Was it anywhere up garret? If she went there and looked around, maybe it would come into her mind. She did go there, sugar-bowl in hand, and she did look around, but all in vain—she could not think where she had put that two dollars' worth of sugar!

And time was flying, the sun was setting—pretty soon the moon would be up. How hungry the company must be, and they must wonder why supper wasn't ready. It would never do to sit down to the table with an empty sugar-bowl, for Aunt Wright always wanted her tea extra sweet, and Uncle Wright never could drink coffee without his eight lumps in the cup. Dear, dear! Aunt Ann was all in a flurry. Why had she ever undertaken to hide that sugar!

"I shall certainly have to send to the store for some more!" she said to herself, "and that will take so long; but it can't be helped."

So she spoke to Teddy, who was sitting in the dining-room window apparently studying his geography lesson, but in reality wondering what in the world Aunt Ann was fluttering all over the house so uneasily for.

"Run to the store, Teddy!" she said quickly; "get me half a dollar's worth of loaf sugar as soon as ever you can."

"Why, Aunt Ann," he replied, "what for? I should think you had sugar enough already."

"So I have!" she exclaimed, nervously. "I got two dollars' worth day before yesterday, and I hid it away in a safe place to keep it from you, and now, to save my life, I can't think where I put it, and I've searched high and low. Hurry!"

Teddy smiled upon her benignly.

"You should have told me sooner what you were looking for," he said. "That sugar is on the upper shelf of your wardrobe, in your muff-box in the farther corner. It is very nice sugar, Aunt Ann!"

"Sure enough!" she cried. "That is where I hid it, and covered it up with my best bonnet and veil. And then, when I went calling, I wore my bonnet and veil, and never once thought about the sugar. I suppose that was when you found it, you bad boy."

"Yes 'm, I found it that time. I was looking for a string," he said; "but I should have found it anyhow in a day or two, even if you hadn't let sugar crumbs fall on the shelf, Aunt Ann!"

"I believe you, you terrible boy!" she rejoined. "Now go call the company to tea."

And she did believe him, and would have given up the struggle from that day, convinced that the fates were against her, but for her heroic resolve to instill straightway into this young gentleman with his pa's appetite the good principles of her side of the family.

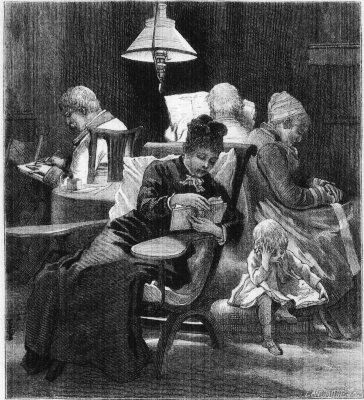

Exactly five minutes before six the party arrived in great state, for Bab and Betty wore their best frocks and hair-ribbons, Ben had a new blue shirt and his shoes on as full-dress, and Sancho's curls were nicely brushed, his frills as white as if just done up.

No one was visible to receive them, but the low table stood in the middle of the walk, with four chairs and a foot-stool around it. A pretty set of green and white china caused the girls to cast admiring looks upon the little cups and plates, while Ben eyed the feast longingly, and Sancho with difficulty restrained himself from repeating his former naughtiness. No wonder the dog sniffed and the children smiled, for there was a noble display of little tarts and cakes, little biscuits and sandwiches, a pretty milk-pitcher shaped like a white calla rising out of its green leaves, and a jolly little tea-kettle singing away over the spirit-lamp as cozily as you please.

"Isn't it perfectly lovely?" whispered Betty, who had never seen anything like it before.

"I just wish Sally could see us now" answered Bab, who had not yet forgiven her enemy.

"Wonder where the boy is," added Ben, feeling as good as any one, but rather doubtful how others might regard him.

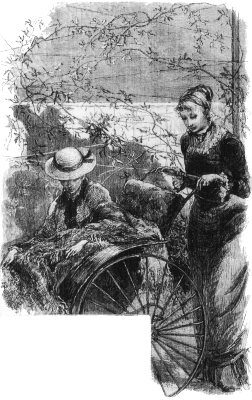

Here a rumbling sound caused the guests to look toward the garden, and in a moment Miss Celia appeared, pushing a wheeled chair in which sat her brother. A gay afghan covered the long legs, a broad-brimmed hat half hid the big eyes, and a discontented expression made the thin face as unattractive as the fretful voice which said, complainingly:

MISS

CELIA

AND

THORNY.

"If they make a noise, I'll go in. Don't see what you asked them for."

"To amuse you, dear. I know they will, if you will only try to like them," whispered the sister, smiling and nodding over the chair-back as she came on, adding aloud: "Such a punctual party! I am all ready, however, and we will sit down at once. This is my brother Thornton, and we are going to be very good friends by and by. Here's the droll dog, Thorny; isn't he nice and curly?"

Now, Ben had heard what the other boy said, and made up his mind that he shouldn't like him; and Thorny had decided beforehand that he wouldn't play with a tramp, even if he could cut capers; so both looked decidedly cool and indifferent when Miss Celia introduced them. But Sancho had better manners, and no foolish pride; he, therefore, set them a good example by approaching the chair, with his tail waving like a flag of truce, and politely presented his ruffled paw for a hearty shake.

Thorny could not resist that appeal, and patted the white head, with a friendly look into the affectionate eyes of the dog, saying to his sister as he did so:

"What a wise old fellow he is! It seems as if he could almost speak, doesn't it?"

"He can. Say 'How do you do,' Sanch," commanded Ben, relenting at once, for he saw admiration in Thorny's face.

"Wow, wow, wow!" remarked Sancho, in a mild and conversational tone, sitting up and touching one paw to his head, as if he saluted by taking off his hat.

Thorny laughed in spite of himself, and Miss Celia, seeing that the ice was broken, wheeled him to his place at the foot of the table. Then seating the little girls on one side, Ben and the dog on the other, took the head herself and told her guests to begin.

Bab and Betty were soon chattering away to their pleasant hostess as freely as if they had known her for months; but the boys were still rather shy, and made Sancho the medium through which they addressed one another. The excellent beast behaved with wonderful propriety, sitting upon his cushion in an attitude of such dignity that it seemed almost a liberty to offer him food. A dish of thick sandwiches had been provided for his especial refreshment, and as Ben from time to time laid one on his plate, he affected entire unconsciousness of it till the word was given, when it vanished at one gulp, and Sancho again appeared absorbed in deep thought.

But having once tasted of this pleasing delicacy, it was very hard to repress his longing for more, and, in spite of all his efforts, his nose would work, his eye kept a keen watch upon that particular dish, and his tail quivered with excitement as it lay like a train over the red cushion. At last, a moment came when temptation proved too strong for him. Ben was listening to something Miss Celia said, a tart lay unguarded upon his plate, Sanch looked at Thorny, who was watching him, Thorny nodded, Sanch gave one wink, bolted the tart, and then gazed pensively up at a sparrow swinging on a twig overhead.

The slyness of the rascal tickled the boy so much that he pushed back his hat, clapped his hands, and burst out laughing as he had not done before for weeks. Every one looked around surprised, and Sancho regarded him with a mildly inquiring air, as if he said, "Why this unseemly mirth, my friend?"

Thorny forgot both sulks and shyness after that, and suddenly began to talk. Ben was flattered by his interest in the dear dog, and opened out so delightfully that he soon charmed the other by his lively tales of circus-life. Then Miss Celia felt relieved, and everything went splendidly, especially the food, for the plates were emptied several times, the little tea-pot ran dry twice, and the hostess was just wondering if she ought to stop her voracious guests, when something occurred which spared her that painful task.

A small boy was suddenly discovered standing in the path behind them, regarding the company with an air of solemn interest. A pretty, well dressed child of six, with dark hair cut short across the brow, a rosy face, a stout pair of legs, left bare by the socks which had slipped down over the dusty little shoes. One end of a wide sash trailed behind him, a straw hat hung at his back, while his right hand firmly grasped a small turtle, and his left a choice collection of sticks. Before Miss Celia could speak, the stranger calmly announced his mission.

"I have come to see the peacocks."

"You shall presently—" began Miss Celia, but got no further, for the child added, coming a step nearer:

"And the wabbits."

"Yes, but first wont you—"

"And the curly dog," continued the small voice, as another step brought the resolute young personage nearer.

"There he is."

A pause, a long look, then a new demand with the same solemn tone, the same advance.

"I wish to hear the donkey bray."

"Certainly, if he will."

"And the peacocks scream."

"Anything more, sir?"

Having reached the table by this time, the insatiable infant surveyed its ravaged surface, then pointed a fat little finger at the last cake, left for manners, and said, commandingly;

"I will have some of that."

"Help yourself; and sit upon the step to eat it, while you tell me whose boy you are," said Miss Celia, much amused at his proceedings.

Deliberately putting down his sticks, the child took the cake, and, composing himself upon the step, answered with his rosy mouth full:

"I am papa's boy. He makes a paper. I help him a great deal."

"What is his name?"

"Mr. Barlow. We live in Springfield," volunteered the new guest, unbending a trifle, thanks to the charms of the cake.

"Have you a mamma, dear?"

"She takes naps. I go to walk then."

"Without leave, I suspect. Have you no brothers or sisters to go with you?" asked Miss Celia, wondering where the little runaway belonged.

"I have two brothers, Thomas Merton Barlow and Harry Sanford Barlow. I am Alfred Tennyson Barlow. We don't have any girls in our house, only Bridget."

ALFRED TENNYSON BARLOW.

"Don't you go to school?"

"The boys do. I don't learn any Greeks and Latins yet. I dig, and read to mamma, and make poetrys for her."

"Couldn't you make some for me? I'm very fond of poetrys," proposed Miss Celia, seeing that this prattle amused the children.

"I guess I couldn't make any now; I made some coming along. I will say it to you."

And, crossing his short legs, the inspired babe half said, half sung the following poem:[B]

"That's all of that one. I made another one when I digged after the turtle. I will say that. It is a very pretty one," observed the poet with charming candor, and, taking a long breath, he tuned his little lyre afresh:

"Bless the baby! where did he get all that?" exclaimed Miss Celia, amazed, while the children giggled as Tennyson, Jr., took a bite at the turtle instead of the half-eaten cake, and then, to prevent further mistakes, crammed the unhappy creature into a diminutive pocket in the most business-like way imaginable.

"It comes out of my head. I make lots of them," began the imperturbable one, yielding more and more to the social influences of the hour.

"Here are the peacocks coming to be fed," interrupted Bab, as the handsome birds appeared with their splendid plumage glittering in the sun.

Young Barlow rose to admire, but his thirst for knowledge was not yet quenched, and he was about to request a song from Juno and Jupiter, when old Jack, pining for society, put his head over the garden wall with a tremendous bray.

This unexpected sound startled the inquiring stranger half out of his wits; for a moment the stout legs staggered and the solemn countenance lost its composure, as he whispered, with an astonished air:

"Is that the way peacocks scream?"

The children were in fits of laughter, and Miss Celia could hardly make herself heard as she answered, merrily:

"No, dear; that is the donkey asking you to come and see him. Will you go?"

"I guess I couldn't stop now. Mamma might want me."

And, without another word, the discomfited poet precipitately retired, leaving his cherished sticks behind him.

Ben ran after the child to see that he came to no harm, and presently returned to report that Alfred had been met by a servant and gone away chanting a new verse of his poem, in which peacocks, donkeys, and "the flowers of life" were sweetly mingled.

"Now I'll show you my toys, and we'll have a little play before it gets too late for Thorny to stay with us," said Miss Celia, as Randa carried away the tea-things and brought back a large tray full of picture-books, dissected maps, puzzles, games, and several pretty models of animals, the whole crowned with a large doll dressed as a baby.

At sight of that, Betty stretched out her arms to receive it with a cry of delight. Bab seized the games, and Ben was lost in admiration of the little Arab chief prancing on the white horse, "all saddled and bridled and fit for the fight." Thorny poked about to find a certain curious puzzle which he could put together without a mistake after long study. Even Sancho found something to interest him, and standing on his hind-legs thrust his head between the boys to paw at several red and blue letters on square blocks.

"He looks as if he knew them," said Thorny, amused at the dog's eager whine and scratch.

"He does. Spell your name, Sanch," and Ben put all the gay letters down upon the flags with a chirrup which set the dog's tail to wagging as he waited till the alphabet was spread before him. Then with great deliberation he pushed the letters about till he had picked out six; these he arranged with nose and paw till the word "Sancho" lay before him correctly spelt.

"Isn't that clever? Can he do any more?" cried Thorny, delighted.

"Lots; that's the way he gets his livin' and mine too," answered Ben, and proudly put his poodle through his well-learned lessons with such success that even Miss Celia was surprised.

"He has been carefully trained. Do you know how it was done?" she asked, when Sancho lay down to rest and be caressed by the children.

"No 'm, father did it when I was a little chap, and never told me how. I used to help teach him to dance, and that was easy enough, he is so smart. Father said the middle of the night was the best time to give him his lessons, it was so still then and nothing disturbed Sanch and made him forget. I can't do half the tricks, but I'm going to learn when father comes back. He'd rather have me show off Sanch than ride, till I'm older."

"I have a charming book about animals, and in it an interesting account of some trained poodles who could do the most wonderful things. Would you like to hear it while you put your maps and puzzles together?" asked Miss Celia, glad to keep her brother interested in their four-footed guest at least.

"Yes 'm, yes 'm," answered the children, and fetching the book she read the pretty account, shortening and simplifying it here and there to suit her hearers.

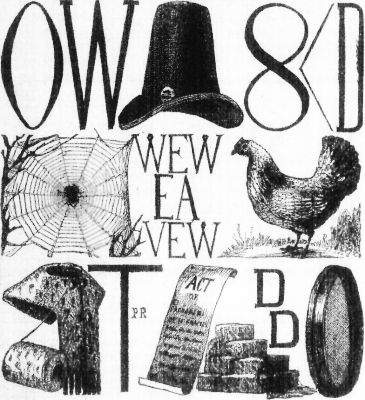

"'I invited the two dogs to dine and spend the evening, and they came with their master, who was a Frenchman. He had been a teacher in a deaf and dumb school, and thought he would try the same plan with dogs. He had also been a conjurer, and now was supported by Blanche and her daughter Lyda. These dogs behaved at dinner just like other dogs, but when I gave Blanche a bit of cheese and asked if she knew the word for it, her master said she could spell it. So a table was arranged with a lamp on it, and round the table were laid the letters of the alphabet painted on cards. Blanche sat in the middle waiting till her master told her to spell cheese, which she at once did in French, F R O M A G E. Then she translated a word for us very cleverly. Some one wrote pferd, the German for horse, on a slate. Blanche looked at it and pretended to read it, putting by the slate with her paw when she had done. "Now give us the French for that word," said the man, and she instantly brought C H E V A L. "Now, as you are at an Englishman's house, give it to us in English," and she brought me H O R S E. Then we spelt some words wrong and she corrected them with wonderful accuracy. But she did not seem to like it, and whined and growled and looked so worried that she was allowed to go and rest and eat cakes in a corner.

"'Then Lyda took her place on the table, and did sums on a slate with a set of figures. Also mental arithmetic which was very pretty. "Now, Lyda," said her master, "I want to see if you understand division. Suppose you had ten bits of sugar and you met ten Prussian dogs, how many lumps would you, a French dog, give to each of the Prussians?" Lyda very decidedly replied to this with a cipher. "But, suppose you divided your sugar with me, how many lumps would you give me?" Lyda took up the figure five and politely presented it to her master.'"

"Wasn't she smart? Sanch can't do that," exclaimed Ben, forced to own that the French doggie beat his cherished pet.

"He is not too old to learn. Shall I go on?" asked Miss Celia, seeing that the boys liked it though Betty was absorbed with the doll and Bab deep in a puzzle.

"Oh yes! What else did they do?"

"'They played a game of dominoes together, sitting in chairs opposite each other, and touched the dominoes that were wanted; but the man placed them and kept telling how the game went, Lyda was beaten and hid under the sofa, evidently feeling very badly about it. Blanche was then surrounded with playing-cards, while her master held another pack and told us to choose a card; then he asked her what one had been chosen, and she always took up the right one in her teeth. I was asked to go into another room, put a light on the floor with cards round it, and leave the doors nearly shut. Then the man begged some one to whisper in the dog's ear what card she was to bring, and she went at once and fetched it, thus showing that she understood their names. Lyda did many tricks with the numbers, so curious that no dog could possibly understand them, yet what the secret sign was I could not discover, but suppose it must have been in the tones of the master's voice, for he certainly made none with either head or hands.'

"It took an hour a day for eighteen months to educate a dog enough to appear in public, and (as you say, Ben) the night was the best time to give the lessons. Soon after this visit the master died, and these wonderful dogs were sold because their mistress did not know how to exhibit them."

"Wouldn't I have liked to see 'em and find out how they were taught. Sanch, you'll have to study up lively for I'm not going to have you beaten by French dogs," said Ben, shaking his finger so sternly that Sancho groveled at his feet and put both paws over his eyes in the most abject manner.

"Is there a picture of those smart little poodles?" asked Ben, eying the book, which Miss Celia left open before her.

"Not of them, but of other interesting creatures; also anecdotes about horses, which will please you, I know," and she turned the pages for him, neither guessing how much good Mr. Hamerton's charming "Chapters on Animals" were to do the boy when he needed comfort for a sorrow which was very near.

"Thank you, ma'am, that's a tip-top book, 'specially the pictures. But I can't bear to see these poor fellows," and Ben brooded over the fine etching of the dead and dying horses on a battle-field, one past all further pain, the other helpless but lifting his head from his dead master to neigh a farewell to the comrades who go galloping away in a cloud of dust.

"They ought to stop for him, some of 'em," muttered Ben, hastily turning back to the cheerful picture of the three happy horses in the field, standing knee-deep among the grass as they prepare to drink at the wide stream.

"Aint that black one a beauty? Seems as if I could see his mane blow in the wind, and hear him whinny to that small feller trotting down to see if he can't get over and be sociable. How I'd like to take a rousin' run round that meadow on the whole lot of 'em," and Ben swayed about in his chair as if he was already doing it in imagination.

"You may take a turn round my field on Lita any day. She would like it, and Thorny's saddle will be here next week," said Miss Celia, pleased to see that the boy appreciated the fine pictures, and felt such hearty sympathy with the noble animals whom she dearly loved herself.

"Needn't wait for that. I'd rather ride bare-back. Oh, I say, is this the book you told about where the horses talked?" asked Ben, suddenly recollecting the speech he had puzzled over ever since he heard it.

"No, I brought the book, but in the hurry of my tea-party forgot to unpack it. I'll hunt it up to-night. Remind me, Thorny."

"There, now, I've forgotten something too! Squire sent you a letter, and I'm having such a jolly time I never thought of it."

Ben rummaged out the note with remorseful haste, protesting that he was in no hurry for Mr. Gulliver, and very glad to save him for another day.

Leaving the young folks busy with their games, Miss Celia sat in the porch to read her letters, for there were two, and as she read her face grew so sober, then so sad, that if any one had been looking he would have wondered what bad news had chased away the sunshine so suddenly. No one did look, no one saw how pitifully her eyes rested on Ben's happy face when the letters were put away, and no one minded the new gentleness in her manner as she came back to the table. But Ben thought there never was so sweet a lady as the one who leaned over him to show him how the dissected map went together, and never smiled at his mistakes.

So kind, so very kind was she to them all that when, after an hour of merry play, she took her brother in to bed, the three who remained fell to praising her enthusiastically as they put things to rights before taking leave.

"She's like the good fairies in the books, and has all sorts of nice, pretty things in her house," said Betty, enjoying a last hug of the fascinating doll whose lids would shut so that it was a pleasure to sing "Bye, sweet baby, bye," with no staring eyes to spoil the illusion.

"What heaps she knows! More than Teacher, I do believe, and she doesn't mind how many questions we ask. I like folks that will tell me things," added Bab, whose inquisitive mind was always hungry.

"I like that boy first-rate, and I guess he likes me, though I didn't know where Nantucket ought to go. He wants me to teach him to ride when he's on his pins again, and Miss Celia says I may. She knows how to make folks feel good, don't she?" and Ben gratefully surveyed the Arab chief, now his own, though the best of all the collection.

"Wont we have splendid times? She says we may come over every night and play with her and Thorny."

"And she's going to have the seats in the porch lift up so we can put our things in there all dry, and have 'em handy."

"And I'm going to be her boy, and stay here all the time; I guess the letter I brought was a recommend from the Squire."

"Yes, Ben: and if I had not already made up my mind to keep you before, I certainly would now, my boy."

Something in Miss Celia's voice, as she said the last two words with her hand on Ben's shoulder, made him look up quickly and turn red with pleasure, wondering what the Squire had written about him.

"Mother must have some of the 'party,' so you shall take her these, Bab, and Betty may carry baby home for the night. She is so nicely asleep, it is a pity to wake her. Good-bye till to-morrow, little neighbors," continued Miss Celia, and dismissed the girls with a kiss.

"Isn't Ben coming, too?" asked Bab, as Betty trotted off in a silent rapture with the big darling bobbing over her shoulder.

"Not yet; I've several things to settle with my new man. Tell mother he will come by and by."

Off rushed Bab with the plateful of goodies; and, drawing Ben down beside her on the wide step, Miss Celia took out the letters, with a shadow creeping over her face as softly as the twilight was stealing over the world, while the dew fell and everything grew still and dim.

"Ben, dear, I've something to tell you," she began, slowly, and the boy waited with a happy face, for no one had called him so since 'Melia died.

"The Squire has heard about your father, and this is the letter Mr. Smithers sends."

"Hooray! where is he, please?" cried Ben, wishing she would hurry up, for Miss Celia did not even offer him the letter, but sat looking down at Sancho on the lower step, as if she wanted him to come and help her.

"He went after the mustangs, and sent some home, but could not come himself."

"Went further on? I s'pose. Yes, he said he might go as far as California, and if he did he'd send for me. I'd like to go there; it's a real splendid place, they say."

"He has gone further away than that, to a lovelier country than California, I hope." And Miss Celia's eyes turned to the deep sky, where early stars were shining.

"Didn't he send for me? Where's he gone? When's he coming back?" asked Ben, quickly, for there was a quiver in her voice, the meaning of which he felt before he understood.

Miss Celia put her arms about him, and answered very tenderly:

"Ben, dear, if I were to tell you that he was never coming back, could you bear it?"

"I guess I could—but you don't mean it? Oh, ma'am, he isn't dead?" cried Ben, with a cry that made her heart ache, and Sancho leap up with a bark.

"My poor little boy, I wish I could say no."

There was no need of any more words, no need of tears or kind arms round him. He knew he was an orphan now, and turned instinctively to the old friend who loved him best. Throwing himself down beside his dog, Ben clung about the curly neck, sobbing bitterly:

"Oh, Sanch, he's never coming back again; never, never any more!"

Poor Sancho could only whine and lick away the tears that wet the half-hidden face, questioning the new friend meantime with eyes so full of dumb love and sympathy and sorrow that they seemed almost human. Wiping away her own tears, Miss Celia stooped to pat the white head, and to stroke the black one lying so near it that the dog's breast was the boy's pillow. Presently the sobbing ceased, and Ben whispered, without looking up:

"Tell me all about it; I'll be good."

Then, as kindly as she could, Miss Celia read the brief letter which told the hard news bluntly, for Mr. Smithers was obliged to confess that he had known the truth months before, and never told the boy lest he should be unfitted for the work they gave him. Of Ben Brown the elder's death there was little to tell, except that he was killed in some wild place at the West, and a stranger wrote the fact to the only person whose name was found in Ben's pocket-book. Mr. Smithers offered to take the boy back and "do well by him," averring that the father wished his son to remain where he left him, and follow the profession to which he was trained.

"Will you go, Ben?" asked Miss Celia, hoping to distract his mind from his grief by speaking of other things.

"No, no; I'd rather tramp and starve. He's awful hard to me and Sanch, and he'll be worse now father's gone. Don't send me back! Let me stay here; folks are good to me; there's nowhere else to go." And the head Ben had lifted up with a desperate sort of look went down again on Sancho's breast as if there was no other refuge left.

"You shall stay here, and no one shall take you away against your will. I called you 'my boy' in play, now you shall be my boy in earnest; this shall be your home, and Thorny your brother. We are orphans, too, and we will stand by one another till a stronger friend comes to help us," cried Miss Celia, with such a mixture of resolution and tenderness in her voice that Ben felt comforted at once, and thanked her by laying his cheek against the pretty slipper that rested on the step beside him, as if he had no words in which to swear loyalty to the gentle mistress whom he meant henceforth to serve with grateful fidelity.

Sancho felt that he must follow suit, and gravely put his paw upon her knee, with a low whine, as if he said: "Count me in, and let me help to pay my master's debt if I can."

Miss Celia shook the offered paw cordially, and the good creature crouched at her feet like a small lion bound to guard her and her house forever more.

"Don't lie on that cold stone, Ben; come here and let me try to comfort you," she said, stooping to wipe away the great drops that kept rolling down the brown cheek half hidden in her dress.

But Ben put his arm over his face, and sobbed out with a fresh burst of grief:

"You can't; you didn't know him! Oh, daddy! daddy!—if I'd only seen you jest once more!"

No one could grant that wish; but Miss Celia did comfort him, for presently the sound of music floated out from the parlor—music so soft, so sweet, that involuntarily the boy stopped his crying to listen; then quieter tears dropped slowly, seeming to soothe his pain as they fell, while the sense of loneliness passed away, and it grew possible to wait till it was time to go to father in that far-off country lovelier than golden California.

How long she played Miss Celia never minded, but when she stole out to see if Ben had gone she found that other friends, even kinder than herself, had taken the boy into their gentle keeping. The wind had sung a lullaby among the rustling lilacs, the moon's mild face looked through the leafy arch to kiss the heavy eyelids, and faithful Sancho still kept guard beside his little master, who, with his head pillowed on his arm, lay fast asleep, dreaming, happily, that "Daddy had come home again."

A TALK OVER THE HARD TIMES.

I believe that the youngsters in our family consider my study a very pleasant room. There are some books, pictures, and hunting implements in it, and I have quite a large number of curious things stored in little mahogany cabinets, including a variety of specimens of natural history and articles of savage warfare, which have been given to me by sailors and travelers. In one of these cabinets there are the silver wings of a flying-fish, the poisoned arrows of South Sea cannibals, sharks' and alligators' teeth, fragments of well-remembered wrecks, and an inch or two of thick tarred rope.

The latter appears to be a common and useless object at the first glance, but when examined closely it is not so uninteresting. It measures one and one-eighth of an inch in diameter, and running through the center are seven bright copper wires, surrounded by a hard, dark brown substance, the nature of which you do not immediately recognize. It is gutta-percha, the wonderful vegetable juice, which is as firm as a rock while it is cold and as soft as dough when it is exposed to heat. This is inclosed within several strands of Manilla hemp, with ten iron wires woven among them. The hemp is saturated with tar to resist water, and the wires are galvanized to prevent rust. You may judge, then, how strong and durable the rope is, but I am not sure that you can guess its use.

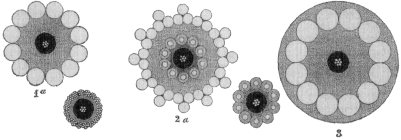

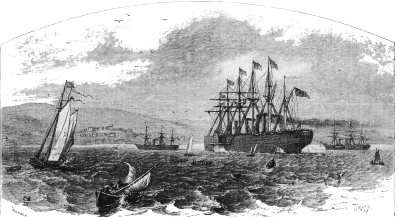

Near the southern extremity of the western coast of Ireland there is a little harbor called Valentia, as you will see by referring to a map. It faces the Atlantic Ocean, and the nearest point on the opposite shore is a sheltered bay prettily named Heart's Content, in Newfoundland. The waters between are the stormiest in the world, wrathy with hurricanes and cyclones, and seldom smooth even in the calm months of midsummer. The distance across is nearly two thousand miles, and the depth gradually increases to a maximum of three miles. Between these two points of land—Valentia in Ireland and Heart's Content in Newfoundland—a magical rope is laid, binding America to Europe with a firm bond, and enabling people in London to send instantaneous messages to those in New York. It is the first successful Atlantic cable, and my piece was cut from it before it was laid. Fig. 2 on the next page shows how a section of it looks, and Fig. 3 shows a section of the shore ends, which are larger.

SECTIONS OF CABLES (REDUCED). 1. Main cable of 1858. 1a. Shore end, abandoned cable of 1858. 2. Main cable of 1866. 2a. Shore-end, recovered cable of 1865. 3. Shore end of cable of 1866.

Copper is one of the best conductors of electricity known, and hence the wires in the center are made of that metal. Water, too, is an excellent conductor, and if the wires were not closely protected, the electricity would pass from them into the sea, instead of carrying its message the whole length of the line. Therefore, the wires must be encased or insulated in some material that will not admit water and is not itself a conductor. Gutta-percha meets these needs, and the hemp and galvanized wire are added for the strength and protection they afford to the whole.